By Tom Robotham

When I was a young reporter for The Staten Island Advance in the early ‘80s, I looked to a lot of older journalists for inspiration. But chief among them was Nat Hentoff, whose columns in The Village Voice never failed to enlighten me and renew my desire to touch the hearts and minds of my own readers.

On January 8, when I awoke to the news that he had died, I found myself reflecting on just how big an impact he’d had on my life and work—first as a writer whom I admired, and later as a personal mentor and friend.

What struck me first and foremost about Hentoff’s columns, back in those early years of my career, was his passion—his fierce devotion to social justice. He made that clear, especially, in his writing about education, and when I became chief education reporter for the Advance I tried to emulate him. In my spare time, I was also immersing myself in New York City’s jazz culture, and Hentoff’s books on the subject—especially the lyrical and impressionistic Jazz Is—made me want to write about that as well. I began writing record reviews for the Advance, and in 1982 my editor gave me a weekly music column.

Especially vivid in my memory was the night I met and interviewed Dizzy Gillespie at the Blue Note. As he approached my table after his last set, he noticed the book I had with me—Hentoff’s The Jazz Life.

“That’s a great book,” Gillespie said. “Nat has done so much for this music.” Gillespie was not unusual in this respect. Musicians often regard music journalists with skepticism, but Hentoff was beloved by the jazz world.

Over the next two decades I continued to read Hentoff’s work as often as I could, and in 1998, when I became editor of Port Folio Weekly here in Norfolk, one of my first decisions was to pick up Nat’s syndicated column. But his influence on my work extended far beyond that. I remained committed, in particular, to covering jazz, even though market research did not warrant it. Hentoff’s writing had taught me that the best journalists write about subjects they think are important, not simply about what will drive readership.

Around this time I learned that Frank Foster—longtime member of the Count Basie Orchestra, and director after Basie died—had moved to the Norfolk area a few years earlier. In 2001, shortly after Foster suffered a stroke, I asked for an interview so I could do a story on his career and his rehabilitation efforts. When the story was published, I decided to mail a copy to Hentoff. I didn’t expect to hear from him but figured it couldn’t hurt.

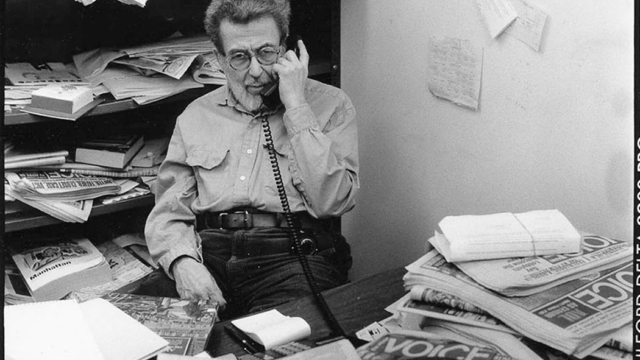

One night, about a week later, as I was getting ready to leave my office, my phone rang. It was Hentoff. He told me not only that he liked my piece on Foster but that he admired what I was doing with the publication as a whole and asked to be put on the subscription list. I readily agreed, needless to say, though I assumed he was just being polite.

As it turned out, his interest was authentic. Every few weeks after that, he called to comment on one thing or another that he’d seen in my paper. In the course of those conversations, which ranged far and wide, he taught me a great deal more about jazz, and his other major area of expertise—the Bill of Rights.

In late autumn of 2003, when I learned that then-Attorney General John Ashcroft was planning a visit to Norfolk, I assigned one of my writers to cover the speech. In preparation, she asked if there were any specific questions she should ask him. I offered a few thoughts, then suggested she call Nat for advice.

After hanging up the phone and telling me how helpful he’d been, she said, “Oh, by the way—Nat told me to tell you that he quoted you in his upcoming Jazz Times column.”

When the column came out in the Jan-Feb. 2004 issue of the magazine, I was both thrilled and humbled. He hadn’t just quoted me—he’d devoted his entire column to Port Folio Weekly and our commitment to jazz coverage.

I share that fact with some reluctance, for fear it sounds like bragging. But to me, this moment illustrates one of Hentoff’s most striking qualities: his profound generosity and willingness to help younger journalists however he could. And for me, needless to say, it was profoundly gratifying. Here was a man I’d admired from afar for more than two decades, and now he had become a personal mentor.

After that Nat and I continued to talk on the phone periodically. But one conversation stands out in my mind above all. In that week’s issue, I’d quoted him in my weekly column, and he’d called to thank me.

“Sometimes,” he said, “you wonder if anyone’s listening.”

Again I was taken aback. Nat was a journalist, after all, who was widely regarded and respected as one of the nation’s leading experts on the First Amendment, not to mention the first non-musician to receive a Jazz Masters Award from the National Endowment for the Arts. Indeed, his awards and professional achievements are too numerous to name. And yet even he wondered at times if anyone was paying attention to his work.

Yes, Nat—I was listening. Always. So were countless other readers. The legacy you left is immeasurable. And the impact you had on me was incalculable. For that, I express my deepest gratitude.