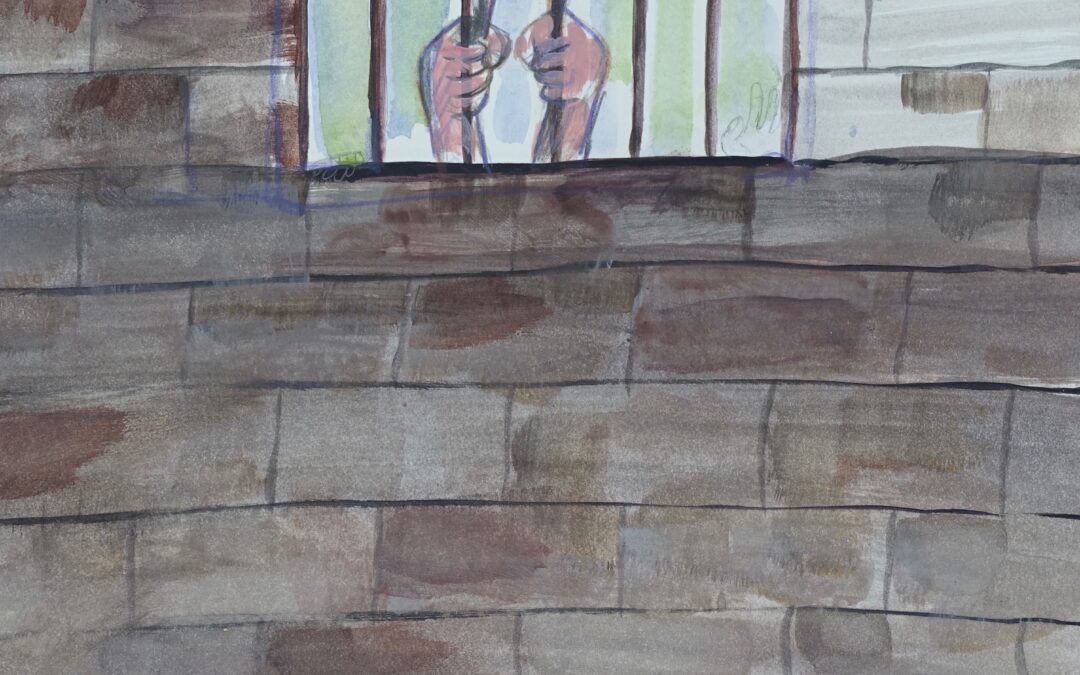

Muhammad Ansi, Untitled (Hands Holding Flowers through Bars), 2016, acrylic on paper, 11 x 8.5 inches

By Betsy DiJulio

Six artists. Over 100 artworks. Fifteen years, give or take. The artists in this rare exhibition include both current detainees at Guantánamo Bay (Moath Al Alwi and Ahmed Rabbani) and former (Muhammad Ansi, Abdualmalik Alrahabi Abud, Sabri Al Qurashi, Mansoor Adayfi), none of whom were or have been charged with a crime. In the following Q & A, Cullen Strawn, ODU’s Executive Director for the Arts, looks beyond the numbers to share why, in terms of both context and content, this collection of work from a distant island is richly relevant to citizens of Hampton Roads and beyond.

Betsy DiJulio: Why was this exhibition the right exhibition at the right time? That is, how does it dovetail with your Gallery’s mission and why was this the right moment in which to share this work vs. any other work?

Cullen Strawn: I have worked toward the exhibition for five years and consider it an appropriate choice for an educational gallery. Within the University we collectively study most facets of human life such as sociology and criminal justice, and expressive culture through arts and humanities relates to all of it. Part of what the Baron and Ellin Gordon Art Galleries regularly present is self-taught or folk and traditional art. Our Art from Guantánamo Bay exhibition will open days after the 20th anniversary of Guantánamo opening, a time when the detention camp and its detainees likely will be discussed in the news and other forums with increased frequency.

BD: Let’s take a look at the artistic dimensions of this exhibition including media, process, style, and training, e.g. To what materials do these artists have access? When, where, and how do they work? How would you characterize the range of styles? And what, if any, levels of formal training do they have?

CS: Detainees made art since arriving at Guantánamo with methods such as using their fingernails to draw on foam cups in which tea was served, and as far as we know, all “unofficial” art was discarded. In early 2009 after President Obama took office, the Joint Task Force Guantánamo announced a new art program to provide intellectual stimulation for detainees and to allow them to express creativity. At first they could make art only during the program and eventually were allowed to do so in their cells. There have always been strict rules regarding art supplies – detainees are given only a few types of soft, non-toxic materials like charcoal, acrylics, watercolors, and oil pastels, which could not be used to harm themselves or others. Restrictions on content have been less defined, and fluctuating over time. One former detainee reported that he was not allowed to draw or paint pieces with a political or ideological message, or that referenced camp security.

The range of work spans two- and three-dimensional pieces, with drawings, paintings, and sculpture. Some of it is very detail oriented while other pieces are more abstract. Detainees have received some instruction through the art program, and over time some such as Moath Al-Alwi who has been detained for over 19 years have continued practicing and making works such as ship models with increasing complexity from available materials including cardboard, t-shirts, prayer caps and beads, mops, and the plastic housing of shaving razors.

BD: In terms of content, will you share with us your insights into the range of subject matter represented in the show? I am curious about what common threads are woven through the work, if any, and whether the themes tend to be universal, personal, socio-political, or some of all? Additionally, are influences of other artists or artistic movements evident in the work?

CS: Drawing exercises have included color studies, still lives of fruit, and shading studies of vessels. The artists’ limited access to subject matter and dependence on their own memories and imaginations are reflected in the interior of a cell, an artist’s own foot, and an Arabic coffeepot brought in by an instructor. Memories and visions of home appear in symbolic portraits of missing family members as empty glasses, vacant seats, or uneaten fruit. There are visions of mosques and desert landscapes, as well as cities the artists wish to visit, depicted as inaccessible. There are dreams of starting a dairy or buffet restaurant, owning a car, and visiting the sea, which surrounds them but also remains inaccessible.

Abdualmalik (Alrahabi) Abud was detained for almost 15 years, and when he thought of his wife and daughter he would draw the complex architecture of Sana’a, Yemen in order to forget that he was imprisoned. Sabri Al Qurashi spent 14 years at Guantánamo and created peaceful landscapes and depictions of detainee life, along with political allusions like the Statue of Liberty wearing detainee constraints. Ahmed Rabbani has been detained for over 17 years, and his paintings of empty glasses and tables set for tea but with empty chairs and plates can be read as memories of his absent family and as references to his hunger strikes, undertaken to protest detainee conditions. Overall the works are less about artistic movements or influential artists and more about their experiences, memories, and hopes.

BD: What role do you feel the act of art-making plays in the lives of these detainees? Is it a result of the human need to express or is there also present a layer of political activism?

CS: Collectively the art reflects the needs to remember, forget, love, express emotion, dream, hope, and seek justice.

BD: What else should visitors to the exhibition know about these men, their art, and their lives?

CS: People can learn more by reading Mansoor Adayfi’s new memoir Don’t Forget Us Here: Lost and Found at Guantánamo along with Mohamedou Ould Slahi’s Guantánamo Diary, and view the film The Mauritanian about Slahi. Our innovative “MagicBox” is an interactive display case with a touchscreen allowing guests to explore multimedia content, and we use the device to show handwritten documents by Yemeni detainees in Arabic and English. Additionally people anywhere in the world can visit the exhibition to learn about the artists and their art via our telepresence robot, nicknamed “Gordon,” which can navigate the gallery, change height, and zoom in on art. Self-guided visits can be reserved weekly through ODUArtsTix.com. We will also announce public programming featuring former detainees on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, and we encourage following @oduarts to receive updates.

WANT TO SEE?

Art from Guantanamo Bay

January 21 through May 7

Gordon Galleries at ODU

odu.edu/gordongalleries, (757) 683-6271

Opening Reception: January 20, 2022, 6-8 p.m. (free and open to the public)