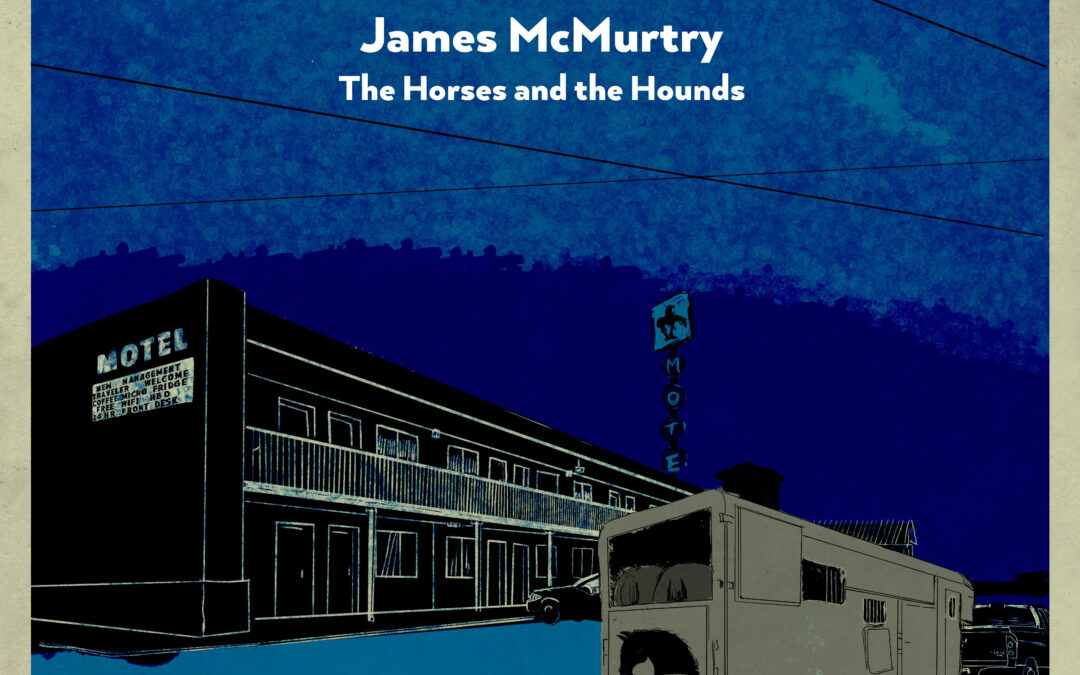

(James McMurtry is back on the road in support of “The Horses and the Hounds.” Photo by Mary Keating Bruton.)

By Jim Morrison

It’s the details that make James McMurtry’s songs compelling character studies. That and the melodies, of course.

There are the parents strapping their kids in the car, giving them a little vodka in cherry Coke for the drive to a family reunion in Oklahoma. There’s Uncle Slayton with his Asian bride and Airstream trailer who still makes whiskey but cooks up meth because his moonshine doesn’t sell. He plays high-stakes bingo every Friday.

There’s Roscoe from East St. Louis, who didn’t quite miss the guy who ran a stoplight at the Shawnee bypass. And there’s Bob from down by Lake Texoma who coached the AA football champions for two years running and is stopping at a mom and pop gun shop to buy an SKS rifle and some steel-core ammo produced by an East bloc country that no longer needs them.

Those characters are from just one McMurtry composition, “Choctaw Bingo,” an eight-minute epic. It’s an unflinching portrait of life out there in the middle, about people who may get out, but never get beyond.

The story is an anthem for our aggrieved times. Except that McMurtry released it on his 2002 album, “Saint Mary of the Woods” and then issued a blistering live version on his 2004 disc with the Heartless Bastards, “Live in Aught-Three.”

The people in “Choctaw Bingo” are characters you imagine him finding as he travels the country, navigating four lanes day after day. He makes albums, he says, when the crowds start to thin. Shows pay the bills. It’s the reverse of touring to promote album sales in a time of earning fractions of pennies per streaming play.

What does he see out there these days? “More of the same,” he says during a call from Texas. “Angry people coast to coast.”

Over the years, he’s had a knack for chronicling the stories told over a Main Street lunch counter in places exemplified by some of his titles — “Forgotten Coast,” “Pocatello,” “Levelland,” and “Talkin’ at the Texaco.”

He writes about people nostalgic for a past that wasn’t as good as they remember. His love songs — and there are plenty if you listen closely — are haltingly honest about the ties that rub raw, which, if you think about it, is romantic. His narrators are often white men who grew up hard and have no choice but to slip into the shady side here or there to provide for their family.

Stephen King says McMurtry “may be the truest, fiercest songwriter of his generation.” In 2017, The New York Times Magazine pronounced “Copper Canteen” one of 25 songs “that tell us where music is going.” The venerable critic Robert Christgau called “We Can’t Make It Here Anymore,” released in 2004, the song of the decade.

Should I hate a people for the shade of their skin

Or the shape of their eyes or the shape I’m in

Should I hate ’em for having our jobs today

No, I hate the men sent the jobs away

I can see them all now, they haunt my dreams

All lily-white and squeaky clean

They’ve never known want, they’ll never know need

Their shit don’t stink and their kids won’t bleed

Their kids won’t bleed in the damn little war

And we can’t make it here anymore

Despite the portrait, McMurtry demurs when asked about writing political songs. His songs are character-driven, not slogan-driven.

“The problem if you try to put forth a political perspective is that you run the risk of writing a sermon,” he says. “Because the song doesn’t have its head. It starts to get didactic and you start forcing things. If you follow the song where it wants to go, you get a better song. You just have to decide what you are. Are you a songwriter or an activist? Some people can be both. Steve Earle can do it.”

“I try to write the best song I can,” he adds. “So I got real lucky with ‘We Can’t Make It Here’ because that was the way I was feeling at the time. And the characters agreed with me.”

He writes plenty of songs that don’t match his views. Take “Carlisle’s Haul’ from his latest, 2014’s “Complicated Game,” inspired by watermen going out on the mouth of the Potomac under cover of night, fishing limits be damned. “I’ve never had to make a living as a commercial fisherman,” McMurtry says. “So, you know, the narrator probably doesn’t agree with me. I think you gotta manage fisheries so we’ll still have them. But if I had to pull my living out of the water, I might cheat.”

For McMurtry, songs start with a couple of lines and a melody. “I’m thinking, Okay, who said that? And then I try to envision the character that would have said that,” he says. “Sometimes I can kind of work backwards into the story if I can get a verse-chorus structure.”

He doesn’t romanticize writing. “It’s mechanical as much as anything else,” he says. “A song is not poetry. It’s not prose. It’s to be sung. So you have to write it in such a way that you can sing it. And that can change the whole idea of the song. That can change the character for the sake of a better line that has more impact.”

The songs arrive in minutes or years. Take two cuts off of “Complicated Game.”

“Ain’t Got a Place” arrived after the album had been completed, sung into his iPhone in his room at the Royal Street Inn. “That song took me less time to write than anything I’ve ever written. I’d flown to New Orleans to listen to some mixes so that we wouldn’t be emailing stuff back and forth,” he says. “The computer crashed and so I didn’t get the work done. I was kind of pissed off and kind of drunk that night and sat up in my room over the R bar and I started playing with opposites. It’s all just wordplay. River runs east out of West Virginia. River runs west out of Tennessee. East west. Up down. North south. And then there’s another song there, “You Got to Me” that took about 15 years to write piecemeal. That’s why there are some very dated details. It’s been a long time since we’ve had hard subway tokens.”

McMurtry has just released his first album in seven years. He will play several new songs from “The Horses and the Hounds,” including the lead track “Canola Fields,” when he performs as part of the North Shore Point House Concerts and Virginia Arts Festival show on April 15 at the Perry Pavilion.

McMurtry left Austin three years ago and moved 30 miles away to Lockhart, another of a long line of refugees from a town that’s not as weird as it once was and is a whole lot more expensive. “Musicians can’t live there anymore. It’s insane,” he says. “The whole state of California moved there.”

He’s not sentimental about the songwriting community in Austin. “It’s more like a place we just all wound up,” he says of Austin. “One of my ex-bass players used to say Austin’s a great place to leave your stuff. It’s a good place to tour out of because you can get to either coast and back in three and a half weeks, do a pretty good job and still have a life.”

He grew up in Virginia with his mother, Jo Scott McMurtry, who taught English at the University of Richmond for about three decades, and his stepdad. He was nine when he fell for songwriting. Until then, he says, “I didn’t put any thought to where songs came from.” That changed after a couple of shows, first Johnny Cash, Carl Perkins, the Statler Brothers, and the Carter Family at the Richmond Coliseum.

“The next one was Kris Kristofferson at the Mosque. They now changed the name to some cigarette company. I played there with Jason Isbell not too long ago. Kristofferson and Rita Coolidge right before the “Jesus Was a Capricorn” record came out.”

“Those guys seemed to be having such a great time,” he says. “That’s when I decided that’s what I wanted to do.”

WANT TO GO?

James McMurtry

Co-presented by Virginia Arts Festival/North Shore Point House Concerts

April 15

Perry Pavilion