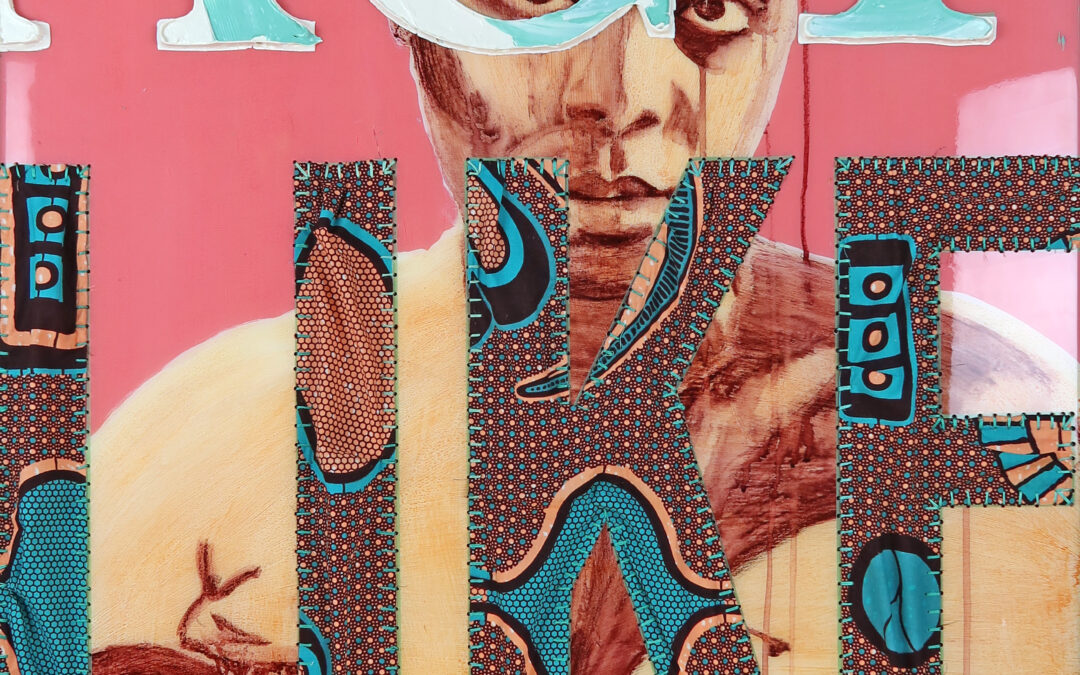

(April Bey, And I’m Calm, Calculated and Perfectly Aligned, 2020, Watercolor, drawing, acrylic paint, epoxy resin, hand-sewn African fabric, oil impasto, 40 x30 inches. Courtesy of the artist.)

By Betsy DiJulio

Virginia MOCA’s unabashed embrace of women-identifying artists during summer 2021 is steeped in aesthetics, politics, and culture, both within the museum world and within the so-called real world.

Ongoing discussions about an assertively female focus were formalized when statistics began emerging about how poorly women, especially mothers and women of color, were faring during the pandemic.

What emerged from those discussions were four overlapping, but distinct, exhibitions: one with a national/international scope, one with a regional reach, one featuring a local photographer, and one focusing on teen artists. Note, my preview tour did not include the latter two, Lauren Keim: Everyday Magic and Emergence: Teen Juried Exhibition which was not available for viewing at press time.

She Says: Women, Words, and Power

Artists: April Bey, Zoë Buckman, Lesley Dill, Meg Hitchcock, Cheryl Pope, Sandra Ramos, Hadieh Shafie, and Betty Tompkins

“Sticks and stones may break my bones, but words shall never hurt me,” is a familiar rhyme with roots as early as 1862 when it appeared in The Christian Recorder, a publication of the African Methodist Episcopal Church.

However, words can hurt. A lot. Written or spoken, long or short, words can sear to the bone. But they can also do just the opposite: they can save a life, change a life, change a mind, make up a mind, or make life worth living.

In She Says: Women, Words, and Power, eight women artists of different ages, ethnicities, and points in their careers use text in markedly different ways to create verbal and visual resonance around a host of issues. Their bodies of work have the capacity to expose hurt, to heal, and to heighten sensitivity to that which divides and collides.

Championship banners by Cheryl Pope welcome visitors to the exhibition. Born into a religious family with parents who were both coaches, Pope became a Chicago Golden Gloves Winner. But she also became attuned to patriarchy and, subsequently, to the space that writing allowed her to express what could not be said. Instead of heralding athletic prowess, Pope’s banners, created through a collaboration with teens in New York City, proclaim the preeminence of vulnerability and self-worth with phrases like “I Am Fearful,” and “I Encourage People.”

April Bey is a Bahamian-American artist who incorporates into her practice elements of Afro-Futurism, a celebration and projection of the contributions, innovations, and successes of global black cultures. Bey’s work centers around Atlantica, a fictional world in which power structures are reversed and with a parallel to her black father’s explanation of racism and colorism. In response to his young daughter’s questions, his narrative—that their family was from an alien planet sent to report on Earth—became both origin story and coping mechanism for Bey.

Her lavishly mixed-media work in unexpected and mouth-watering color palettes and textures functions as hybrid futuristic travel destination posters and protest placards. Painted portraits are overlaid with text such as “Act Like You Know,” “I will Not Comply,” and “Will Not Assimilate.” Key words of the phrases are cut out of Chinese knock-offs of West African fabrics and hand-sewn into the wood panels. In a postmodern art world example of Marshall McLuhan’s “the medium is the message,” the patterned fabric is a potent carrier of meaning, namely the impact of globalization and corporate capitalism on black communities.

Betty Tompkins’ Women Words installation created over more than a decade in the early 2000s and beyond is designed to be edited and reconfigured by curators. It functions as a kind of colorful wall-mounted slang dictionary of derogatory, objectifying and, at times, vile synonyms for women, e.g. “Broad;” their anatomy, e.g. “Bald Man in a Boat;” or their male-perceived proclivities, e.g. “Talk, Talk, Talk.” With words and phrases stenciled onto non-objective backgrounds painted on small canvases, the effect is brash and graffiti-like, but Tompkins asserts that she has never become desensitized to these insults and put-downs.

Zoë Buckman is always one step ahead of the viewer in this body of work in which she embroiders onto vintage linens text often related to gendered violence or its precursors, e.g. “She cries, he rolls his eyes.” Her handkerchiefs are rife with associations: staining, wiping away tears, domestic handicraft, and intimacy. Just when you think you “get” what she is doing, she changes the rules by, say, altering the direction of the font, letting loose threads dangle, inserting into the composition a precisely cut printed image of a snake, or any one of a number of delicately—and not so delicately—charged visual strategies. If this approach to montage and mixed-media sounds forced and contrived, it is not, though it is certainly curious and compelling.

Lesley Dill was previously represented at MOCA, then under a different moniker, by her poem dresses that feature the words of Emily Dickenson cut into the form of the empty, freestanding dress. In this exhibition, viewers are treated to a large wall-hung work entitled Eaters and Eaten in the Radiant Garden of Sorrow and Rapture. One component of a larger installation called Faith and the Devil, the images and spiraling words in fonts reminiscent of illuminated manuscripts and, possibly, newspapers summarize the installation’s themes: cruelty, violence, and lust alongside forgiveness, reflection, and transcendence. The mixed-media piece has been described as a “battlefield” of opposing forces, its spiraling mandala-like format a universal symbol of growth and change.

Meg Hitchcock’s contributions to the panoply are a series of small Illuminated Manuscripts. Though she stepped away from Christian Evangelism, she did not step away from spirituality or holy texts. The more she read, the more commonalities she found, describing the varied religions as “loosing their edges.” In this series, the letters meticulously cut from one holy book are reassembled to form the words of another in a meditative artistic practice. The accompanying paintings and drawings of repeating symbols like lotus blossoms and boxes are described by the artist as at once serious and playful.

Persian-American artist, Hadieh Shafie, has one foot firmly planted in modernism and the other just as firmly planted in postmodernism with it blurred boundaries and distinctions. Both of her pieces in this show take the shape of a circle—one arranged on the floor and one suspended from the ceiling—and are made up of individual scrolls, spirals of paper on which is written contemporary Persian poetry in fluid calligraphy. Though Shafie invites viewers to approach her work formally in appreciation of its shapes, its markmaking, and its color, for her the poetry was an early pathway to accepting her dual identity, for, as a young person, she had fled the Iranian Revolution with her family to Maryland. The scroll forms, with their vertical axial voids, are meant to evoke whirling dervishes who “turn on the axis of the heart” as they try to “empty” themselves of all distractions.

Note: At the time of my visit just prior to my press deadline, the artist’s books of Cuban artist, Sandra Ramos, was not yet installed.

Amplify

The concept for this exhibition is at least as compelling as the art in it. That is not to take anything away from the 19 women artists invited to participate nor from their work. Rather it is to say that the show’s conceptual underpinnings are as thoughtful and resonant—ripe for replication—as the compilation of art it undergirds.

Amplification is a gender bias-fighting tool dating from the early years of then President Obama’s first term when women staffers in this self-identifying “feminist” president’s inner circle did not feel heard in meetings. As reported by Juliet Eilperin in the Washington Post, it worked like this: if a woman made a key point, another would repeat it and credit or name the woman, thereby creating recognition and preventing a man from taking credit. Obama apparently began to notice and started calling on women more often.

Accepting of the fact that, during the Pandemic, there were no art fairs and no opportunities for gallery, museum, and studio visits, MOCA’s Alison Byrne and Heather Hakimzadeh decided to leverage that reality, reaching out digitally to some 70 of their women curatorial colleagues in DC, North Carolina, Maryland, and Virginia, asking them to “name” the women artists who they felt were deserving of “amplified” attention. Twenty-five responded and a roster of noteworthy artists was compiled, one that will be shared back to the curators, amplifying the process of “crediting” these women. From the roster, Byrne and Hakimzadeh selected 18 artists with a gender or identity focus for the show.

With disparate voices calling to each other across the galleries and amplifying what each other has to say, the show presents a web of themes and sub-themes that are the stuff of life in the 21st century. Through photography, painting, sculpture, sewing and textiles, among other media, these artists tackle activism, aging, anatomy, anger vs. hope, boundaries, the LGBTQIA+ community, roles, societal expectations, strength and vulnerability, whitewashing, and more. Hear them roar through October 24.

WANT TO SEE?

Summer of Women

July 17 through October 24

Virginia Museum of Contemporary Art

Summer of Women Public Programming

Guerrilla Girls: The Art of Behaving Badly

THURSDAY, AUGUST 5

6:30PM

FREE admission. Register to attend.

Artists and Curator Conversation: She Says: Women, Words, and Power Art

Thursday, September 23

6:30PM

FREE admission.