By Jerome Langston

While a fellow at the Newark Museum of Art back in 2015, curator Kimberli Gant, PhD, discovered a significant connection between African-American painter Jacob Lawrence, regarded by some as the most celebrated black artist of the 20th century, and a then burgeoning scene of artists and thinkers in Nigeria, back in the 1960s. This discovery while viewing Lawrence’s catalogue raisonné—which is remarkably the first one dedicated to the work of a black American artist, led to Gant further inquiring about the time that Lawrence spent in Nigeria in the early 1960s, his little-known Nigeria series, and how that all connected to the Mbari Artists & Writers Club, an important arts organization of Nigerian based writers, artists, intellectuals and musicians.

“Initially was thinking I could do a small project on this series, while I was there, and it became clear that it needed to be bigger than that,” says Gant. “There were some broader discussions that needed to be thought about and considered.” She brought the initial idea of Black Orpheus: Jacob Lawrence and the Mbari Club, with her appointment as curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at Norfolk’s Chrysler Museum of Art, at the beginning of 2017. Gant is now the Brooklyn Museum’s curator of Modern and Contemporary Art, a position that she’s held since just this past January. She was nevertheless determined to launch this large exhibition of Lawrence’s lesser-known Nigerian inspired artwork, alongside the work of a diverse spectrum of artists whose works were either featured at the Mbari Club’s exhibition space in Ibadan, Nigeria, or were part of Black Orpheus, an arts & literary journal founded by the Mbari Club, which featured fiction, non-fiction and art reviews pertaining to the African diaspora. Black Orpheus was published from 1957-1967.

Alongside her co-curator Ndubuisi Ezeluomba, PhD, VMFA’s curator of African art, Gant has gathered over 125 pieces that are now on display as part of the Black Orpheus: Jacob Lawrence and the Mbari Club show, which will remain on view at the Chrysler Museum till early January, and then will travel to the New Orleans Museum of Art. These items include paintings, sculpture, letters, and archival images, amongst other art. It took years to gather this impressive collection for exhibition. “Some works are from institutions, but also a lot are from private collections,” Gant tells me. Her process included talking to galleries, auction houses and collectors.

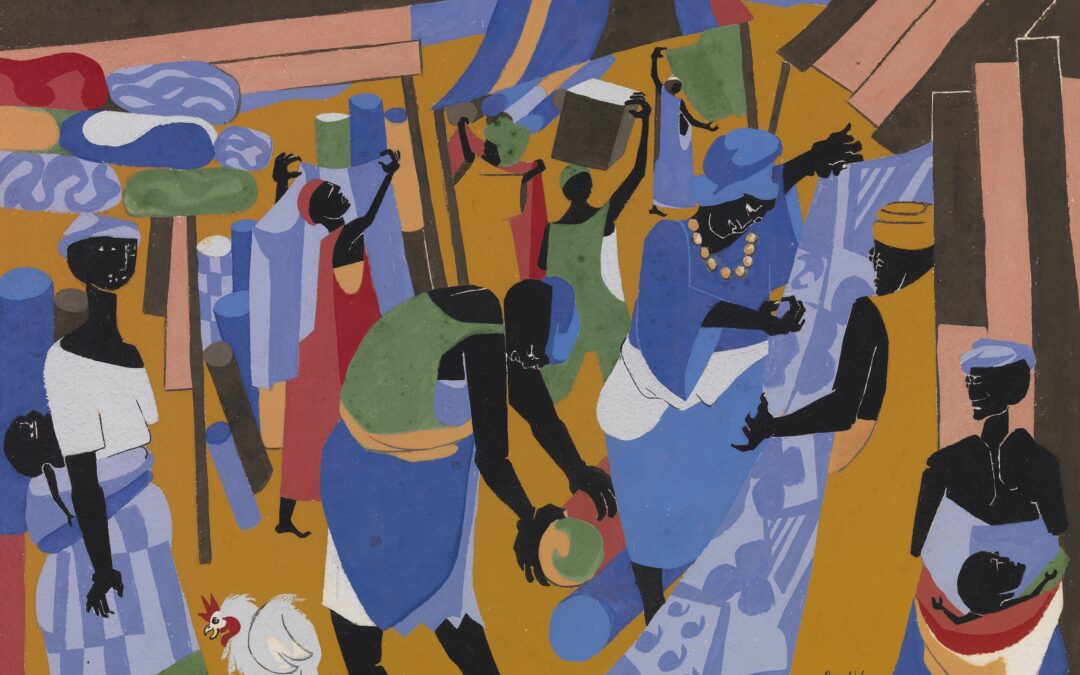

“Lawrence is the marquee artist, but there are artists from Nigeria, from Ghana, Sudan, Ethiopia…from Brazil, from India…” she says. Indeed, works by Ibrahim El-Salahi, Francis Newton Souza, Genaro de Carvalho, Avinash Chandra, and many others are featured in this show. Some of the extraordinary works include Lawrence’s Market Scene, 1966, Nigerian artist Jacob Afolabi’s Rich Merchants from Northern Nigeria, Avinash Chandra’s Untitled, 1965, and Face, 1956, by Francis Newton Souza, from India. Gant has also displayed the Black Orpheus journals themselves, with their creative covers and African art aesthetics, but “the juice and meat of the journals is in its pages,” the curator says, “So we have digital copies of the journal.” Thereby allowing museum visitors to read the content included in the magazine.

It is truly a lovely, expansive exhibition of largely African diaspora art, that requires more than a cursory view to appreciate in its entirety. During the members’ exhibition preview this past Thursday, the co-curators gave a talk where they explored the genesis of the Mbari Club, the dynamics of a post-colonial Nigeria, following its independence from Britain in 1960…and of course what drew Jacob Lawrence to the African country.

“This was a moment where there was so much happening that was both engaged with the international modernist art scene, but very much also rooted in local practices and traditions and ideas,” says Gant, about Nigeria’s art scene during this period in the 1960s. Lawrence was long interested in the impact and history of African art. He was associated with AMSAC, the American Society of African Culture. The relationships that developed from there, would lead to a number of his series work being exhibited in Nigeria. That included part of his famous Migration series. His first visit was reportedly in 1962, but was only for a bit over a week. He returned though, with his wife, in 1964, and stayed for eight months. That allowed him to really soak up the arts scene, and connect with some of his contemporaries there, as well as the emerging, younger artists of that day.

“He knew that the basis for so much Western practice that we see as the kind of epitome of art, was based on African form, African ideas—whether they wanted to admit it or not,” says Gant. “He was very much aware that culture really started in Africa. And he wanted to experience that.”

Towards the end of our chat, I ask Kimberli what she wants members of the public, who view the exhibition, to take away from it, if anything. “I hope that people see that this show is really trying to show the importance of artistic exchange and conversation.”

M

“Black Orpheus: Jacob Lawrence and the Mbari Club”

Through January 8

Chrysler Museum of Art

Chrysler.org