(“Sade,” Anthony Burks, Sr)

By Betsy DiJulio

Delayed for two years due to the global pandemic, Soul Finger Project was worth the wait.

Conceived by Ramel Jasir, (FL) the show brings together for the first time his work and that of three friends: Anthony Burks, Sr. (FL), Arthur Rogers (NC), and Clayton Singleton (VA). Though I spoke with Gallery Supervisor Stephen Grunnet in advance of my visit to the Portsmouth Art & Cultural Center and had seen photos from the opening online, I was not prepared for the glory that is this show.

Grunnet called it a “visual anti-depressant,” but I still was not prepared for the exuberant song sung by these large, commanding paintings. Other patrons were in the gallery during my Thursday afternoon visit, and we all kept exclaiming to each other, our jaws in a permanent drop.

(“Rare,” Arthur Rogers Jr.)

The show, which draws on influences from contemporary Black culture, North African roots, and the Caribbean, occupies both the upstairs and downstairs galleries. While I have long felt the upstairs space, with its gleaming black polished floors, elevates any work shown there—though the work never needs elevating—the saturated colors, strong patterns, and assertive presences in these paintings sing out not only from the walls, but from their reflections on the floor. A palpable energy pulsates from this work, apparently channeling that of the makers. Says Grunnet, “All these guys run circles around me…they are super-energetic and passionate.”

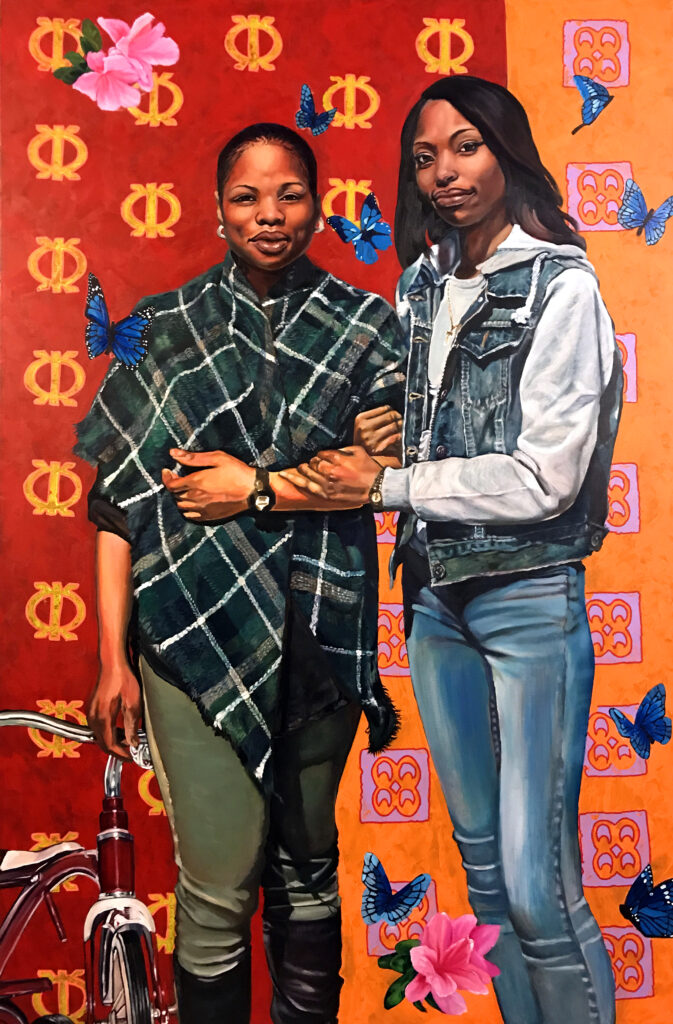

Much has been written about Singleton, especially of late, including by me, and with good reason. He is the senior statesman—though not so “senior”—and sonorous voice for the transformative power of art in the realm of social justice and the need for a quickening evolution of race relations. His is a profound and prolific presence in the regional art scene and has been for a good long time. Filled with North African Adinkra symbols, among others, patterns, and metaphorical objects, his lush figurative paintings are about ideas that matter, elevating people and building community. Frequently using his friends and family members as subjects, Singleton’s work is nonetheless universal, rife with resonant themes.

(“Two Sisters,” Clayton Singleton)

The new-to-me artist in this show who I can’t stop thinking about is Anthony Burks, Sr. His mixed-media pieces have a no less impactful, though quieter, presence. In his large-scale work, he includes portraits, most often rendered in black-and-white profiles against clean white backgrounds, adorned with colorful insects and accessories: hats, headscarves, jewelry, and hair combs. In his richly earth-toned Rooted Ground series, trees grow from exaggeratedly high horizon lines, their roots reaching far down to morph into stunning portraits of insects and animals like elephants, rhinos, and zebras.

Jasir creates similarly large, but syncopated and dazzling, non-objective compositions in palettes that are, at times, jewel-toned and, at others, earthy and more subdued. Some of the paintings appear to be poured acrylic while others are painstakingly painted patterns. For one body of the latter, he has developed a laborious technique for creating a meticulous, raised, tone-on-tone surface. This relief texture, in and of itself, is captivating with a mod vibe.

Rogers’ large contributions to the joyous celebration are figurative portraits of Caribbean Carnival-goers with flamboyant body adornment. Considered somewhat raucous and hedonistic, this long heterogeneous cultural tradition is a complex mash-up of influences from Catholicism and Colonialism, but also emancipation and liberation. In Rogers depictions, one can almost hear the music and feel the sweat of dancers in masquerade.

(The paintings of Ramel Jasir are dazzling)

The show is, as always, exquisitely installed. Curator, Gayle Paul, not only creates visual reverberations through echoing forms and colors in adjacent works, but establishes sly pairings of repeated images or gestures that sneak up on you. An example of the latter includes a Singleton painting of vocalizing children hung across from a Burks painting of a zebra either barking, braying, or snorting, his intention—alertness, curiosity, impatience, or anger—unclear.

In sum, reflects Gunnet, “It is such a positive exhibition…exactly what this community needs right now.” As humanity seems, in so many sectors, to be circling the drain faster and faster, I would have to agree.

WANT TO SEE?

Soul Finger Project

Through June 12

Portsmouth Art & Cultural Center