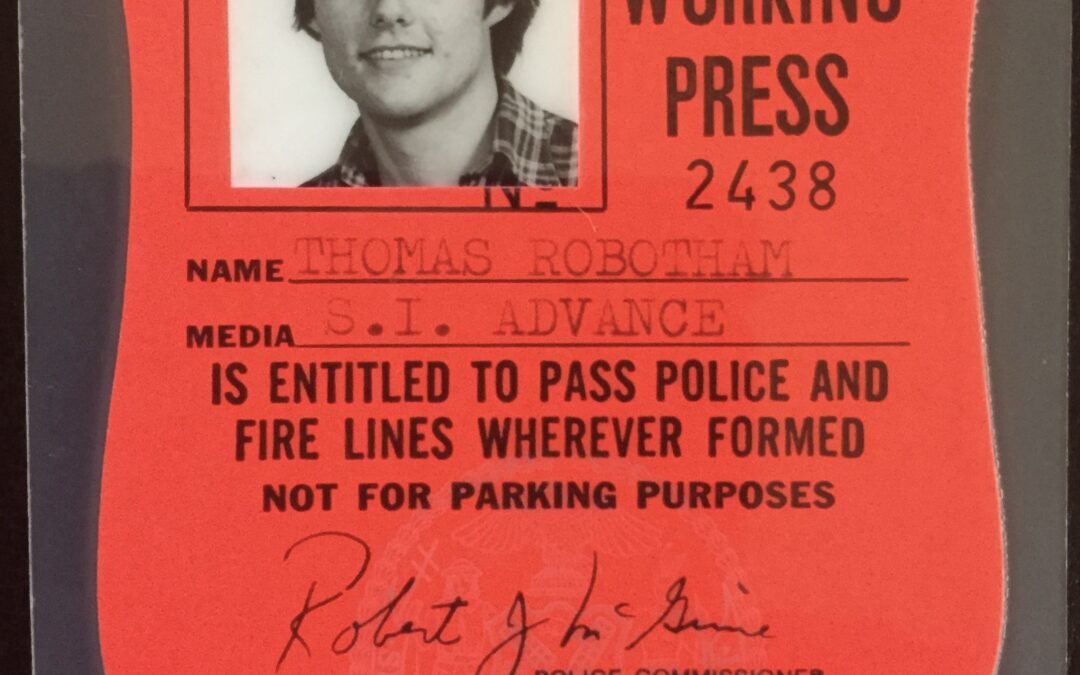

NO EASY BEAT: Tom Robotham’s “backstage/all access pass” to the frontlines of NYC’s crime and fire scenes in the late 1970s.

By Tom Robotham

Recently on Facebook, I saw a meme asserting that there’s no such thing as a good cop: they’re either dirty, clean but afraid to speak up, or courageous enough to do so—and therefore get pushed out. It got me thinking about all the cops I encountered when I landed my first newspaper job and was assigned to the police-and-fire beat.

At the outset, I already had a bias against cops, based on experience.

One moment in particular stands out. I was 16, hanging out with a group of friends in front of the public school in our neighborhood. It was around 7 p.m. We weren’t making a lot of noise, although we did have a small radio playing—likely the song “Brandy,” by Looking Glass, as it was pervasive that year.

Anyway, we were being pretty mellow when a guy stormed out of his house with a gun in hand. He identified himself as an off-duty cop, then proceeded to lecture us on our juvenile delinquency, stopping to smack each of us in the head as he moved down the row in which we were sitting on a stone ledge. After that, he told us to stand up.

“You’re the tallest,” he said to one of the guys. “C’mon,” he added, grabbing the kid by the hair and pulling him across the street.

The rest of us sat there, unsure of what to do, but after about 10 minutes, our friend came back out. He told us the cop had dragged him into his kitchen, demanded his home phone number, then called his mother, to whom he barked, “What would you do if I told you your son was dead?”

Our friend could hear his mother’s scream through the receiver. Then the cop said, “Well, he’s not—I have him here. But you need to get control of your boy.”

My friends and I had many other encounters with police, whenever he hung out in the schoolyard, and they were always a pain in the ass. That said, it mostly seemed that they were just doing their jobs. This guy, on the other hand, was a true pig, and for a long time he colored my whole view of the NYPD.

My initial experience on the beat, six years later, wasn’t awful. But making the nightly rounds wasn’t pleasant either. The desk sergeants were generally contemptuous of reporters, and cops at scenes could be even worse. One of my first assignments was to go to a murder scene—a jewelry store where the owner had been held up at gunpoint and had reached for the shotgun under the counter but wasn’t quite fast enough. When I got to the store, I tried to make my way past the police lines. Since I had an NYPD-issued press badge explicitly allowing me to do so, I was taken aback when an officer forcefully pushed me away and said, “That thing don’t mean shit.”

And so I learned on the job: This ain’t gonna be easy.

Firefighters always seemed a lot friendlier. When I’d visit firehouses, I’d generally find a group of guys hanging out and eating some feast that one of them had cooked up. At fire scenes, on the other hand, I didn’t attempt to speak to any of them while they went about their work, other than the fire marshal to see if he suspected arson.

One fire is especially memorable: a five-alarmer in a low-income Puerto Rican neighborhood. As I stood watching the apartment building burn on that icy winter night, a young woman with a swaddled baby in her arms came up to me and said something in Spanish.

“No hablo Español,” I responded, but she didn’t hear the “no” and proceeded to talk in a pleading tone. My high school Spanish was beyond rusty, but it was clear that she was begging me for information. I was sorry I had little to offer.

When all was said and done, 30 families were homeless. Freezing and shaken, I went across the street to a bar, downed two shots of tequila, then drove back to the office to write my story.

While that stands out, covering police business took up the bulk of the job. I went to a lot of car-accident scenes, and that was pretty brutal. But it did change my view of cops, somewhat. I remember one night when a teenager totaled his car. I followed the ambulance to the hospital, and as I sat in a waiting room, I watched a cop, on a payphone, tell a woman (he’d addressed her as Mrs.) what had happened. I couldn’t quite make out whether he revealed the harshest of truths—that her son was dead—or just that he was in the hospital. But I felt sick, imagining what was going through the mother’s mind. At the same time, I also felt bad for the officer. I was glad I didn’t have his job.

Covering murders was just as rough. One time, I arrived at a murder scene—a modest house on a tree-lined street—to see two sheet-covered bodies lying in the hallway. A cop told me it appeared that the dead man and his wife, who were quite elderly, had had an argument and that, in anger, she had ripped up his beloved tomato plants. He, in turn, had hit her in the head with a hammer, then hung himself.

What stands out about that memory, in addition to the horror of the scene and the gut-wrenching story, is that the officer and his partner were joking about it. Initially, I was appalled by their apparent heartlessness. Sometime later, though, I mentioned this to another cop whom I’d gotten to know a bit.

“It’s just how we deal with the shit we see,” he said. “If we didn’t crack jokes, we’d go nuts.”

That always stuck with me.

My most vivid memory of those days, though, is of another murder. I was making my rounds when the desk sergeant at the 122nd precinct said, “You might wanna take a look at this.” I was initially pleased that for once a cop seemed friendly, until I saw the report: A 35-year-old man had been found bludgeoned to death in his apartment.

“Heard the guy was a popular school teacher,” the sergeant said. “No clue why somebody’d kill him.”

When I got back to the office, I was unsure of what to do next.

“Call everybody in the phonebook with his last name until you get a relative,” my editor said.

Since his last name wasn’t terribly common, it didn’t take long. I asked the woman who answered my second call if she knew the man in question, and she said, yes, she was his mother. When I explained why I was calling, she said, “How dare you bother us at a time like this.” I apologized and explained that I was just trying to do my job—at which point she apologized and opened up about her son. The next day, after the story was published, my editor complimented me. But I didn’t feel proud. I kept wondering what business I’d had calling her. Maybe it was cathartic for her, maybe not. To me it felt like exploitation.

I lost my taste for the crime-and-fire beat after that—and thankfully, I got a new beat soon thereafter. Still, I’m glad I was exposed to these dark and gritty realities.

Sometimes, in fact, I wish I could do it all over again and go deeper—to immerse myself in cop-world and try to understand their challenges and what makes them tick. For in spite of the arrogance I’ve encountered from cops over the years—here in Norfolk, on occasion, as well as in the NYPD—I have tremendous respect for the job. I’d like to know more about the people who do it—the people who risk their lives for modest pay while often taking abuse from all directions.

That’s not something we talk much about. Instead, the news media tend to focus on abuse by cops. Those stories certainly need to be covered, and the cops in question need to be held accountable. I just think we need to understand and appreciate the tremendous stress of the job as well.

To some extent, it’s shared by other first responders. My closest childhood friend eventually became a firefighter. His first assignment was in the South Bronx. When I ran into him one day and asked about his job, he said it was tough. They’d show up to a fire, he told me, and some of the residents would throw rocks and beer bottles at them.

His story piqued my curiosity: Why would people do such a thing? I wasn’t about to go the South Bronx to find out. The neighborhood back then was essentially a war zone. But a few months later, I ventured into some high-rise “projects” on Staten Island to interview an up-and-coming jazz drummer, who’d grown up there and bucked the odds. The housing complex had a stench of both urine and hopelessness, and was a glaring example of a system gone wrong. For a moment I understood the rage that might lead some people to want to burn it all down.

But I sympathized with my friend as well. His job was dangerous enough in the best of circumstances. He didn’t deserve to be pelted with rocks.

Police officers face hostility as well, especially in impoverished inner-city neighborhoods where they’re often seen as oppressors. This is certainly understandable, but it puts every cop—including those who have no history of brutality—in a bad spot. Think about it: Whenever they respond to a call, they’re expected to run toward danger. Then what? Imagine you’re a cop, and you confront someone at an alleged crime scene. It’s so dark you can barely make out the features on the person’s face. You tell him to freeze, but he reaches into his pocket. Do you pull your gun and fire? You have to make a split-second decision: Are you going to hold your fire and risk dying yourself? Duck behind a wall and let the suspect get away, knowing that you’ll likely be reprimanded for dereliction of duty? Let’s say you decide to shoot—then you learn that the person was just pulling out his cell phone.

When I sketched out this scenario in conversation with a friend recently, he responded that cops usually get cleared for such shootings.

Legally, yeah. But they still have to live with the knowledge that they killed an unarmed person. It seems to me that we often forget about these sorts of things because—swayed by all the horrific reports of brutality—many of us tend to dehumanize cops.

Some might respond in turn that cop culture is to blame: Specifically, the “Blue Wall”—the code of silence that each rookie learns. Never report a fellow officer for bad behavior.

There’s something to be said for that criticism. And yet, I understand the mentality behind the code—the idea that when you’re putting your life on the line as a routine part of your job, you need to know that other cops have your back. Let me be clear: I’m not defending the code; I’m just trying to see the job from a cop’s point of view.

Hence, my earlier statement that I sometimes wish I could do that first beat all over again and spend more time trying to understand the tensions between cops and civilians from all perspectives. After all, the world being what it is, we need police. And since, we need them, it seems to me, we need to give them some consideration.

I’m not sure I’d have this point of view if I hadn’t covered that beat. In the process, I met all kinds of cops, albeit all men, since women cops were exceedingly rare back then. Among them, to be sure, were walking stereotypes: overt racists and bullies who wore their bloated machismo on their sleeves. But I also met a lot of others: fresh-faced rookies who looked awkward in their uniforms; wise and witty detectives; gray-haired veterans who were working desk jobs, biding their time till retirement, and a lot of journeymen officers—decent guys who were doing the best they could while hoping to make it home, at shift’s end, to their wives and kids.

Back then, the racist bullies tended to get a free pass. I’m glad that’s starting to change. It’s long overdue. But the simplistic attitudes on the far left—which led to the foolish “defund the police” movement—are counterproductive. In fact, they’re just the flip side of the same coin: The right tends to think cops can do no wrong (well, unless they’re guarding the Capitol) and the left seems to want to hold them to superhuman standards. Both the job and the people who do it are a lot more complicated than that.