(Jowarnise Caston, Tangled Roots)

By Betsy DiJulio

George’s Floyd’s death last summer, the resulting Black Lives Matter (BLM) protests and counterprotests, and the aftermath, which continues to reverberate, have been the catalysts for all kinds of conversations between all kinds of people. Museums and their leadership have found themselves the targets of new levels of scrutiny related, especially, to bias. Other kinds of conversations, though, have centered around relevance; that is, how to become most meaningfully involved in the discussions and interactions swirling around and through the art world.

Work in Progress is the Hermitage Museum and Gardens’ answer to that question. The brainchild of Marketing and Exhibition Design Manager, Jennifer Lucy, the exhibition is an outgrowth of the staff’s conversations about how cities and artists have been responding to the intensification of social justice activism that continues to both bifurcate and unite factions of the population, as well as how to offer artists employment during a global pandemic.

For the last few years, murals have been having their day in the sun around the globe. Against the more recent backdrop of escalating social unrest, it seems that murals, with their particular ways of giving visual voice to social conscience, have a new raison d’etre. And so the concept for Work in Progress took shape.

Hermitage staff formed an advisory board of prolific, socially-minded artists to work with them to bring the exhibition to fruition. Selected were Hamilton Glass, founder of the Mending Walls project in Richmond; Dathan Kane, co-founder of the Contemporary Arts Network (CAN) in Newport News; Meme, founder of the Few & Far Women’s Collective; and Clayton Singleton, who VEER recently named “Mural Artist of the Year.” According to Lucy, CAN founders Asa Jackson and Hampton Boyer also provided invaluable insight.

Proposals arrived on Lucy’s desk in December 2020 in response to the advisory group’s call for entries. From that group, the advisory body chose 13 artists, many from the Hampton Roads and Richmond areas and some with global reach: Aimee Bruce, Jowarnise Caston, Gaia, Hamilton Glass, Emily Herr, Dathan Kane, Naomi McCavitt, Meme, Austin ‘Auz’ Miles, Nils Westergard, Navid Rahman, Clayton Singleton, and Shani Shih.

(Artist Hamilton Glass in the process of painting Untitled)

Though the BLM movement was a central catalyst for the show, the artists—some in collaboration with volunteers and local organizations—were invited to create work on topics of their choice which certainly included racism, but also homelessness, poverty, women’s equality, and mental health. Six murals are installed inside the museum—with two creating immersive experiences in entire galleries—and seven in the gardens.

One of the most engaging aspects of the exhibition—besides the work itself and the innovative public programming—is the broad interpretation of what a mural is. We tend to think of murals as paintings on the sides of commercial and public structures in urban areas, often used, as Lucy says, “to enliven communities on the edge of revitalization.” Sometimes decorative and design-based, they most often speak to the core values of the business, institution, or community; to their history; to their hopes and dreams; or to their abiding struggles and concerns.

At the Hermitage, three large free-standing murals join with four smaller ones mounted to the brick wall that lines the museum’s driveway. Inside, a blue monochromatic two-part mural by Nils in his signature drip style—an eye and a pair of hands holding a nail—flanks the entrance hall, but here is where the definition broadens. In the adjacent Great Hall, Gaia has created a “mural” in the form of a free-standing silhouette of William Sloane who, with his wife Florence, moved from New York to Norfolk to operate textile mills. They built the Hermitage in 1908 as a summer residence, but it soon became their primary residence.

Inspired in part by artist, Fred Wilson, and with income inequality his topic, Gaia—whose typical work might stretch eight stories tall—worked from old photographs to paint images of the Sloane children on the front and children who worked in the textile mills on the reverse. He filled the negative spaces with painted images from the Sloan’s travels as well as details of textiles. In the center, he cut a hole in the shape of Florence’s coat from 1890. From one vantage point in the gallery, the exhibited coat matches the size and shape of the cut-out exactly.

Upstairs, Naomi McCavitt’s corner mural is actually vinyl wallpaper installed to create a dramatic selfie booth. Through her studio, Design Thicket, she specializes in nature-inspired art and design with an environmental and social justice core. In Hampton Roads, she may be best known for her black-and-white botanical mural on the side of Prosperity Kitchen and Pantry in Virginia Beach. For the Hermitage, she has designed intricate black-on-white and white-on-black vintage-modern botanical wallpaper based on the Palolo Sea Worm, aka Moon Worm. According to Lucy, the worms are raised by the Kodi tribe on Sumba Island in Eastern Indonesia, adding that indigenous peoples protect a huge percentage of the world’s biodiversity. McCavitt is selling the wallpaper to raise money in support of the tribe’s efforts.

Occupying the same gallery is the work of Hamilton Glass: some 25 rectangular screen prints—plus an overspray pattern on the wall—that feature five different protest images from the 1960s printed in black over primary colors. The prints are intended to look like wheatpasted images that are peeling off the wall, thereby suggesting the impermanence of murals and street art, but also the repeating cycles of their themes of social justice.

In the two neighboring galleries, Dathan Kane and Meme have created immersive installations, though with strikingly divergent aesthetics and intent. Kane has covered every surface—and spilled out into the hallway—with a bold mid-mod-inspired black-and-white geometric design. Camouflaged throughout the space are circular mirrors and rectangular prints, which are for sale. Entitled Reflection 2020, the space is meant to be one in which you “reflect,” thereby confronting yourself, especially your responses to the upheaval of the last year and a half.

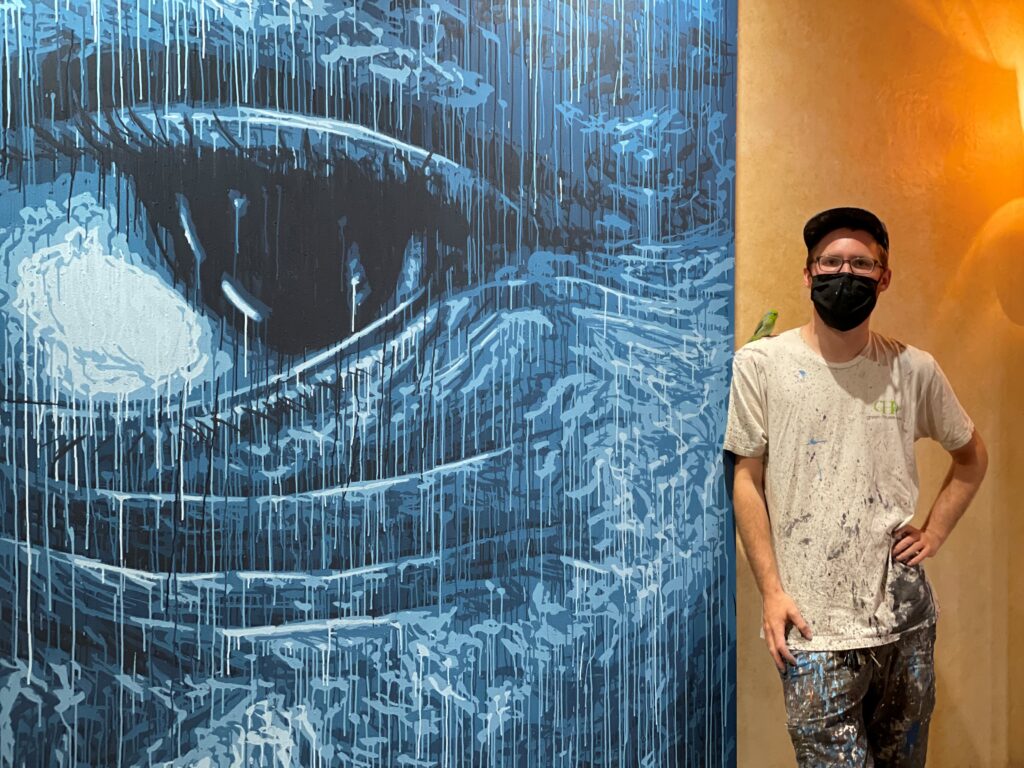

(Artist Nils Westergard poses with his green feathered assistant and Untitled)

As Lucy pointed out, Meme’s installation in the neighboring gallery is in part a statement about personal identity as a woman in the arts with a Burning Man vibe. Her dynamic tag activates one entire wall with the others painted in saturated tones of cinnabar, turmeric, and magenta. Textiles collected by the artist festoon the ceiling while cushions arranged casually on the floor create an inviting lounge-like space that feels urban, exotic, warm, and simultaneously relaxing and invigorating.

Of the seven more traditionally formatted murals outdoors, the three large ones were in progress on the day I visited with the other four to be installed at a later date. Emily Herr has partnered with the nonprofit For Kids which aims to end homelessness and poverty. A recent study listed Hampton Roads as one of ten locales in the U.S. with the highest eviction rates. Working in a pre-selected palette of pinks, yellows, oranges, and greens, volunteers painted images associated with home and safety across the surface. Five layers of imagery are planned with Herr “working her magic” at the conclusion of the volunteer painting sessions to bring it all together.

Austin “Auz” Miles pays homage to Norfolk waterways as passages through which people of color escaped slavery. Inspired by a book entitled The Water Dancer, Miles chose to depict a black female figure as a “conductor,” in reference to the Underground Railroad, who is part woman and part water. She is guiding and leading the way to out of slavery, including mental enslavement. Flying geese, a motif recontextualized from wayfinding quilts that marked safe houses in the Underground Railroad, soar in a northerly direction.

Like Herr, Clayton Singleton is working with volunteers to complete his police brutality-themed mural, Use Your Privilege. Directed by the artist, Singleton’s team will work over his underpainting in which he has chosen to change the narrative of his topic by depicting a black police officer enacting the violence. Text, reaching hands, and his signature Adinkra symbols are all painted in a primary color scheme plus black and white. According to Singleton, the symbol is called Bese Saka, a stylized representation of a “sack of cola nuts.” It symbolizes, among other things, power, togetherness, and unity.

WANT TO SEE?

Work in Progress: 13 Murals for Right Now

Through October 3

Hermitage Museum & Gardens