By Jim Morrison

While the COVID pandemic forced many artists into secluded hibernation, it provided Roberta Lea with the opportunity to venture down the path of a new career.

Lea, who dabbled in songwriting and played open mics since she was a teen two decades ago, was teaching Spanish at Booker T. Washington High School when she made her pandemic pivot from lecturing students to performing on stages across the country.

“During 2021, we went to virtual,” she recalls. “We weren’t in the classroom. I didn’t see my kids. They were teenagers, you know, high school. So they just kept their cameras off. There was just no connection. The world was changing. And the pandemic really made it clear that life was very short. And so if there was a time to give it a shot, maybe now’s the time to do it before I didn’t have that chance anymore.”

After the school year finished, she quit and threw herself into songwriting and performing. Again, COVID figured in the path she took. But so did her passion and commitment to the way ahead.

During the pandemic, she grew bored of hanging out on Facebook so she turned to Twitter (now X). There, she connected with Holly G. a writer and flight attendant who grew up loving country music but felt it had abandoned her. She’d created a website writing about artists of color. Within weeks, she was awash with messages from supportive artists and fans.

Lea and Holly G. also followed Rissi Palmer, a songwriter and host of Color Me Country Radio. The three of them – Black women — didn’t see anyone else who looked like them in an industry that caters to the white Bro culture. A study by a Canadian musicologist confirmed their view. Over two decades, only 1.5 percent of the artists on country radio were Black or Indigenous.

At Holly G’s urging, they met at Americanafest 2021. Lea considers it the first meeting of Black Opry, an organization promoting Black country artists founded earlier that year by Holly G.

“I guess I could say I was with the Black Opry at the inception, really, because Holly was creating the blog where she was developing the profiles of Black artists that did country music and, and she just grabbed my hand and pulled me along,” Lea says. “She connected with everyone online and reached out and said, Hey, we’re, we’re going to be down at Americanafest, come through. And it just blew up from there.”

Out of that, The Black Opry Revue was born, a rotating list of two to four Black country artists that has included Lea, Palmer, Joy Clark, Tylar Bryant, Lizzi No, and Miko Marks, who opened for Little Feat at the Sandler Center last year and will be part of the Trailblazing Women of Country show with the Virginia Arts Festival this spring.

After playing across the country, The Black Opry Revue comes to the Sandler Center on February 16. Lea will be joined by Julie Williams, Jett Holden, Whitney Monge, and Bryant and backed by a band. “I’m just very excited that Black Opry is finally going to be here in Virginia,” Lea says.” I’ve been touring the whole world with them. And I’m like, we’re finally home.”

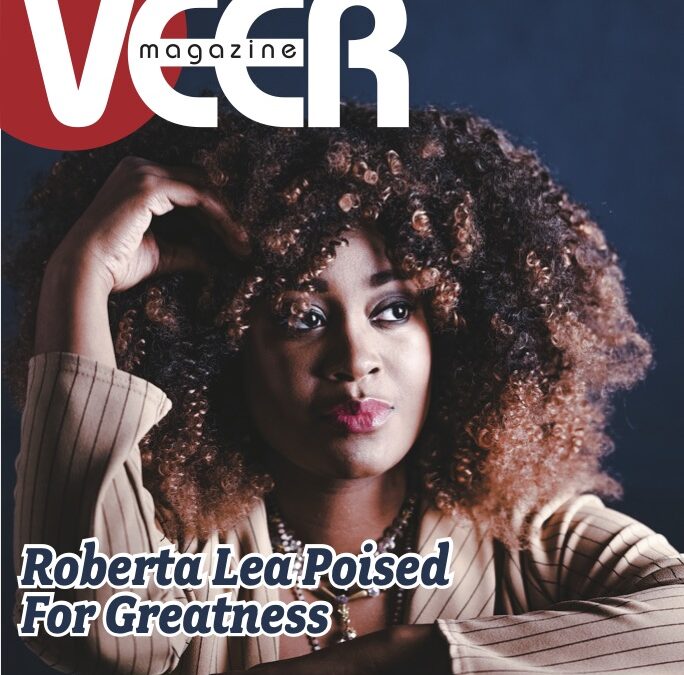

Lea has been nominated for several Veer Music Awards, including Album of the Year, Song of the Year, and Music Video of the Year. She will also be playing a show on Feb. 23 at Zeiders American Dream Theater in Virginia Beach.

After releasing an EP, “Just a Taste,” in late 2021, she broke through with last year’s “Too Much of a Woman.”

She funded the album through Kickstarter with help from Brandi Carlile and Allison Russell, who championed her campaign. Lea met Russell, who has played in Norfolk three times in recent years before her solo debut exploded, at that same Americanafest.

“She gave me her contact (information). She was just very wide open, and very kind. And we just stayed in touch,” Lea adds. Russell became increasingly busy, but the connection endured. When Lea started her Kickstarter, she reached out to Russell and others who had been supportive, including Maggie Rogers. Russell contacted Carlile, who joined in support.

As Lea entered Soul Haven Studios in Virginia Beach to begin recording last winter, she learned she would be included in the 2023 class of CMT’s Next Women of Country. The Nashville Scene added to expectations by naming her an artist to watch in 2023.

She’d worked with John Terrell at Soul Haven before and asked him who might be good to collaborate and co-produce the record. He connected her with Larry Berwald, a member of Wet Willie who plays with numerous area artists. He recruited local musicians for the recording. She also used her band, Best Kept Secret. “For me, it was a great community effort,” she adds. “I wanted to make sure I did it here in Hampton Roads.”

Lea has been writing songs since she was a teen. While teaching, she regularly played open mics like “No Covers” hosted by Joselyn Best and pop-ups arranged by Jim Bulleit.

While she has gotten attention as a Black country artist, a listen — and her background — reveals a much wider foundation.

She grew up in Norfolk, the youngest of three daughters. Her mother favored Gospel, jazz and old-school R&B. They listened to 103 JAMZ and Quiet Storm. Her older sister was a Z104 fan. They listened to Sheryl Crow, Alanis Morrissette, Jewel and Tupac. When Lea started going to church as a teen, she got into Kirk Franklin and Casting Crowns. Then it was Shania Twain, Faith Hill, Anita Baker, Tina Turner, and Roberta Flack. “It was everywhere,” she says.

“Too Much of a Woman” reflects her range. The opener, “Somewhere in the Tide,” is soulful folk. “Girl Trip” edges into what might be called Twainian hip hop. The title cut is a powerful anthem. “Stronger This Time” merges the horns of the Norfolk Sound with an old country string feel. “Dinner, Sunset, Nina SImone” dips into jazzy soul. There’s also an intriguing and beguiling reimagining of “Papa Was a Rolling Stone.” It’s an enticing journey.

“I really don’t think too much as to what kind of genre it’s going to be,” she says. “As a storyteller, I have a lot of songs that lean into country music that may not be associated with what most people consider country music today. I am a country music artist as in a storyteller. Folk, the blues, Gospel, all of those strains are weaved into a fabric. That is what made this country music to me. And that’s why I feel like it feels like home. ”

Is it hard to convince a room of listeners that a Black performer is a country artist? Lea takes the long view, going back to the roots of music.

“In some experiences, it does feel hard to convince the room but it definitely makes sense when we realize that genre was created based on perception not necessarily sound,” she says. “Country music and R&B were essentially the same exact thing. But if you were a white artist playing this guitar, they would call it hillbilly music. And if you are a Black artist playing the exact same guitar and using that same song style, they will call your genre race records. And then they branched off and became country music and R&B.

Look at “I Will Always Love You” by Whitney Houston and Dolly Parton right? It’s the same exact song. And with a little bit of reimagining, it fits perfectly in country music and R&B.”