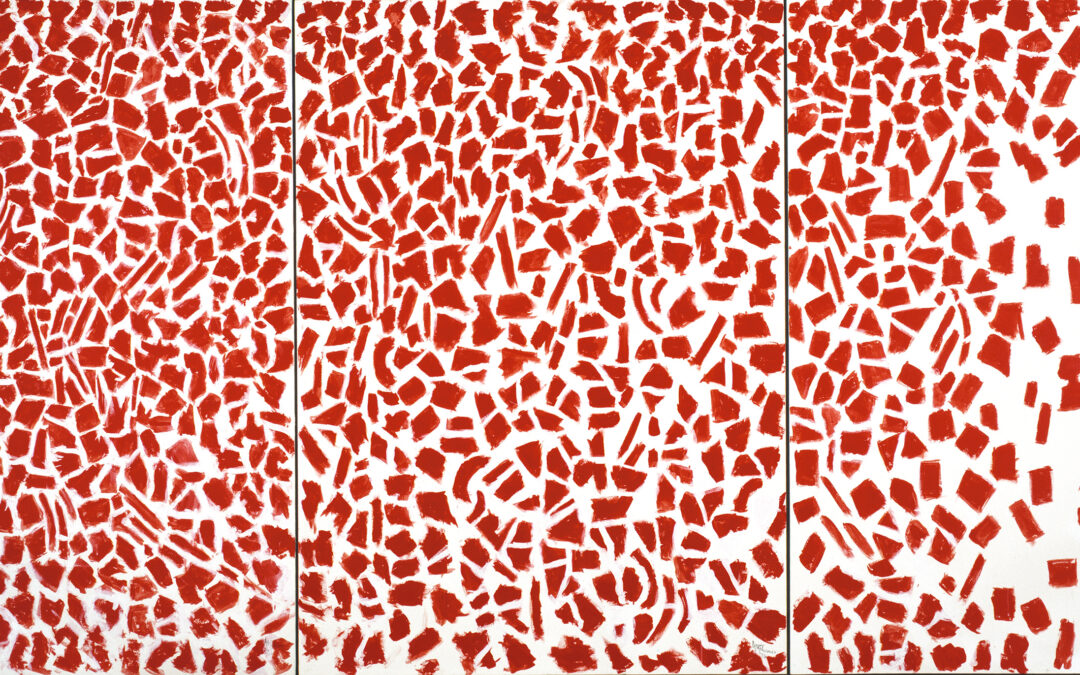

(Alma Thomas, Red Azaleas Singing and Dancing Rock and Roll Music)

By Betsy DiJulio

We have probably all said it: “That’s a Picassso,” or “That’s a Faith Ringgold.” But the work is not the artist and the artist is not the work. The work is the tip of the human iceberg, an artifact of a life as complex, conflicted and, at times, common as all the rest of ours.

And it is that fullness of human experience of the life of Alma Thomas that the Chrysler Museum, in partnership with The Columbus Museum in Columbus, GA, has thoughtfully constructed. Under the direction of co-curators Seth Feman, PhD, the Chrysler’s Deputy Director for Art & Interpretation and Curator of Photography, and Jonathan Frederick Walz, PhD, The Columbus Museum’s Director of Curatorial Affairs and Curator of American Art, this exhibition paints a more complete picture of an artist who is far more than the first African-American woman to have a solo show at the Whitney Museum.

The mythology that surrounds the 1972 “Whitney moment” in the life of Thomas (1891-1978) ignores some 80 years of her life before and after, from her childhood in Georgia to international acclaim. For those in search of a linear trajectory, a timeline at the entrance to the gallery provides just that. But in the rooms beyond, some six clear, but overlapping and crisscrossing, themes of Thomas’s life are organized in fluid, but distinct, physical spaces: The Whitney, The Studio, The Garden, The Stage, The Public Sphere, and The Field.

The show begins with a partial recreation of the Whitney retrospective: seven masterworks, as opposed to 14. Thomas, whose “Victorian mindset” coexisted with her fascination for “the new,” according to Feman, was captivated by space exploration as seen in major canvases in this gallery.

Moving deeper into the life and work of Thomas, we learn that Thomas’s home studio was in the kitchen of her D.C. rowhouse (her sister lived above) and looked out on her garden. Vignettes of objects that surrounded her, the stuff of daily domestic life, includes books, a Saarinen chair, her house dress, and African masks. Works on paper record her impressions of the natural world, rather than literal translations, which she then used to devise her signature patterns and iconic “Alma Stripes.”

Though Thomas was the first graduate of the Howard University art program, she had gone there to study design. Enthralled with the stage and a regular at the National Theatre, her costume designs are included, as are objects related to her teaching. Thomas taught for some 40 years, more than 30 of those at Shaw Junior High School, a school for black children prior to integration. Feman notes that her curriculum was innovative—and would probably still be considered so—as she developed a cross-curricular approach involving marionettes, which are on view. Following her retirement, she taught at her church, St. Luke’s Episcopal, a sacred place of “uplift” and community engagement for her.

As aspects of her life unfold, visitors are offered insight into the influence of the art of Europe, both realism and modernist abstraction. Something as seemingly unremarkable as the 1952 acquisition of a Cezanne painting by The Phillips Collection is said to have “shaken up the DC art scene” and impacted Thomas’s trajectory. The influence of her mentors, influencers, and collaborators, some of whose works are included, help fill out the narrative. Work by members of the Washington Color School, including Sam Gilliam and Morris Louis, reveal a kinship to Thomas, while highlighting her distinct voice within this chorus of color and joyful elegy to the edge.

The exhibition — featuring over 150 vibrant works — hits a concluding high note with a masterful triptych entitled Red Azaleas Singing and Dancing Rock and Roll Music. Completed in 1976 by the 5’1” Thomas in her kitchen as her hands were seizing up from arthritis and following a broken hip, the monumental painting almost seems to foreshadow the end of this artist’s earthly song. The directional force from left to right depicts the dissipation of her characteristic short strokes that, like leaves in the wind, are finally carried away.

Thriving in advanced age, as Feman notes, is one of the entry points and threads that is likely to resonate with visitors—along with civil rights, women’s history, gardening, theatre, education, and community engagement—even for those who may not be as passionate about art as some of the rest of us.

WANT TO SEE?

Alma W. Thomas: Everything is Beautiful

Through October 3

Chrysler Museum of Art