By Tench Phillips, Naro Cinema

I like to do my writing in the mornings when I feel most clear-headed. I sit with my laptop accompanied by my cats and a hot cup of black coffee. My daily java ‘jones’ requires freshly ground French dark roast beans placed in our manual pour-over Chemex drip-through coffee system. I depend on this morning ritual to kick my mind back into gear, to elevate my mood, and aid my morning constitutional.

My coffee habit has strong social approval – so it’s not really an addiction, right? Well, not according to one of my favorite non-fiction authors, Michael Pollan (How To Change Your Mind). He would beg to differ in his new audio book, Caffeine: How Coffee and Tea Created the Modern World. He cites caffeine as “the most-used drug in the world”. And to confirm its potency, he advocates going cold-turkey with one’s coffee habit, just to experience the intensity of withdrawal, and to rediscover one’s normal baseline.

Besides coffee, which food substances are considered the most habit forming? We would add sugar, chocolate, cheeses, starches, and some spices to the mix. Empires have been built upon some of these food crops. Plantations that were first established in the Americas during the 17th century expanded the injustices and cruelty of European colonialism and exploited the African slave trade.

In our modern day consumer culture, the food industry has designed their addictive junk foods with just the right mix of ingredients to seduce our palate with inexpensive and nutritionally worthless foods. Corporate marketing savvy knows no limits, and preys on the young and the vulnerable by cultivating customer loyalty. Are you a Pepsi or Coke person?

And then there are the psychoactive plant alkaloids that society identifies as drugs. They occur naturally in such botanicals as coca, opium, tobacco, cacti, mushrooms, and poisonous plants. These plant-based alkaloids are diverse nitrogen molecules that fit hand-in-glove within our endogenous neuroreceptors. Many of these alkaloids are best tolerated as medicines when consumed in their natural plant form as indigenous people have done for eons. It’s only when these plant alkaloids are refined, concentrated, and synthesized into street drugs, that addiction and toxicity may occur at higher dosages.

Substances with the most addictive potential include tobacco, alcohol, cannabis, painkillers, opiates, cocaine, sleeping pills, stimulants, and tranquilizers. Nonetheless, casual indulgence, even of heroin, does not necessarily lead to addiction. But some people are more susceptible to become dependent than others. Contributing factors may include the user’s particular biochemistry along with their predisposition based upon a history of personal stress, social defeat, childhood neglect, or abuse during early brain development.

There is a growing movement that includes LEAP (Law Enforcement Action Partnership) advocating for the legalization and regulation of all drugs, regardless of their addictive properties. The movement’s goal is to gain control over the lucrative and corrupt blackmarket and to transform society’s recognition of drug abuse as a criminal problem to be adjudicated within an unjust legal system to that of a health issue that is to be treated in rehabilitation programs. Much can be learned about such a cultural transformation from Portugal’s program of drug legalization, and the societal benefits it has brought.

If politicians were really concerned with reducing the massive number of deaths from heroin overdoses due to sketchy street drugs laced with fentanyl and other lethal additives, they would legalize heroin and regulate the market in ways similar to the regulation of legal cannabis in a dozen states. But such efforts have always been stymied by the unholy coalition of black market profiteers, law enforcement, and the private prison industry. These forces are not willing to surrender the obscene blackmarket profits reaped by prohibition that keeps the drug trade illegal.

Younger people who are aware of such social injustices as economic inequality, poverty, and racism, know that these are the causal roots of addiction. They also feel resigned to a system that shuts them out, and leaves them disempowered and disenfranchised. The political establishment’s deception and utter inability to address our multiple social and environmental crises, has precipitated a nihilistic resignation and despair for many youths who self-medicate to deaden their pain.

In addition to substance abuse, our behavioral dependencies have been exacerbated in our modern era. Technology and the internet have increased our consumption of news, information and entertainment, and our connectivity to our social networks. The illusion of freedom and control that cyberspace provides us is difficult to turn off and power-down. Although we know that our privacy has been compromised, it’s not a big concern for most of us. The tech monopolies know our habits and desires, and target our weaknesses to capture and control our attention. And so, we compromise so as to accommodate this brave new world of personal web marketing.

How did we end up like this? We live our lives hunched over our phones and computer screens, alienated from real world interactions. We are having our brains programmed by businesses that cater to our immediate pleasures but that can cause much harm in the long run. Anti-social behavior has become socially accepted and may include compulsive gaming, compulsive shopping, social networking, cyber-sexual consumption, gambling, stock market investment obsession, and all kind of numbing distractions.

We live in a culture whose founding principles reflect the values of liberalism – progress, liberty, reason, along with the pursuit of happiness. Those ideals have been turned upside down by corporations that prey on our biological pleasure centers and coerce us to consume and think in ways that may harm ourselves and our fellow citizens. The broader adverse effects of modern corporate-dominated life are widespread – isolation, social alienation, loneliness, lack of purpose, and loss of meaning.

In social scientist’s David Courtwright’s new book, The Age of Addiction: How Bad Habits Became Big Business, he chronicles the triumph of what he calls “limbic capitalism,” the targeting by business of the brain pathways responsible for feeling, motivation, and long-term memory. He argues that we are in dire need of learning how to resist the temptations of technologies that are intentionally rewiring our brains.

To liberate ourselves from the stranglehold of surveillance capitalism, we must first have a better understanding of the global enterprise that exploits our bad habits. Courtwright explains that as capitalism has cultivated and awarded more pleasure, consumers have received more benefits. But in so doing, we have compromised our autonomy and increased the potential for more addictions. There has never been a people whose survival is more dependent on business and government than 21st century Americans.

The whole predatory system is enough to bring you down. And indeed it does. Americans are depressed like never before, and are taking beaucoup amounts of anti-depressants to be able to proceed on the treadmills of their lives. In fact, one in six of us over the age of twelve is currently being prescribed psychiatric drugs – defined to include anti-depressants, anti-anxiety drugs, sedatives, sleeping pills, and anti-psychotic drugs. Although these drugs may benefit some people in the short-term, there are detrimental side-effects and health issues that manifest over the long-term.

At least that’s the argument recently laid out in Lauren Slater’s personal memoir and investigative journal, Blue Dreams: The Science and Story of the Drugs That Change Our Minds. She describes the lineage of medical treatments used for depression as progressing from legal morphine, to barbiturates, lithium, electroconvulsive therapy, tricyclics, Prozac, and next-generation anti-depressants.

Prozac is marketed as a site-specific drug in the class of selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI). These type of drugs are given a special status in medicine, even though it’s not really understood how or why they work. They are to be taken every day, with the intentional goal of dependency and a daily habit. And yet, they are not identified or perceived as addictive substances. And the pharmaceutical companies can market them directly to the public, fulfilling their corporate commitment to deliver handsome profits to the investor class.

And how well do SSRIs work? It turns out, not well at all for mild depression. For moderate or severe depression, 40 to 60% of patients using anti-depressants noticed an improvement of symptoms within six to eight weeks. But in the same study, 20 to 40% of people taking a placebo also had improved symptoms over the same period of time. It seems like these drugs have been over-praised and over-prescribed.

In Blue Dreams, Lauren Slater goes on to advocate for psychedelic therapy as a better option for depression and addiction. Back in the early ‘70s, synthesized LSD and DMT-containing substances like psilocybin, ayahuasca, and peyote were criminalized and designated as Schedule I drugs by the federal government, a category shared with cannabis and heroin. All of these unrelated psychoactive substances were declared to have no redeemable social value nor any medical benefit. After being declared illegal, the subsequent War On Drugs has resulted in the mass-incarceration of millions of primarily poor minorities for participation in the black market. This racial injustice has eroded citizen trust in law enforcement and the unjust judicial system. And prohibition hasn’t worked. Street drugs have only become more prevalent over the last fifty years.

One of the distinctions made between addictive drugs and plant medicine or psychedelics is that people use drugs to numb their emotional or physical pain, and “check out.” Whereas mind-expanding substances awaken one to their fixed thought patterns and sense of self. The plant medicines perform as dehabitualizers. Our ordinary consciousness is disrupted, and the ego shifts from the foreground to the background. Many people experience a profound opening of the heart into an expansive field of loving awareness.

The taking of entheogens – the term means “becoming divine within” – is not easy for most people. It requires hard work to stay centered, as well as courage and trust to face primal fears and go through difficult passages. But there are substantial gifts waiting after going through “the squeeze”. The insights gained through non-ordinary states may provide the inner revelations necessary to understand the root causes of one’s addiction. But to make long-lasting changes in one’s thoughts and behavior, a strong conviction and a supportive community are essential.

Lauren Slater sees psychedelic therapy as a truly novel approach for treating addiction and depression. She goes on to explain, “The beauty of them is you can take them just once or twice. You get a significant mind shift from that. That’s what you’re trying to do in psychotherapy. You’re trying to shift a person’s paradigm, or a person’s narrative they believe about their life.”

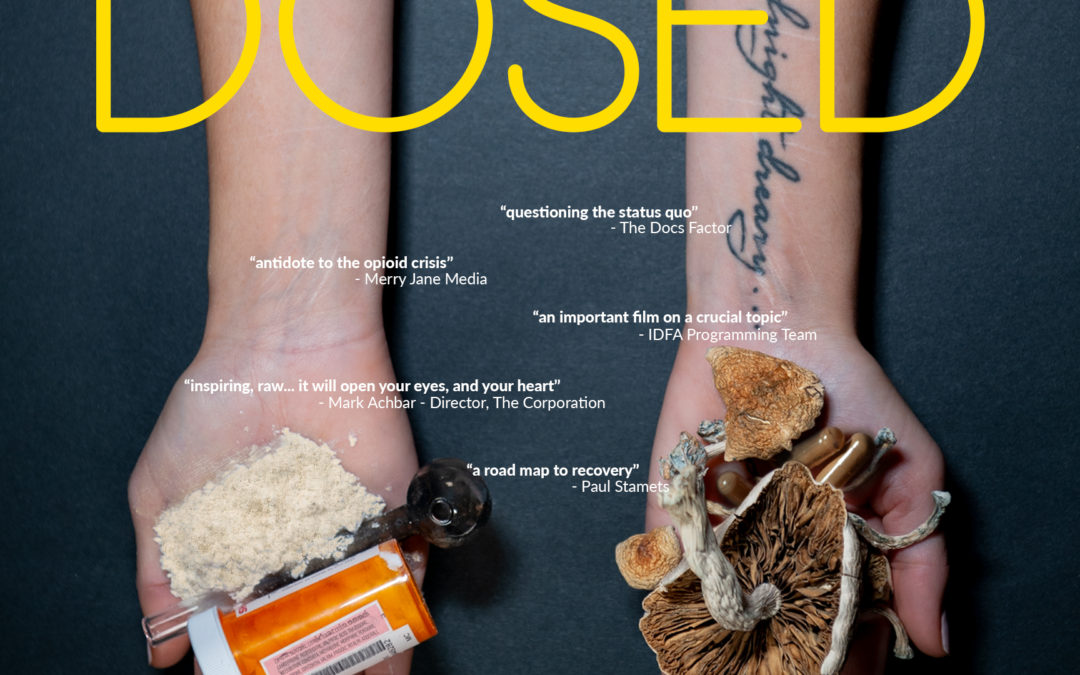

The new documentary Dosed is a personal story about the severe addictive habit of the film’s protagonist, Adrianne, a friend of filmmaker Tyler Chandler, who is unable to kick her severe heroin and methadone habits. Desperately addicted and contemplating suicide, she submits to experiencing multiple sessions of shamanic plant medicines such as psilocybin mushrooms and African ibogaine in her quest for healing.

This film is a Canadian production and takes place around Vancouver where there are many addicts who live on the streets. The Canadian government allows for licensed rehab centers to use more unorthodox measures for detox that may include psychedelics in the quest for inner healing. Adrianne allowed for the intimate filming of her raw emotions during therapeutic sessions and during recovery, as well as documenting her downward relapses as she repeatedly falls back into her habit.

Appearing in the film are renowned addiction therapists and advocates for psychedelic therapy such as Gabor Mate and Mark Hadden, mycologist Paul Stamets, and Rick Doblin, the director of the advocacy non-profit, MAPS. Doblin’s organization has worked ceaselessly over the years for government approval of psychedelic and cannabis programs for the treatment of addiction, depression, PTSD, and end-of-life distress suffered by cancer patients. There are ongoing studies at such medical universities as John Hopkins that are being funded by MAPS. Due to the success of these programs, Doblin predicts that medical psilocybin and MDMA will finally receive legal status for psychedelic-assisted therapy by 2021.

Tom Crockett, a long-time friend of the Naro Expanded Cinema in Norfolk, is an artist, author, teacher, and works with at-risk youth as the executive director of the Together We Can Foundation. He is the author of The Artist Inside: A Spiritual Guide to Cultivating Your Creative Self, and Stone Age Wisdom: The Healing Principles of Shamanism, and One Drop Awareness: Picturing Enlightenment and Nonduality.

Tom has critiqued Dosed as follows, “So much of this film rings true for me. Working with plant spirit medicine is about so much more than replacing one kind of western medicine with another kind of medicine. It isn’t a quick fix… the team supporting her mentions that about 50% of the effectiveness is from the plants and 50% from the talk/ceremony/support team/protocol.”

Traditional treatment programs for severe addiction result in variable success rates for recovery, and run the gamut from rehab centers, methadone centers, psychotherapy, and the numerous 12 step programs. The decision to enter a recovery program may begin with the realization of the self-deception that one perpetuates in justifying addictive behavior, and that the mind cannot heal itself. The major obstacle to recovery may simply be the fear of giving up all of our excuses and our self-loathing. The important component of an effective program is a social support group that nourishes and supports the individual’s recovery. All of us are in need of such an empathetic social network.

We are all substance users, and abusers. That’s what human beings do – we consume nutrients and air that is converted by complex biochemical processes into stored energy that is used for our body functions. All of these chemical substances we take in change our metabolism and alter our consciousness. We must learn to discriminate which chemical substances in the physical environment are healthy to consume – and which messages in our mental environment are worthy of our attention. We can align our lives with our innate ideals to connect, to love, and to serve.

Could an addictive society ever go cold turkey? We cling to our conveniences and pleasures, well-knowing that our habits are bringing our biosphere to the brink of collapse. Unregulated business under free market government policies have propelled the rapid decline in the health of our planet and of ourselves. It’s crucial for us to acknowledge the social injustice of our economic system, along with our inability to heal ourselves without making fundamental changes in the ways that we govern. It’s time for ‘Our Revolution.’