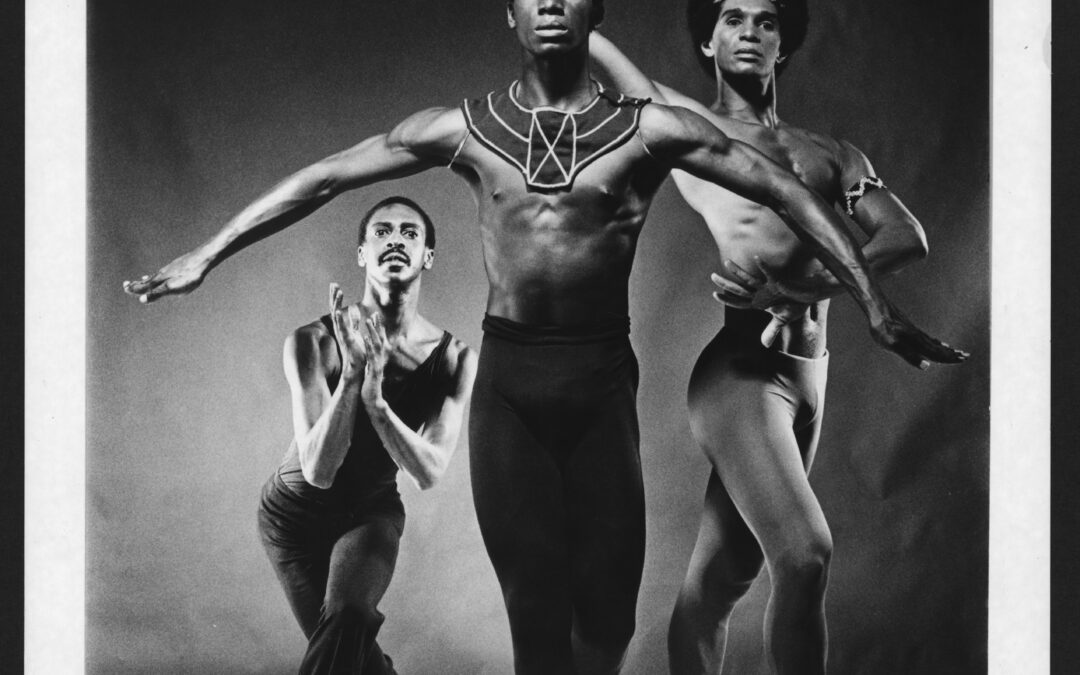

Elbert Watson (center) in a photo by Jack Mitchell. “Three Black Kings”: Dudley Williams as Martin Luther King, Jr., Elbert Watson as Balthazar and Clive Thompson as King Solomon dance in Alvin Ailey’s paean to the three historic figures. The work was set to the last music composed by Duke Ellington.

By Kate Mattingly

When the Virginia Arts Festival (VAF) began in 1997, two things were different: it was called the Virginia Waterfront International Arts Festival and there were some haters.

Anytime an international festival is established in a community, there are locals who view the importing of performances by global artists as either taking away from local venues or competing with local artists. In actuality, the VAF has a four-prong mission: it’s committed not only to hosting “world-class performing arts,” but also to educating students, commissioning artists, and making “a tangible difference in Hampton Roads through regional partnerships and cultural tourism.”

The VAF boosts income in the Hampton Roads region as well as the state. The 1998 festival brought more than $5.6 million in spending to the region and $5.2 million to the state. The 2023 festival is estimated to bring in more than $25 million. This income benefits local venues which host festival events that enrich and amaze audience members. Artists presented by the festival include Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater and Philadelphia Ballet, as well as musicians like Yo-Yo Ma and singers like Renée Fleming.

Robert W. Cross, VAF’s founder as well as its Executive Director and Perry Artistic Director, says that honoring local artists is also a vital part of the festival. “There are many incredible artists who are either natives of Hampton Roads, or who have made their careers here. These people have not only made a huge difference in this region, but they’re also nationally, and, in some cases, internationally recognized.” Cross established the Ovation Award in 2019 to acknowledge these extraordinary individuals: its first recipient was dancer and teacher Lorraine Graves, and its second recipient, in 2022, was music director and conductor Rob Fisher.

Cross emphasizes how these artists have “had a big impact,” meaning they have transformed the landscape of the art forms they pursued. “And I think we need to be honoring our own,” he adds. When Cross designs a ceremony for the annual Ovation Award recipient, he not only invites their colleagues and students, but also some of their own local teachers.

This year, on April 29, the Ovation Award recipient was Elbert Watson, who grew up in Norfolk, attended Booker T. Washington High School, and went on to become a principal dancer with Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater (AAADT), as well as a choreographer and beloved teacher. His ceremony included a speech by Matthew Rushing, who danced with AAADT and now serves as the company’s associate artistic director. Rushing was in Norfolk while AAADT performed at Chrysler Hall, and spoke about the indelible impression Watson made when Rushing watched recordings of his performances. This is exceptional praise coming from such an esteemed artist.

In 1984, Watson joined the faculty of Norfolk Academy and developed far-reaching dance and conditioning programs. Ballet dancer Lauren Sinclair met Elbert in 2006, during a moment in her career when she was losing her love of dancing. She remembers her first class with him at Norfolk Academy, an evening class for dancers who range in age from upper teens to 70s and who hear about Watson through friends (he does not advertise). “I immediately felt his warmth and support,” Lauren says. “He’s just so genuine.”

Lauren was dancing with a company at the time and went to Watson for classes and coaching. “He really helped me find my way, ‘the Lauren way,’ of dancing. He does this for all of his students. He’s good at finding how a step works best on your body and for your mindset. I was a dancer who didn’t breathe often enough, so he would choreograph when I should inhale and exhale. To me, working with Elbert felt safe: he holds space for people. If you’re having a bad day, he’s going to let you cry and be frustrated. If you’re having a great day, he’s going to celebrate with you.” While this kind of encouragement may sound obvious, in some ballet classes, teachers do not allow students to show feelings, especially frustration. Lauren adds, “He took me under his wing, guided me, and encouraged me.”

Today, as a teacher at Old Dominion University, Lauren shares the knowledge and support she received from Watson with future generations of dancers. Her classes are distinguished by her warmth and care, as well as her deep knowledge of ballet: just as Watson did for her, Lauren finds ways for each dancer to excel. “He’s kind of like a secret,” she adds, explaining the no-advertising approach. “It’s a well-known secret,” she says laughing.

“I don’t really remember details of that first class. It’s blurry after that many years, but I still have an email I sent my then-boyfriend, now-husband that said, ‘I haven’t had a class like that in years! It was inspiring, motivating, and he just really made me want to dance… at least now I know that I want to keep dancing!’”

Asked what distinguishes Watson as a teacher, Lauren says, “He always teaches his students that everyone wears many hats. A lot of times we think we are on the dance track and we only can wear the dance hat. For me, he said, ‘You can be a mom, you can be a wife. You can read, you can go to the beach, you could go to church. You can take a break from dance and dance will always be there for you when you return.’”

This ability to pursue multiple paths reflects Watson’s own career: he not only danced with Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater, but also performed in the choreopoem “Boogie Woogie Landscapes” by Ntozake Shange, who wrote “For Colored Girls Who Have Considered Suicide/When the Rainbow is Enuf.” This play was choreographed by Dianne McIntyre and performed at Symphony Space in 1979. That same year, Watson appeared at Carnegie Hall as guest dancer with the Pearl Primus Afro/American Dance Company. Primus, McIntyre, and Shange are giants in the history of dance and performance. Since their dances live on in the bodies of artists who performed their choreography, Watson is a walking encyclopedia of dance history.

As a member of AAADT, he performed classic repertory by Ailey, such as “Night Creature” and “Revelations.” He was frequently singled out for exceptional performances by critics in the New York Times. In 1976, Clive Barnes wrote about Ailey’s “Three Black Kings:” “The ceremonial of the magi, played well by Elbert Watson, had its stately grace.” He also performed choreography by Janet Collins, the first Black dancer to perform at the Metropolitan Opera, when AAADT commissioned her to create choreograph “Cantina of the Elements” in 1974. In a New York Times review Watson is complimented as being part of “an attractive earth trio,” with Warren Spears and Donna Wood.

As a choreographer, Watson won accolades from New York Times critic Anna Kisselgoff, who named his piece “Reins” one of the “best” pieces on a 1977 program and one that “elicited the most enthusiastic audience response.” The review continues: “In ‘Reins,’ Mr. Watson used a line from Yevtushenko (‘Hurry is the curse of our century’), to suggest a range of human relations within a mock race. The movement was often vivid and Mr. Watson has a flair for working with groups.”

Lauren continues listing the attributes that make Watson special: “His lessons go beyond the dance class. They are life lessons. For example, he taught me how to say, ‘No.’ I would get offered a teaching or performing job and he would say, ‘Do you really want that?’ And I’d say, ‘No.’ And he told me, ‘Well, you can say no, and you don’t have to tell them why you’re saying no.’” As trite as this may sound, dancers in ballet, especially female dancers, are frequently taught their skills are replaceable, and everyone is expendable. Watson defies this approach by reminding every student of their value.

Norfolk, a relatively tiny city, is home to many great dance programs, but the dance landscape is mired by one-upmanship: for decades, one school claimed it offered “Hampton Roads’ premier pre-professional dance training program,” and seemed to equate teaching ballet and Hawkins-based modern dance with being the “best.” When dance teachers are reluctant to honor a variety of dance styles, or to highlight the assets that exist in every program and to be open to feedback, students suffer. By developing a multifaceted and interdisciplinary program at Norfolk Academy, Watson has been able to amplify the richness of a wide spectrum of dance genres. And it’s a spectrum that he embodies.

It’s also an approach that aligns with Virginia Arts Festival’s music programming: many genres are presented, and this encourages cross-pollination of audiences and artists. For dance audiences, the festival tends to present mostly ballet companies and modern companies led by white men like Mark Morris and Richard Allston who make ballet-based dances. As a result, audiences miss out on dance-theater, choreopoems, and contemporary approaches. We only see a tiny sliver of the dancing that exists in our world, and that Watson himself has created and performed. And schools tend to think they are “premier” if they emphasize ballet.

While the festival has made “a tangible difference in Hampton Roads” economically, its impact on dancers and dance audiences could be seen as less enriching. Watson exemplifies the value of honoring multiple techniques and exploring different approaches to dance-making. Companies that have never been presented by VAF, and who could tap into the hip hop, contemporary dance, and universities of Hampton Roads, include Yin Yue/YYDC, LaTasha Barnes/The Jazz Continuum, Compagnie Hervé Koubi, Rosie Herrera Dance Theatre, Camille A. Brown & Dancers, SOLE Defined Percussive Dance, and Ill-Abilities. Presenting a range of dance artists makes it possible for younger dancers to see themselves in their movement and messages.

As Lauren explains: “Elbert doesn’t try to change who he is to please others, which is why I think he’s had such a successful career in teaching. He’s authentically himself and that’s what he wants for everyone he meets. A lot of times, I have felt pressure to mold into what’s in or hip. He’s always followed his own path. And he continually pushes himself in ways that make him grow. He’s simply a great person. I’m not only a better dancer because of him, I’m a better person because of Elbert.”