(Art Rosenbaum, Howard Finster with Couple and Fire)

By Betsy DiJulio

Art and Margo Rosenbaum have spent their careers and marriage traveling across different media and modes through various states of space and time. Trained and active in painting, they have, for over 50 years, documented the heritage of American roots music and folk culture through recordings, drawings and paintings, essays, and photographs.

These varied media have been compiled in books and box sets, including Art of Field Recording Vol I and II: Traditional Music Documented by Art Rosenbaum. Volume 1 of the set won a Grammy Award for Best Historical Album in 2008. Their varied practices intersect and complement each other, as both artists capture the identity of a nation as expressed through its musical and folk traditions and express their own personal preoccupations in their work.

The exhibition at the Linda Matney Gallery, Art and Margo Rosenbaum: Journeys in Art, Music, and Folklore, presents a rich overview of their collaborative and individual efforts, including Margo’s photographs and Art’s film and audio recordings that document roots musicians across the country alongside their expressive paintings and drawings.

Recently, I had the pleasure of interviewing Lee Matney and the Rosenbaums via email in a Question and Answer format. I encourage you to read all the way to the end, as this is one journey not to shortcut.

Betsy DiJulio: Lee, what is your connection to the Rosenbaums; that is, how did you learn about this remarkable couple’s collaborative journey?

Lee Matney: I was aware of the Rosenbaums as far back as the 1980s. Their work became more of a focus for me in 2010 when I opened the Linda Matney Gallery. Several of Art’s students were early exhibitors at the gallery and continue to be very influential to programs and projects here. Tyrus Lytton and I developed a project in 2013 featuring Art and 25 artists associated with Athens, Georgia.

BD: How does the Rosenbaum’s body of photographs, paintings, and recordings specifically fit into your vision, your gallery’s mission, and your personal interests?

LM: Having been a participant in the Athens, Georgia art scene in the 1980s myself, there is certainly some shared territory of experience. When Grace Elizabeth Hales’s Cool Town came out last year, Art was named as a central figure who influenced many and helped to bridge the gap amongst folk artists and musicians, academia, and the music scene that spawned REM and the B52s. Personally, Margo’s photography really strikes a chord as well because of my journey as a then shy, but passionate, photographer (one of my photographs of music scene founder, Jeremy Ayers, also appears in Cool Town). I was also heavily focused on old-time music in the 1980s and I would meet some of the archivists who would come through town. Many of the artists I knew were influenced by Pop, Performance Art, DADA, and Surrealism. Connecting with the Rosenbaums certainly shows another side of art in Athens that I was not as aware of earlier.

BD: From a curator/dealer’s perspective, Lee, where does the work of both Art and Margo fit into the context of contemporary drawing, painting, and photography? That is, from your perspective, into what genres does their work fall and what makes their work innovative, distinctive, and noteworthy?

LM: Art calls his work “Allegorical Figurative Painting” which is a style that has become a major focus of the gallery and our collectors over the last decade. There is a mystery to Art’s work exploring the complexities of experiences in the South that speaks to our collectors somewhat similarly to another painter we represent, Miles Cleveland Goodwin. Unlike Goodwin’s sparser style, Art’s work brings disparate elements together from various sources that give the viewer a lot to consider within the same composition. Multiple figures tell many stories within each painting: “There might be nudes, there might be objects, there might be a musician thinking about how what they are doing related to a kind of allegory.” Art plays with depth akin to works by the Mannerists and Cezanne. Looking at Rosenbaum reveals many different layers of meaning over a period of time. Margo’s self-taught style is another stream of interest at the gallery. Margo’s photographs of personalities and musicians are a new direction for us. Black and white documentary photographers such as Mary Ellen Mark come to mind when I see some of Margo’s work.

BD: What else do readers need to know about Art and Margo as people, as a couple, and as artists?

LM: I think that Art and Margo’s collaborative energy as artists really populates the gallery with rich layers of meaning that are rare in a single exhibit. Certainly, life and art are a labor of love for them in a way that creates a personal yet universal story.

BD: Art and Margo, as a married couple, whose life’s work has been so closely intertwined, will you share with VEER readers how you have defined your individual identities as artists while being two halves of an intense collaboration or is that even an issue for you? Did and do you maintain individual practices that have little to do with each other or has the shared work been the real thrust of your artistic lives and partnership?

Art Rosenbaum: To the last part of your question, I don’t think it’s a dichotomy. More like the line from the blues: “two trains running, running side by side.” When we met in New York in 1965, we were already deeply into our art pursuits: I had painted since I was a kid, had studied with John Heliker at Columbia, was back from a Fulbright in Paris, and was living and working in a loft. Margo had studied with Richard Diebenkorn, and was also living and working in a loft. As painters we have continued our work to this day, and look at, argue about, and hope we inspire each other’s work.

Back when we met, we discovered that we also shared an interest in folk music. I had already been collecting and documenting traditional music—as well as playing it—so Margo gradually became more involved with photographing. She became a serious photographer when I was teaching at the University of Iowa in the 60s and, hence, her photographic work became an integral part of the recordings, books, and exhibitions that grew out of our visits to traditional musicians and singers. Some of what we do is a joint venture; some is more searching for our own images and voices.

I’ll add that especially during the years when we were developing Folk Visions and Voices—a traveling exhibition, book, recordings, and videos all based on our encounter with Georgia traditional music—lots of people saw Margo mainly as a photographer of rural musicians and me as a painter and charcoal artist looking at the same subjects. All the while I was doing allegorical paintings, some referring in part to the musicians, some not; and Margo was photographing and painting all kinds of other subjects.

BD: Do you see your drawings, paintings, photography, films, and recordings as somewhat discreet endeavors or is it more a case of, as my artist friend would say, living the “art life” in which it is all a cohesive, interconnected flow?

Margo Rosenbaum: As art said, some of our work is highly personal, some strives to be more “objective,” if that is possible. All of it does, of necessity, become part of an “art life;” as artists, that’s who we are.

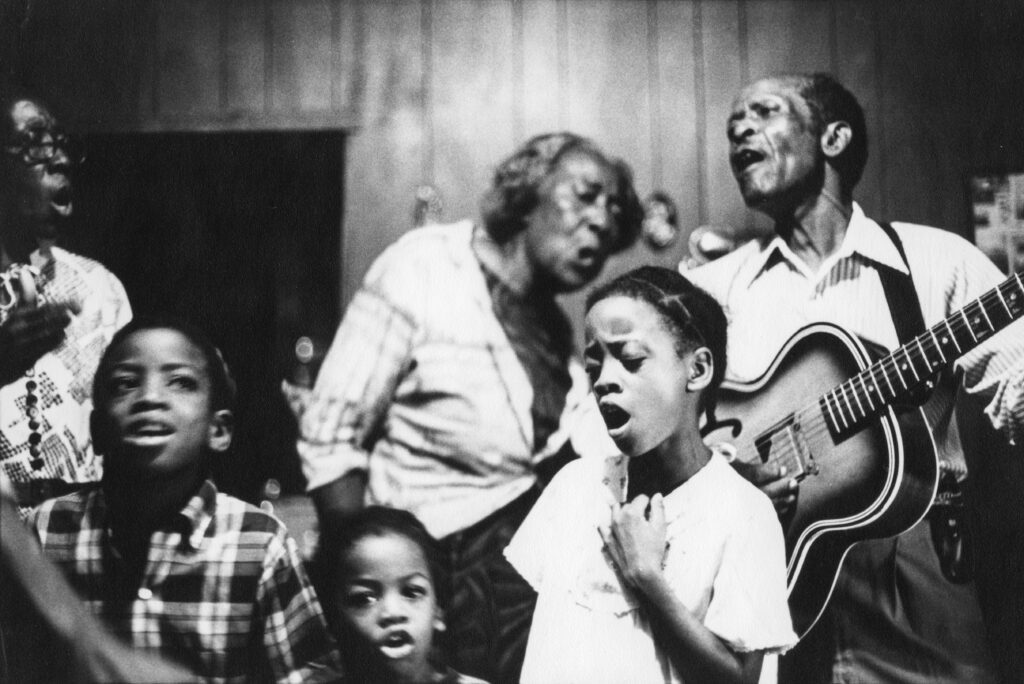

(Margo Rosenbaum, Doc and Lucy Barnes with Mavis Moon and Children)

BD: Do you see a distinction between so-called “fine art photography” and “documentary” photography and, either way, will you explain?

MR: Oh, I don’t know. I chose the title Drawing with Light for my new book of photographs which presents a flow of diverse images that I hope blends together these two notions.

BD: As your collaborative work progressed and continues, who “drives” and who “steers” in terms of the directions you take, both literally and figuratively?

MR: We both have input and ideas. Once when an interviewer asked what it’s like to work with Art, I said “holy hell.” I have a more positive thing to say: for something to be of any worth, there are bound to be rough spots on the road, but we try to deal with them.

AR: We bring different things to what you describe as the collaborative part of what we do. I am pretty good at seeking out interesting musicians: ballad singers, blues musicians, fiddlers, and know the basics of field recording. I can write pretty well. I do most of the driving (the car, not the “driving” of your question). Margo is good with people; feels comfortable with folks from very different backgrounds from hers. She has proposed projects and exhibitions: she first suggested to The University of Georgia Press that they do a book drawn from the field collecting we’d done in Georgia. She is good at selecting work for exhibitions and publications and at arranging and “spotting” exhibitions.

BD: Art, I know you are a musician, but from where do your musical roots come and, by the same token, to what do you owe your interest in “roots music”? Margo, how would you describe your relationship with music?

MR: I have been interested in music since I was a child, but was somehow attracted to traditional music. I took guitar lessons from Bess Lomax Hawes at UCLA and hung out at the Ash Grove in LA during the early “folk revival.” Art taught me banjo and I enjoy playing old-time music with him and with friends. I like different kinds of music, but traditional folk music gets my juices going.

AR: Lots to say; I’ll make it short. My parents liked music, mainly classical, and my brother Victor is a world-class pianist. But I heard my grandmother sing Yiddish songs, and my father sang to me street ditties he learned on Paterson New Jersey stoops with his friends as a kid. Thus, I learned that music can be homemade and informal. I listened to records like Burl Ives, the old 78s on the Harry Smith Anthology of American Folk Music, Lomax field recordings, and Pete Seeger who became my banjo hero, and whose records and books helped me get started on my main instrument, the five-string banjo. Pete also said at a concert, “don’t listen to me, listen to the folks I learned from.” For me this was hanging out in Michigan migrant farm worker camps near where I worked in a hotel as my summer job when I was a student, meeting Black blues musicians like Scrapper Blackwell in my home town of Indianapolis, going down to East Kentucky to seek out fiddlers and banjo players; later meeting the last ring shout community in Georgia, and recording ballad singers May Lomax and her sister Bonnie Loggins in North Georgia. Along the way I became known as a performer, documenter, and author of books on banjo styles. I love singing sea chanteys, which have become “in” of late. Mainly I am driven by an affinity for the directness, humor, sadness, and passion of “trad” music. I am using that term, as they do in Ireland, because the meanings of “folk” and “roots” have become hopelessly blurred.

BD: Art, as an art professor emeritus at the University of Georgia, what do you feel it is most essential to teach art students about both the artist’s craft and the artist’s journey?

AR: I try to impart some of what I know, have learned, am continuing to learn. I like teaching specifics like painting materials and artistic anatomy. I like to share personal experiences and anecdotes, the lore of the endeavor! I tell them there are no guarantees in “the art life,” that it can be difficult. I gripe about some terms that I seldom heard or used during my student days: “studio visit,” “artist’s statement,” “career.” I understand that especially now things are difficult for an artist starting out, that Albert Pinkham Ryder’s dictum about not doing art to live but living for art can seem hopelessly romantic; but there is something deep and meaningful about the art life. I also mention two former UGA painting BFAs who are now successful lawyers but have kept their art as a crucial part of their lives.

BD: Is there anything else you would like to share about your lives and work?

AR: I should mention that our son, Neil, has been a large part of the project we’ve been talking about. He tagged along on field trips as a youngster, met some interesting old-timers, studied, and became a videographer. He filmed and edited a feature-length documentary, Sing My Troubles By: Visits with Georgia Women Carrying Their Musical Traditions into the 21st Century. I hope artist Daniel Barber’s comments on Neil’s film reflect what the three of us have tried to do: “This film casts a subtle and complex light upon people and ways of living too often generalized about and fuels a strange kind of love of life and art.”

MR: So far it’s been a good trip.

WANT TO SEE?

Art Rosenbaum and Margo Newmark Rosenbaum: Journeys in Art, Music, and Folklore

Linda Matney Gallery

Through March 31

Linda Matney Gallery

5435 Richmond Road, Suite A, Williamsburg

lindamatneygallery.com, 757.675.6627