By Tom Robotham

You should be grateful for the weeds you have in your mind because eventually they will enrich your practice. ~ Shunryu Suzuki, Zen Mind, Beginner’s Mind.

Now that the summer of 2015 has come and gone, I find myself reflecting on the last three months. Did I spend my time as well as possible? It’s a hard question to answer, so I turn first to the facts. My summer in a nutshell: I saw my son graduate from college, taught a class at ODU, published some essays, played guitar, went riding at my favorite horse farm, traveled to the Outer Banks three times, got my heart broken by someone I’d long adored, enjoyed some lovely days and nights with dear friends, and watched helplessly while other friends descended into darkness.

I also got drunk a lot. Then in late July, mom died—and I drank even more.

People drink to excess for all kinds of reasons, and I had my own: the aforementioned heartbreak; a briar patch of old resentments toward my mother; a heightened awareness of my own mortality, and a profound yearning for something that I cannot quite define. I drank in hopes of escaping all of this, which is foolish, of course. Just as Jonah’s efforts to run from God proved futile, we cannot escape our own souls. At best we can find comfort in delusion for a while.

Better to turn and face the truth, as soberly as possible.

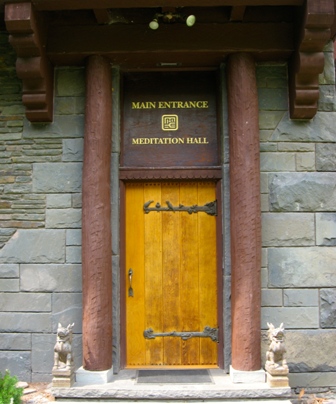

With this in mind, I decided to cap off the summer with a retreat at the Zen Mountain Monastery, in New York’s Catskill region.

I did not do so on a whim. I’ve studied Zen Buddhism off and on for more than 30 years and had known of this monastery since the mid-‘80s. The idea of a retreat there had always appealed to me, but after I moved to Norfolk in 1991 and began raising a family, carving out time for a visit to the monastery became difficult. This year, at long last, the timing worked perfectly.

“Oh, that sounds very relaxing,” several friends said when I told them of my plans.

I nodded politely, knowing full well that it wouldn’t be relaxing in the least.

At the core of Zen practice is zazen—sitting meditation. On the surface, I’ll admit, that does sound relaxing. But if you’ve ever tried to sit still on a cushion for a half hour or more at a clip, in full- or half-lotus position, you know otherwise. I hadn’t attempted it myself in a very long time, but I was well aware of its challenges, and at 5 a.m. on my first morning at the monastery I faced them anew.

The best way to begin, Zen teachers advise, is to count your breaths—but as simple as that sounds, it is easier said than done. Distractions abound, beginning with a host of physical sensations. To my surprise, my legs did not fall asleep, as they had in the past whenever I engaged in zazen. A lot of people experience lower back pain as well, but I did not. I did, however, begin to feel tension and pain in my neck, shoulders and upper back, almost immediately. Adding to the difficulty were various itches that arose. I knew that I wouldn’t reprimanded if I were to lift my hand to scratch my face, neck or shoulder, but I was also aware of the virtue of trying not to do so in an effort to settle my mind and avoid distracting the people around me. It is a useful discipline. The desire to scratch an itch commonly takes on a sense of urgency, and in everyday life we generally just succumb to the urge. But when you sit still and let the itch pass, you begin to realize that the urgency wasn’t so great after all. Physical sensations are a manifestation of mind, and it’s easy to obsess over them. But it occurred to me how relative they are. If a fire broke out in the zendo, I thought at one point, I would most certainly forget about my itch.

The extended metaphorical implications should be obvious. We live in an itchy society, but it also occurred to me that if I could let an actual itch pass, perhaps I could also resist the itch to have another drink, or lash out in anger at someone—or engage in any number of other behaviors that do no serve me well. This can be achieved not by resisting the urge with willful force but by simply observing the urge, trying to see it for what it is, and watching it pass, like a cloud in the sky.

While zazen is at the core of Zen practice, it is not its be all and end all. The idea is to carry your deepened awareness into every facet of your life. With this in mind, the people who orchestrate the retreats at Zen Mountain Monastery fill the schedule with activities. After breakfast in the dining all, they put us to work, which we were instructed to undertake in silence. My assignment the first day was in the kitchen, where I peeled carrots and stemmed fresh oregano. The carrot peeling was easy enough, but the stemming was tedious, owing to the fact that half the leaves I’d been given were purple and shriveled. Those were to be tossed in a trash pile, while the fresh green ones were placed in a bowl. After an hour or so, my neck, shoulders and back began to hurt again, just as they had on the cushion. But I understood the deeper meaning of the work assignment, which was simply to peel carrots and stem oregano—not to undertake this task absent-mindedly while thinking about my mother, or the woman who broke my heart, or all the work I had to do before the start of the fall semester. Just breathe, and peel, and stem, and breathe.

Again, easier said than done: Whether in zazen or work practice, physical discomfort is not the only distraction. Thoughts haunt us and trigger emotions in turn, which give rise to more thoughts and emotions: regrets and worries; desires and frustrations, and above all, confusion. But these, too, I found, will pass if you let them.

Another assumption that my friends had when I told them I was going on the retreat is that it would be a weekend of blissful solitude. Actually, it was quite communal, especially at mealtime and during the brief breaks that are scheduled into the day. Compassion was in abundance. The people I met were exceedingly kind, and not in that artificially earnest manner which one sometimes encounters in religious communities. Everyone there was suffering from wounds of one kind or another, so the compassion was a natural result of realizing that we stood on common ground.

During one break period, while we were waiting for a session in art practice—Japanese brush painting—I noticed a woman with whom I’d already chatted earlier. She was standing in an open doorway, looking out a gentle sun-shower falling on the meadow and the lush summer woods beyond. When I approached her and asked how she was doing, she gave me a mournful look, then tilted her head slightly as if to say, eh—so-so.

“What’s the matter?” I asked.

“Life is painful,” she said, summoning up from her own experiences a deeply personal expression of the Buddha’s First Noble Truth.

“Indeed it is,” I responded. “But there is also the beauty of summer rain.”

She smiled, and we chatted for a while longer about recent struggles in her life, then went off to see what we might learn with brushes and black ink.

To my surprise, though I’d been up since 5 a.m., I did not feel tired. Having fallen into the bad habit of drinking every night, I worried that I might have become physically addicted to alcohol and without it would not be able to sleep. I generally don’t sleep well in strange places anyway, and since we’d been assigned to bunk rooms with several other people, I feared that I might not sleep at all. That first night, though, the thought of drinking never even crossed my mind. On the contrary, I slept better than I had in a long time. The same thing happened my second night there. (There’s a lot to be said for exhaustion.) Like scratching those itches, drinking was something I’d been doing habitually and half-consciously. But that was the least of my problems, I realized—a symptom of dis-ease rather than a cause.

On Saturday, during evening zazen, we each had an opportunity for a private meeting with the monastery’s abbot, Shugen Sensei. The meeting is a highly ritualized affair, preceded by a series of prescribed bows after which the student sits on a cushion facing the teacher.

After I sat down, we looked into each other’s eyes for a moment in silence, and radiating from his was a profound expression of kindness.

“Do you have any questions,” he asked?

“Not a question, I suppose, so much as an observation about why I’m here,” I said. Lately more than ever I’ve had a very difficult time just dwelling in the present. I spend so much time turning the past over in my mind, or worrying about the future.”

“Welcome to the human condition,” he said with a slight smile.

In the dim candlelight, as he sat in stillness with his ceremonial robes draping across his black floor-cushion, he went on to remind me that with practice, one gains strength. I’d always known that to be true, of course, but for so many years it has remained an abstraction. By this point in the weekend, I was beginning to feel its truth.

On Sunday, after breakfast, we were assigned work duties once again, and this time I found myself kneeling in the soil of the monastery’s large vegetable garden, pulling weeds from a border bed. As a writer, I continually think in terms of metaphor, and now here was another, as potent as the metaphor of the itch. Over the years, it seemed to me, I’d let so many weeds sprout up in my mind for the same reason that weeds take over a garden—lack of attention from the gardener. If we allow them to get out of control, they will eventually choke the more valued plants—or at the very least, obscure their beauty.

And yet, Buddhism is filled with paradox. One of the tenets of the religion—or way of life, if you prefer—is that suffering stems from attachment to preference: A is good; B is bad. If this is true, I wondered, then why weed at all?

I can’t say that I’ve resolved that paradox, anymore than I can answer the well-known koan, what is the sound of one hand clapping? But one cannot escape the reality that to function in this world we must make distinctions. The Buddha’s Eightfold Path, after all, prescribes the way to Enlightenment as a matter of Right Thinking, Right Speech, Right Action, and so on. The weeding must be done, but with the same attention and awareness with which one, ideally, undertakes every other task. And that means, in this case, an awareness that one is destroying life.

They’re just weeds, you might say, and I realize that my observation may sound a tad dramatic. But it’s true. We cannot survive—we cannot eat—without destroying life of some kind, even if we are vegetarians, which most Buddhists are. The question is, are we doing so with respect, which is, at its root, synonymous with attention. Re-spect: To take another look.

As I continue my practice of zazen at home—and my efforts to carry its spirit into my varied activities of each day—I continue to contemplate the weeds that have grown in my mind: Some must be rooted out—in particular, old resentments, and worries about things over which I have no control. Others, perhaps, can be allowed to remain. Some weeds are lovely, after all. But all must be observed with intent, and considered for what they are, not attacked carelessly.

What is this, and how deep are its roots? How is it affecting everything else around it?

On the cushion, these questions arise and fall, and the best we can hope for are some tentative answers, not through hard analysis but by simple observation of the nature of things. In time, such practice can lead to right action—a gentle and graceful avoidance of things that might poison us, a cultivation of compassion, and ultimately, an awareness of the fullness of life in both its endless manifestations and essential oneness.

These are just words, of course—and ultimately, words fall short. Zen teachers frequently say that they are engaged in an effort to teach what cannot be taught. Likewise, as the Tao says, the ultimate Truth of existence cannot be named—cannot be put into words. (Zen, by the way, while a branch of Buddhism, also owes a debt to Taoism.)

And so, in the end—with faith in this ancient practice—one returns to the cushion, again and again, simply to sit and be still. In our impatience, we inevitably are assaulted by thoughts: nothing is happening! It’s not working! I can’t do this! And so on.

I won’t presume to say that these thoughts will always pass, for everyone. For you, they may not. Zen teachers are quick to say that the practice is not for everyone—an attitude that distinguishes it from, say, the more evangelical branches of Christianity, which seek to impose their tenets on the world.

At times, I’ll admit, the retreat felt very religious, indeed. Part of the schedule is devoted to Buddhist liturgy, and it is every bit as ritualistic as high Catholic mass, with bows and incense, bells and chants. For my part, though, I long ago realized that if I simply dwell in ritual without intellectually analyzing every word—whether I’m reciting the Nicene Creed or the Heart Sutra—it will have a mysterious effect beyond intellectual understanding. And the effect is this: a cultivation of the sense of the sacredness of life.

The chant during our liturgies that stood out most vividly for me was this: “Let me respectfully remind you: Life and death are of supreme importance. Time swiftly passes by and opportunity is lost. Each of us should strive to awaken. Awaken [and] take heed—Do not squander your life.”

That last line struck a nerve. For a long time now I’ve had the sense that I squander far too much time that could be devoted to writing, mastering a musical instrument, earning money, doing chores or what have you. At the same time, it occurs to me that many people today suffer from another kind of dis-ease—a constant busyness, fueled by the anxiety that one must always be productive.

I do not believe that the last line of the chant is affirming or validating this way of living. Just sitting, after all, hardly appears to be productive by Western standards. No, there are many ways of squandering a life. One can do it just as easily through mindless addiction to work or a jammed up social calendar as one can through abuse of drugs or alcohol. In both cases, what’s lost is awareness—the state of being fully awake.

Some people are more naturally awake than others, I think, and for them the practice of Zen may be wholly unnecessary. All I can say as I closed out a summer of both beauty and trauma is that it is precisely what I need: the practice of simply sitting still, while neither clinging to desires nor fighting the pain. Rather, the object is to just sit and observe them all. In time both pleasure and pain will pass, and something new will arise in their places. Will I be ready for that new thing? I do not know. But tomorrow I shall return to my cushion once again, in preparation.