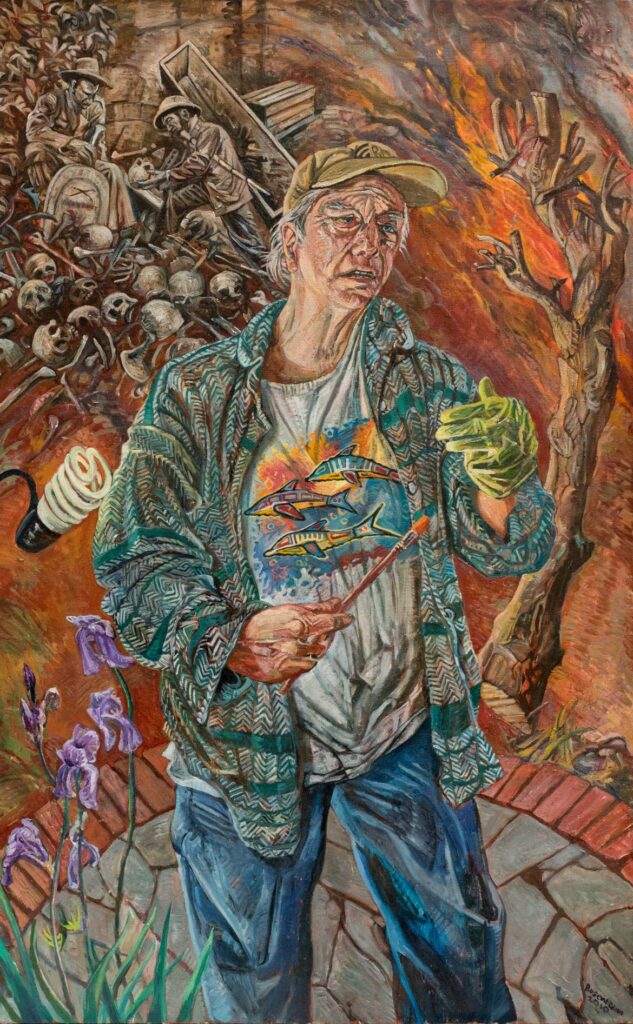

(Kent Knowles, Untitled)

By Jeff Maisey

The Linda Matney Gallery has unveiled an ambitiously engaging new exhibition thematically centered around the human psychological condition associated with emerging from a global pandemic and similar transformative experiences.

The Gallery describes the art shown in The Task That is the Toil as “emerging from a nightmare, dream, or the unconscious — literally hell in the quote it references.

The exhibition features numerous artists known within the scenes of Georgia, New York, California, Brazil, France, and Virginia. These include Art and Margo Rosenbaum, Scott Belville, Vanessa Briscoe Hay, Ryan Lytle, Kent Knowles, John Lee Matney, Sidney Rouse, Miles Cleveland Goodwin, Karen Allison, Jennifer Nagle Myers, Noah James Saunders, Len Jenkin, Eliot Dudik, Iris Wu, Glenn Shepard, Brian Freer, Richard Downs, Teddy Johnson, Merrilee Cleveland, T. J. Edwards, Linda Mitchell, Michael Ross, William Ruller, and others.

To help us wrap our heads around the scope of this exhibition I reached out to the Williamsburg-based gallery owner/curator John Lee Matney for the following interview.

VEER: Is The Task That is the Toil the largest group exhibition you’ve ever curated?

John Lee Matney: No, Art House at City Square/Temporal Distortions was larger in scope with multiple rooms. The Task That is the Toil combines smaller intimate works, some larger scale paintings and an installation by CNU’s Ryan Lytle entitled In the Shadows. This exhibit also reflects our new commitment to photography with works by William and Mary’s Eliot Dudik, Athens, Ga photographer Sidney Rouse, Glenn Shepard, an anthropologist from Virginia living in Brazil, and Iris Wu.

VEER: Are there challenges to exhibiting a group show verses presenting a single artist’s work?

Matney: Curatorially, I am looking at intersections that flow psychologically and in the space amongst varied works, which can actually be more compelling than what is possible

working with one artist because of limitations in one artist’s body of work at a particular time.

VEER: Are all of the exhibited artists ones you represent in “Task”?

Matney: The gallery represents all artists in the exhibition on the website and Artsy. Though some are in the early stages of representation, like wire artist Noah James Saunders. Scott Belville is showing for the first time at LMG in 8 years. California artist Richard Downs is making his local debut in the exhibit.

VEER: How did you decide the subject matter as a theme to curate “Task”?

Matney: I was thinking how resurfacing from the pandemic and the scars and awkward contents that emerge, and life not being quite the same again.

I looked at works that were mainly figurative and sometimes surrealistic, naturalistic, or expressionistic.

I like allegorical components that challenge the viewer to look at what could be mysterious or tenuous.

VEER: The show’s description regarding emerging from a pandemic is understandable. When you also include “or other challenges,” what exactly is being communicated and how do non-pandemic works fit within the show?

Matney: The Task That is the Toil came from a quote from Virgil’s Anead referenced in work by Carl Jung. Personally I think of the pandemic as akin in some ways with other psychological crises both collectively and individually. It has been nightmare from which we have been struggling to emerge that takes its toll on our consciousness. I have actually been thinking about an exhibition with this theme for some time. I found the quote very interesting in the early ‘90s when I was working in Athens and Atlanta and voraciously reading volumes in Jung’s Bollingen Series such as Mysterium Coniuntionis and Psychology and Alchemy and applying the ideas to my own photography and meditative practices. I wrote the quote on a blackboard in 1994 because it hit me so hard.

I was also thinking of Marie Louise von Franz’s Psychology of Fairytales and the concept she mentioned of the world above ground and below.

VEER: Which of these works were created specifically for this show?

Matney: None directly. I was conversing with many of the artists during the pandemic about what they were working on. I mentioned the exhibition to them, and all agreed they had works dealing with ideas that intersected with the theme.

Artists created some work during the pandemic, and others were created earlier. Teddy Johnson and I were in a dialogue about his Forest’s Edge seres and Glenn Shepard searched his recent archive for some appropriate works featuring the Baniwa and the Kayapo.

VEER: Let’s discuss Kent Knowles piece of the girl wearing a mask. Most of his paintings feature women, often in distress. Here we have a young woman with the signature sorrowed eyes his works are known for. As a representative of Kent’s work, how important is the consistency of characters or signature qualities when it comes to attracting serious art collectors?

Matney: I feel dynamic compositions, color, and storytelling set Knowles to work apart for collectors. Knowles works like Alto and Wayward come to mind. Alto featured a woman floating amidst animated flower petals that resemble butterflies. Oddly Knowles created the mask work mentioned in October 2019 before the pandemic. Knowles’s work “Cradle,” depicting a woman wearing green gloves holding a fawn on a windy day, is one of the standout works featured. Ironically, Art Rosenbaum’s Self Portrait with Philippine Graveyard also features a green glove. Knowles spoke reverently of Art in our recent Zoom event.

I can imagine collectors will see some intriguing parallels amongst paintings by Knowles and Rosenbaum in this exhibit.

Scott Belville, Rocking

VEER: Scott Belville’s “Rocking” does seem dream-like, maybe a reflection of childhood. The rack in the floor and tumbling cinderblocks seem symbolically important here. What is the work saying to the viewer or is it up to us to interpret?

Matney: It is up to the viewer to interpret. Belville says in his statement: “These recent paintings appear to have cracked open the door to the process of constructing their narratives. The paintings seem to be found ‘unfinished,’ in the context of the studio and sometimes even on easels in progress.” The trompe l’oeil troupe is used to activate possibilities in the narratives and give the viewer a faux role in the making. They are invited in to consider the context and the environmental predicament as they ponder the placement of the figures, meanings and the gravity of the situations at hand.”

VEER: Brian Freer’s “Lincoln” is an interesting portrait of the Civil War era president. Is the gray background symbolic of either the dreariness of the war or of the Southern uniforms?

Matney: Freer’s portrait of Lincoln is loosely based on a photograph taken by Alexander Gardner on November 15, 1863 just 4 days before his historic Gettysburg Address. The color palette is not so much deliberate, but subconscious. The gray background can be interpreted to signify the uniforms worn by the confederate soldiers as much as the grayness of a November sky. Lincoln’s skin tone is flat and pale suggesting his uneasiness and foreshadowing his death which was forewarned in a dream.

VEER: Does the red under Lincoln’s right eye have symbolic meaning?

Matney: The red, gray, and blue under his right eye symbolize what was at stake.

VEER: As a photographer yourself, what do you find interesting about Karen Allison’s photo of Mike Richmond of the band Love Tractor walking down the railroad track? Is it the graininess of the curved rail, in-focus coal, or Richmond’s gaze?

Matney: Richmond’s gaze and the trees and horizon beyond intrigued me; the entire image is somewhat out of focus due to very slight motion blur, which adds to a sense of mystery and venturing into the unknown.

VEER: One of my favorite photographs taken by you is of the late Jeremy Ayers. Can you share with us how you met Ayers in Athens and what was he like as a person?

Matney: One of the most prominent early memories of Jeremy Ayers was seeing him at a house party one day in the Athens in the mid ’80s. He was skipping around the yard with some other guests like someone in Alice in Wonderland in a top hat.

I would also see him out riding his bicycle with such a totally different persona that I didn’t recognize him at first. I would walk around with my camera, and I took his picture. I would also see him at the original Grit, which was more of an art gallery and tea room hangout than the current restaurant on Prince Ave. He would pop up at the table with a food item for which he would invent an unusual name referencing art or music — such as raw rutabaga with toothpicks he called the “Charles Ives Special.” Sometimes he had bongos around which he would casually play there.

I used to run into him a lot, and he would show up unexpectedly, including once way out of town on a property where I was living in Winterville. He was a very kind person, and he was sincerely interested in what I was doing and what my friends were doing with art; and he became more and more helpful and engaged with my work as the years progressed. I would often sit with him at outdoor cafes on College Square while doing street photography. He helped quite intensively around 1993/94 when I had a makeshift upstairs studio in a building downtown.

He would pose for me and bring some unusual characters in to be photographed. Around that time, I was thinking of new adventures, and he suggested I leave town for a while and that Athens would be more interesting when I returned, which turned out to be quite prophetic. Before I left, he invited me and some friends to participate as extras in a video for Vic Chesnutt’s Onion Soup. While I was away, I found out he had made paintings from some of my photographs for an exhibition. I came back for a one-person photography exhibition in 2003, and after that, he wrote back and forth with me, occasionally sending stories and interesting links until his death in 2016.

John Lee Matney, Shards: Portrait of Jeremy Ayers

VEER: How did you approach Ayers for this photograph and how did you compose it? What did you want it to communicate?

Matney: Ayers approached me actually. It was a shoot at his house with his friends Ane Diaz and Issac McCalla. This image was one of the last ones in the shoot, and I

acted a bit more aggressively in my direction to him. To me, he was almost looking down from a higher spiritual place, wondering about the challenges of the world or Athens at the time. The version presented in the exhibit was re-edited during the week of the attack on the capitol. Jeremy was always passionate about kindness toward all, preserving democracy and movements such as Occupy Wall Street. The image has been re-edited several times, originally when I was showing my work in Alexandria in the late 1990s, ironically referencing the capitol. Jeremy had me re-edit again, and this one is the third version.

The noise I added around the horse statute, and the American flag reflects how I felt during that chaotic week in January. Actually, during the shoot in 1994 conversation gravitated toward Grant Lee Buffalo’s Mighty Joe Moon, which I listened to again recently, and I feel it resonates a bit with some of my selections in this exhibit.

VEER: I love the colors of Len Jenkin’s paintings. They seem very nightmarish and bad dream-like. What do you see in Len’s work?

Matney: I see in Len a counterpoint to Art Rosenbaum. Len and Art were both students in New York in the early 1960s and spent time around Greenwich Village traveling in circles that intersected with Bob Dylan. Len is an accomplished fiction writer and playwright, and his paintings have a potency informed by his other talents but with self-taught and stream of consciousness qualities tapping into the collective subconscious.

VEER: Vanessa Briscoe Hay’s artwork also makes use of dramatic color. What story is this piece telling?

Matney: Vanessa made the piece from a dream she had after the sudden passing of the Athens poet John Seawright. A poem by Seawright and the story of the dream will accompany the piece. I would run into John quite frequently in the 1980s and ‘90s, and he would tell stories and tall tales and recite poetry. He was a fixture in the community who inspired many.

Art Rosenbaum, Self Portrait with Philippine Graveyard

VEER: Art and Margo Rosenbaum both have work in this show and they are simultaneously being shown at Virginia Wesleyan University’s Neil Britton Art Gallery. Is this a big deal for you as curator and representative of the Rosenbaum’s works?

Matney: Yes. To me, it is a culmination of a major effort as a gallery toward promoting Southern art in Virginia since 2012. I hope people will come to see Journeys and Neil Britton and Art and Margo’s works in Task and the other work. As a gallery, we don’t work with self-represented artists. We strive to break the silence with collectors looking to experience and acquire Southern art, whether they live locally or in the midwest, north, and elsewhere. The Rosenbaums’ work certainly has investment potential, and their significance as influential figures in the Athens art scene is clear. We have had conversations with collectors recently as far away as Berlin and London about works in the exhibition.

VEER: What other aspects from The Task that is the Toil should we expect? I hear there may be a music element midway through the exhibition’s viewing.

Matney: We are planning some mid-exhibition programming around music associated with Athens’ Armistead Wellford of Love Tractor as well as other event and zooms with artists and curators and gallery friends such as Chris Harris of Refuse Ordinary.

WANT TO GO?

The Task That is the Toil

Through November 14

Linda Matney Gallery

lindamatneygallery.com