Plateaus of Positivity

A new documentary and CD highlight the soulful genius of Virginia Beach’s own Justin Kauflin.

By Tom Robotham

If you watch only one new documentary this year, let me tell you—without reservation—it should be Keep On Keepin’ On.

The gorgeous, lovingly crafted film tells the story of the relationship between jazz pianist Justin Kauflin of Virginia Beach and the legendary trumpet player and master teacher Clark Terry.

It’s a must, of course, for jazz fans. It’s also a must for anyone in the field of education, for it conveys important lessons about what it means—or can mean—to be a teacher. But most important, it is a deeply moving source of inspiration for anyone who’s facing hardships and feeling discouraged.

Lord knows, both Kauflin and Terry have faced their own hardships. Kauflin, who was born in 1986, went blind at the age of 11 from a degenerative eye disease. Terry, who was born in 1920, lived a blessed life for many decades. He is revered by his peers and idolized by young musicians. But for 60 years, he has lived with diabetes, and several years ago it began to take its toll. He finally had to have both feet amputated—and lost his sight.

The beauty of the film is that it displays the full range of emotions both Kauflin and Terry have experienced. In one of the most moving moments of the documentary, the night before Terry is scheduled to undergo the double amputation, he admits to his wife Gwen that he’s scared. “I don’t think I can make it through this task,” he says.

He did make it through, thanks to the love and support of family and friends and an attitude he embraced long ago. “Challenges are a part of life, as you know,” he tells Kauflin at one point. “But your mind is a powerful asset. Use it for positive thoughts, and you’ll learn what I’ve learned. I call it, getting on the plateau of positivity.”

Kauflin was wide open to this advice. He was always a happy child, his mother observes in the film. And his blindness never got the best of him. Indeed, at one point, after discovering jazz, he told his mother that he wished something bad would happen to him so he could play like the jazz masters.

“What do you mean?” she replies. “You lost your sight. That’s kinda bad.”

“No, not really,” he responds. “Not like these guys. They went through some really bad times.”

On the other hand, in spite of Terry’s advice, Kauflin sometimes feels that his mind is his “biggest enemy.” He felt this way, in particular, after learning that he’d been selected as a semi-finalist for the prestigious Thelonious Monk International Jazz Competition. “I psyche myself out,” he laments.

Nerves did get the best of him during that showcase performance, and though he performed beautifully by most standards, he implies that he thinks this may have been the reason he was not chosen as a finalist. But afterward, Terry kept Kauflin’s spirits up. Although their student-teacher relationship could well have ended when Kauflin graduated from Paterson in 2008, Kauflin continued to make regular trips to visit Terry at his home in Little Rock, Arkansas. It was there a couple of years ago that Kauflin met the great Quincy Jones. Terry had taken Jones under his wing when Jones was just a boy—and became so impressed with Jones’ development that he eventually left the Duke Ellington Orchestra to join Jones’ own band. Jones never forgot what Terry did for him, and has embraced the idea of paying it forward. Impressed upon hearing Kauflin play, he offered to take the young pianist on a world tour—then produce his next album. “I can’t get his sound out of my head,” Jones told Terry after first meeting Kauflin. “Together we have to let the world know about him.”

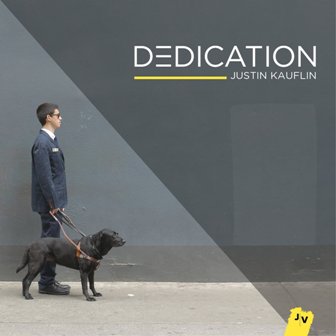

THE ALBUM IS NOW FINISHED and will be released this week. The title, Dedication, has a double meaning. It reflects Kauflin’s unwavering commitment to music; but it also refers to paying tribute. All of the songs are originals, and seven out of the 12 tracks are dedications to individuals who’ve been important to him. They include Norfolk-based jazz drummer and composer Jae Sinnett, who taught and mentored Kauflin when the young pianist was attending The Governor’s School for the Arts; Norfolk-based pianist and educator John Toomey, and Liz Barnes, one of his early piano teachers.

And of course, there is a piece dedicated to Terry, titled simply “For Clark.” To my mind it is the most moving piece on the album, although I’ll admit that there might be a double bias on my part. For one thing, having just watched the documentary for a second time, I can’t get this hugely inspiring story out of my mind. Moreover, I’m partial to pieces that are slow and tenderly lyrical. “For Clark” begins that way, with lush, singing piano tones floating over gentle drum brushes. The tempo picks up in the song’s midsection, as does the intensity of Kauflin’s playing, with more percussive chord clusters, before settling down again into the balladic lyricism of the opening. It is a wonderful evocation of their relationship, which has been filled with great love, tenderness and seriousness, but also punctuated by many moments of playfulness.

“The Professor,” dedicated to the late pianist and teacher Mulgrew Miller, who died last year, is another favorite of mine because of its light bouncing rhythm and the degree to which it showcases Kauflin’s astonishing dexterity on the keyboard.

Given that dexterity, it would be tempting for some pianists to simply show off their chops. There’s an abundance of virtuosic displays on this album, but Kauflin, even as a teenager (I first saw him perform when he was at the Governor’s School), always had more maturity than that—maturity and soul. Some of that comes from his religious devotion, and three tracks on the album, in fact, were inspired by his Catholicism. The importance of religion also comes through clearly in the lovely “Mother’s Song,” which is dedicated to his mom, and to Barnes, whom he regards as a kind of mother figure. In its opening chord progression, at least, it is strongly reminiscent of a church hymn.

Taken together, the tracks on Dedication mark another important step in Kauflin’s effort to find his own voice as an artist. “My sound is something that troubles me,” he says at one point in the documentary. “I have to figure out how to be me.”

The importance of this goal became more evident to him under Terry’s tutelage, since Terry’s music is instantly recognizable to anyone in the know. “He’d play a couple of notes and right away you’d say, ‘That’s Clark Terry,’” observes the trumpet player Arturo Sandoval.

Kauflin has now found a distinctive voice, both as a pianist and a composer, and that’s due as well to the choice of musicians with whom he chooses to collaborate—on this album, drummer Billy Williams, bassist Chris Smith, and guitarist Matt Stevens. I especially like the interplay here between Kauflin and Stevens, and the sonic colors and textures that emerge from it.

What comes through, in the end, is Kauflin’s deep humanity and love—his love for God, his love for his family, his love of music, of course, and perhaps, above all, his love for Terry—surely one of the most inspiring and generous jazz musicians in history. As vocalist Diane Reeves puts it in the film, “That life force of his—everybody should take a lesson [from that].” In time, I have no doubt, people will be saying the same thing about Kauflin.