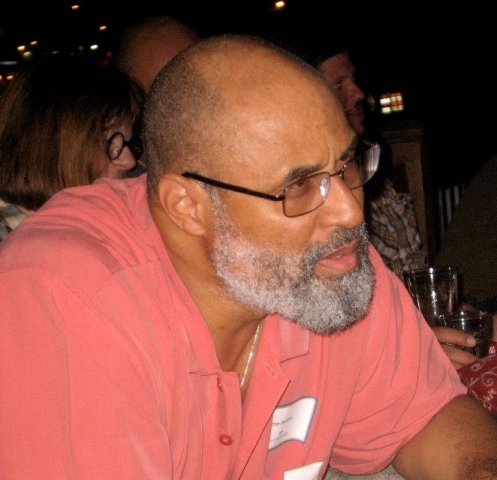

By Tom Robotham

Tim Seibles is nationally acclaimed poet and a professor of creative writing and literature at Old Dominion University. Over the years he has won many accolades, notably in 2012, when he was a finalist for the National Book Award.

This year he was named Virginia’s Poet Laureate. Recently I sat down with Seibles to talk about that honor, his newest work, and other topics that he and I have discussed many times as friends over the years.

First of all, congratulations on your appointment as Virginia’s Poet Laureate. How do you feel about that?

Well, it’s always nice to be noticed. As much time as poets, and most writers, spend in solitude with nobody knowing how much we claw our faces over a phrase or a word, it’s nice to have some public recognition. So in that respect being poet laureate is a lovely thing.

Now it’s a matter of thinking about what I can do with it beyond giving a lot of readings, which I hope to do. I would like to try and figure out a way to use it as a bully pulpit for poetry in general, and to maybe draw some attention to local poets—Virginia poets—other than myself.

You’ve written a lot of poetry about race. Do you think that was maybe one consideration in selecting you, given everything that’s going on in the country right now?

You know, maybe. Given the world we live in, if you’re a black person or a brown person, it’s hard to imagine that race doesn’t figure in in any way. But again, I have no evidence of that, and I don’t know who the other candidates were. But yeah, I think in light of the current discourse on race that maybe—maybe—the governor thought that it would be valuable to appoint a black poet.

Not that one can do a hell of a lot about racial problems as a poet laureate. But you can give voice to certain concerns that might otherwise go unvoiced.

When you noted that there’s only so much you can do as poet laureate, my immediate thought was, there’s only so much you can do as a poet in general. Do you ever get discouraged and start to wonder if you’re speaking into a vacuum?

Of course there are those moments. I mean, you also write. There must be moments when you think, what’s the point? Even today, there was that report about a young man who was shot in the back by police. But it’s not that I think that anything we do as writers is supposed to be an instant corrective. I’m not an idiot. [laughs.] It’s not as if I think the police are going to read one of my poems and say, wait a minute? What did Seibles say? Let’s rethink our whole policy. But sometimes it does feel like you’re this very small insect shouting at an elephant.

The thing is, it’s never been the largest mass of people who move and shake the culture. What you’re really trying to do is create an important dynamic, or to add to a heightened discourse about what’s going on in society, and that you may reach some of the people who really do have the potential to affect a particular situation. You and I have said this about teaching, too—you don’t know who’s really listening. And so I think you write poems with this blind faith that it really matters that someone tries to use language eloquently and piercingly. I mean, I think about the poets that I’ve read, and their value to me—how they make me see differently and think differently. And so I hope that maybe I’m part of this chain of people who use language in such a way as to enliven the cultural discourse.

This reminds me of comments I see on Facebook from time to time saying, you’re an idiot if you think you’re going to change anybody’s mind with your posts—as if the only reason to write something is to change people’s minds. But I remember you once said to me, when I wondered whether my writing is just preaching to the choir, that the choir needs preaching to.

Yeah, the choir needs to hear the song, too. Certainly someone who’s an archconservative or an overt racist, or someone who does not appreciate thinking very much, is not going to be affected by anything I do. But there are many people who are wrestling with difficult issues and want someone to help them clarify what’s happening around us. I think good poetry can be a part of that, just as good journalism can, or good song lyrics. And so you hope that when you’ve done good work—when you’ve really written your ass off—that someone reads it and says, of course! How come I have never said this or thought this? But mostly I think what happens is, people perhaps add some flavoring of your work to an already active body of thinking, and it just helps them along the path of being aware, or attentive to their own biases. That’s all you can hope for—you want people to think, and hopefully feel. Because when a thought is accompanied by emotion it has greater sticking power. That’s why we love beautiful music, or art of any kind.

Last time I spoke to you about this, you weren’t really clear on what being poet laureate would entail. Do you have any more information? Are you going to be required to write poems on demand, for example, for special occasions?

No, apparently not. I also don’t have a budget, which is unfortunate, because I’d like to have some readings around the state, where you could have local poets come out and read to people. We have great people all over the state who are writing poetry or engaging in spoken word, and I would like to make that more evident during my tenure as poet laureate. I may do it out of my own pocket because I want to be active in this position.

You and I both encounter people who are intimidated by poetry. Their response is, I don’t understand it; I don’t know what it means. What do you say to people like that?

I was talking about this not long ago, actually. Most of the time it’s because their encounters with poetry, usually in high school, were with teachers who only want to talk about symbolism and iambic pentameter and make it seem as if the language of poetry is this mysterious code that only the really well educated can pierce. That is NONSENSE! Poets, like other writers, are trying to say what they mean. Now, poetry may mean something quite literally and more. But what the words say on the page are meant to be taken at face value. Of course we hope that if readers see a metaphor or an image that there are other things afoot. Maybe a different way of thinking about loneliness, or a different way of thinking about war, for example. But I never—and I think most poets feel this way—want someone to read my work and think, I know these words don’t mean what they say.

With the exception of some poets we’ve talked about—John Ashbery, for example.

Yeah, Ashbery would be one. John Yau is another one, less known than Ashbery. To my mind, they use intentionally obscure language. And so there is that—the stuff that seems to be about the poet trying to show off his cleverness. But to me that’s bullshit, basically. Language at its root evolved so people could say things to each other that matter. That’s why language exists—not for any other reason. It’s not say that we can’t have beautiful language, or complex language. But the fundamental purpose of language is that something of use can be communicated. If a poet is not doing that, I’m not sure what he or she is doing. I’m not sure what the point is.

Of course part of the responsibility is the reader’s. If you’re a lazy reader and don’t understand a poem, that’s partly your own fault. I cannot do what Hendrix or Santana does on the guitar. But even though sometimes they’re playing wildly complex things, I feel that the basic gesture is always toward opening your mind and opening your heart. And so I think that’s the thing. I don’t think any artist of any genre would dumb down stuff. But if I’m intentionally obscuring what I know, then I’m just fucking around with the reader. And that is not to be admired.

So now that we’ve trashed some major poets….

[Laughs]

…if someone who’s new to poetry is looking for poems to help them get into it, who would you recommend?

There are a lot of accessible poets. Certainly Langston Hughes was always accessible, from the time he was in his late teens until he died. Gwendolyn Brooks is another—a great, intelligent, sensitive, and quietly visionary poet.

In the more contemporary context, someone like Mark Strand can be very clean, clear and simple. And certainly if you can read Spanish, and can read Pablo Neruda in the original, you’ll hear one of the great voices of the 20th century. And if you can only read him in translation, which I have, read him in translation—still amazing.

I know you’ve mentioned before that W.S. Merwin is a major influence of yours.

Yes, for sure, although I think Merwin might be on the more complicated side in that his use of metaphor might ask a lot of a new reader. I remember reading him when I was in my 20s and thinking, I’m just not sure what he’s doing. And then bit by bit, I was like, Ohhhh. But I took it very seriously. I don’t think the difficulty is on him; he was just not writing poetry, necessarily, for an immature reader. I had to become a more mature reader to get the fuller impact.

On the other hand, there’s the great persona poet Ai, who just died recently. She captures all these different voices, and they all feel so authentic. You think, she had to have talked to all these people, but of course she hadn’t. I mean, she’s got poems in the voices of J. Edgar Hoover and James Earl Ray. There’s a long persona poem in the voice of a priest who’s a pedophile. Really just chilling. But beautiful in the sense that it is so hard to doubt the authenticity of the voice.

So let’s talk about your craft. First of all, do you write every day?

I write often. I’m probably trying to work on poems, most weeks, say four or five days in the week. Sometimes more, sometimes less. It depends of course on the poem. Some poems just grip you, and you’ve just got to be back on them every day. Other times you’re not sure what to do so you just step away.

I just finished a new book of poems not long ago, and so you take a deep breath. But after a while, it’s just the way your mind works. Something always comes back. I hear a line in my head think, maybe I should write that down. It’s not as if I’m trying, necessarily. After a while, if you’ve lived long enough, it’s as if your brain becomes this place where language just runs around, like a bunch of small crazy animals or something. And so you’re sitting around and think, Oh—yeah, and you write it down. Now sometimes it’s just nonsense. But sometimes you write something down and think, that’s really kind of beautiful or strange. And so, to answer your question, I write as often as I’m compelled to write.

What about the process of writing a particular poem? I think that for some writers, the whole thing just spills out, and then they go back and edit. Whereas for others, it’s like a miner with a pick, and chip away at it inch by inch. How do you write?

It’s probably a mixture of things. Some poems will come relatively quickly—although very rarely will I get a whole draft done in one day. That would be a rare treat. But I might get a substantial bit of what turns out to be a good poem. But even when you get a reasonably good draft, it’s probably going to take weeks, or even months if it’s a longer poem, to really find out what you’re really trying to say. Sometimes you’re just writing around, and you’re not really sure what’s driving the poem. So part of the drafting process is trying to figure out what the focus is. And then you can begin to customize the rest of the language in support of what you think is the centerpiece of the poem. But sometimes you’ll write something that is surprisingly insightful, and think, Wow—I didn’t know I knew that. Part of the pleasure is surprise. In fact, I think that in poetry, and probably all writing, if you’re not often surprised by what you’re writing, you’re probably not doing that much. I mean, if there’s no surprise for you there’s a chance that there may not be any surprise for the reader, either. And if there’s no surprise for the reader, it’s probably going to be forgotten pretty quickly.

That reminds me of how the great jazz critic Whitney Balliett described jazz as “the sound of surprise.” The great moments in jazz, it seems to me, are those that catch you off guard.

Exactly! One of the things I like about poetry is that in the draft stage it’s all about improvisation. You have no map. I love that. That is probably the thing that hooked me forever on writing.

Tell me more about your new book.

It’s called One Turn Around the Sun, and it will be published on Valentine’s Day—Feb. 14. The title poem is long—400-some lines—and it’s kind of a ranting narrative: lyrical, political, mystical, pedestrian. And it is rooted, actually, in Octavio Paz’s poem, “Sun Stone.” He wrote a line for every day it takes Venus to travel around the sun. When I started mine it was going to be 365 lines to reflect the number of days it takes the earth to travel around the sun. But it just wasn’t going to fit in 365 lines, so it’s a little longer. It’s the earth’s orbit a little out of whack, I guess. [Laughs.]

So I’m pretty excited about it. It’s a different kind of book for me. Many of the poems are me trying to recall my parents, both as I knew them and as I heard about them as younger people. It’s kind of a celebration of their lives and a farewell because, as you know, they’re not doing very well. So the tone is maybe a little more somber, with a heavier heart than is reflected in some of the other books.

We’ll see. I hope it’s not a bust. I like the poems.

It’s interesting you say you hope it’s not a bust after all the accolades you’ve gotten. But I get it. I think a lot of writers can win every prize in the world and still wonder, is this work worth anything?

I think it’s impossible to be sure about your work. I imagine it’s true of musicians, too. Hendrix actually, in an interview, was called the best guitarist in the world, and he said, well I am the best guitarist in this chair. There’s always a bit of second guessing going on. That probably makes us better writers. We work really hard not to waste our time, or waste the reader’s time.

What advice would you give to a person who would like to start writing poetry?

Well one thing I would definitely say is, by all means read poetry. But practically speaking, there are books that give you the foundations for thinking about how to write a poem. One really good book is The Poet’s Companion, by Kim Addonizio and Dorianne Lux. It gives you a number of exercises, and a number of example poems.

One of the things I did early on—and I think this is true of all writers—is that you imitate the writers you admire. That after all is how we all learned how to talk. We imitated our parents. That’s how you get a sense of what becomes, ultimately, your own style.

How much do you think talent has to do with it, versus hard work?

That’s a really good question, Tom. I do think there are people who are naturally inclined toward words. I mean, I liked to write when I was a little boy. I thought that was just normal. I have a book I had when I was 8 or 9, filled with all of these stories I wrote. Now they didn’t reflect any particular ability, I don’t think. But what they probably reflected was, Here’s a kid for whom words mattered—even back then. So maybe talent is not exactly the word, so much as that you come into the world with a particular interest in something—a delight in something. So we’re drawn to it. But ultimately much will be decided by how much you want to sweat over your work. There’s no fakin’ the funk. I say to my students all the time, how badly do you want people to pay attention to your writing? If you want to give someone the sensations you felt when reading the great writers, then you’re going to have to bust your ass.

In closing, given that you have expressed a lot of concerns in your work about society, I’m wondering how hopeful you are.

That’s a complicated question, as you and I have discussed many times. I cannot help but continue to have faith in the better aspects of the human soul. What I have come to realize is that there’s a very good chance that I will be dead and buried before the world begins to take the shape that I think it could. But if we can liberate ourselves from really bad ideologies—some of them political, some of them religious—if we can liberate ourselves from the things that oblige us to be fearful, hostile, and to under-imagine our potential, maybe we can create a world that is worthy of our children, as Pablo Casals said. And poetry for me is just part of that—a way of pointing toward a greater expanse of the mind and heart. It may be up to writers far more visionary than I to make it fully manifest. But I’m saying, Goddamit, look over there, man. This is what we might be instead of many times what appears to be this violent cesspool of stupidity. It makes my head want to pop sometimes. But I remain hopeful. I’ve just accepted that I have to be patient.