(Writer Jerome Langston with WHRO’s Lisa Godley from the stage at the Attucks.)

By Jerome Langston

On this unseasonably warm, mid-week day, there is little activity happening outside of Norfolk’s historic Attucks Theatre, the performing arts venue famously situated at the corner of Church Street and Virginia Beach Boulevard. That is also the case inside of the stately theatre―a meticulously designed, quiet marvel of architectural excellence that is ornate, yet quite beautiful in its subtlety―which is celebrating its grand centennial this year.

Of course it’s only in the early afternoon, and on a Wednesday at that—so the fact that only Denise Christian is here―to guide me through the theatre, and help set up a place for my interview with WHRO’s Emmy-winning producer, Lisa Godley, is completely understandable. Denise and I rarely get to see each other, but we go way back to like 2004, when I first started writing for Port Folio Weekly, and she was still the project manager for the Attucks Theatre Renovation Project.

Lisa arrives to the theatre alone, with her considerable height and lovely demeanor, gracefully carrying around the weight of high expectations for her latest works. In just two days, the Attucks will fittingly host the premiere screening of the WHRO documentary, The Historic Attucks Theatre: The Apollo of the South, which is a co-production with the City of Norfolk. Lisa is the doc’s producer, writer and narrator—though she’s quick to admit that “it takes a village.” The half-hour documentary also airs multiple times this month on WHRO, our local PBS station.

And then there is her work on WHRV’s Another View, the weekly radio talk show hosted by Barbara Hamm Lee that covers local and national news from an African-American perspective. Lisa co-produces the show, and will host it this Friday in the wake of the disturbing controversies that have embattled Virginia’s governor, lieutenant governor, and attorney general.

We put that aside though to talk about the documentary―while sitting on the theatre’s stage―and how important the Attucks was to Norfolk’s African-American community, back in the day.

“I think it was the heart of Church Street,” Lisa says. “People like the former vice-mayor, Herbert Collins―we found one of those interviews with him from Gone But Not Forgotten, and he talks about how watching these entertainers, walk up and down Church Street, eat at restaurants on Church Street, stay at hotels…and then perform right here at the Attucks―how that made him know that there was more to life than what they had been exposed to.”

The documentary, which Lisa and her team worked on last year, with input from the city and members of the Attucks Theatre Centennial Commission, tells the history of the Norfolk theatre through pictures, interviews, old video clips, and music. “You will see a lot of archival footage,” she says.

The Hampton Roads native also says that she learned a lot of rarely known facts about the Attucks Theatre, while conducting research for the documentary. One notable fact is that in spite of the Attucks being popularly referred to throughout the years as the “Apollo of the South,” the Attucks was actually operating as a highly successful, black performing arts theatre in the 1920s, attracting major black entertainers like Cab Calloway and Bessie Smith, years before Harlem’s Apollo Theater did. “The Attucks Theatre was bringing in these quality entertainers, years before the Apollo brought in these entertainers,” adds Lisa.

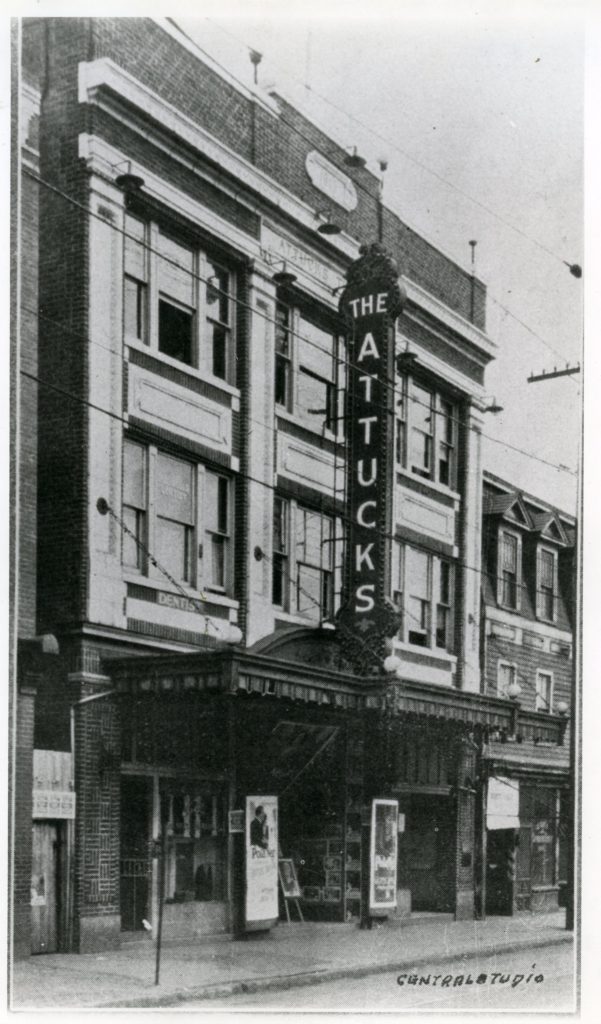

(Attucks Theatre, circa 1927. Photo from Slover Memorial collection.)

The Attucks Theatre documentary is part of Norfolk’s year-long commemoration of the famed theatre’s 100 years of existence―a full century that saw it open in 1919, close in the fifties, become a men’s clothing store for a time, receive official designation as a historic landmark, and eventually, after a successful restoration campaign―re-open in 2004. The Attucks is further distinguished by the fact that it’s the only remaining U.S. theater that was financed, designed and built by African-Americans.

Upcoming Attucks 100 programming includes a performance by the Elbert Watson Dance Company on February 23rd, a concert by vocalists Lawrence Brownlee & Eric Owens on March 3rd, the continuation of the Church Street Jazz series, and Saturday Night Live comedian and actress, Leslie Jones, in concert on April 20th.

And then there’s Tarell Alvin McCraney’s Choir Boy, an enthralling musical drama being produced by the NSU Theatre Company, which plays at the Attucks from February 15-17. Tarell won an Academy Award for Moonlight in 2017, which has increased interest in his acclaimed work as a playwright. When I talked earlier this week to Anthony Stockard, the producing artistic director for NSU Theatre Company, his cast and creative team were deep in rehearsals for the play. Anthony is also a member of the Attucks 100 commission.

“Mayor Alexander knew that he wanted a commission formed to observe the centennial,” Anthony tells me, early in our phone conversation. “It’s a considerable landmark―a sign of innovation and resilience―and the power that communities have to create the world they want to live in.”

Anthony chose Choir Boy for the Attucks commemoration, in part because the play incorporates the singing of spirituals, which is at the root of American black music, and has long been showcased at the Attucks Theatre. “You always want to match a show to an appropriate space, and this definitely was that. And I felt like it’s something that is connected to all of what we’re celebrating this year, with the Attucks.”

It is very difficult to overstate how remarkable an achievement it was, for a group of local African-American men, businessmen who formed the Twin Cities Amusement Corporation, to obtain funding for, and eventually open a then state of the art theatre―in 1919. This was a time of deplorable racial segregation in the south, segregation that would become law―impacting housing and public spaces―in the 1920s.

The Attucks Theatre was named for American patriot Crispus Attucks, the first person killed in the American Revolution, during the Boston Massacre of 1770. Attucks was a man of African and Native American ancestry, and is historically regarded as an African-American hero.

The ambitious theatre was designed by a young, African-American architect, Harvey N. Johnson, a Richmond native who also handled the design and renovation of a number of Norfolk’s prominent churches, including First Baptist Church Bute Street. The Attucks didn’t just have the 600-seat theater portion, with its balconies and orchestra pit―the building also included significant office spaces— for use by Norfolk’s black professional class.

Initially used as a movie house, the first act to perform in the theatre was The Lafayette Players of New York, in their production of It Happened in Harlem, on October 5th, 1920. Soon after, many of the top African-American performers of that era, including Virginia’s own Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington, Nat King Cole, Dinah Washington and so many others, performed at the Attucks—often staying with local black residents till the eventual construction of hotels, like the Plaza Hotel, owned by Church Street business legend, Bonnie McEachin.

The theatre was later renamed the Booker T in 1933—still showing movies, and hosting talent shows and major concerts. The name was changed, though, to “honor a more recent hero,” explains Denise Christian, shortly after my interview with Lisa Godley. In her work as project manager for the ten-year long restoration campaign for the Attucks Theatre, Denise has become an Attucks Theatre history scholar.

“Many of the performers like Ruth Brown and Gary U.S. Bonds, both of whom are covered in the documentary, talked about the fact that when they performed here, it was the Booker T,” says Denise. Nevertheless, after many years of laudable success, the theatre closed in 1953. Stark & Legum bought the building in 1955, and used it accordingly for years after.

The Church Street business corridor itself and bordering neighborhoods fell into major decay, which was emblematic of what was happening to once thriving black neighborhoods throughout the country—not just in the south, but particularly so, due to the dictates of integration. Thankfully though, in 1982, the Attucks was added to the National Register of Historic Places.

“When I first came to Norfolk, Church Street was a very active street with lots of black businesses…” says the Reverend Joseph N. Green, Jr., who served on Norfolk’s city council for 20 years, with ten of those years as vice-mayor. “And then they were all gone, for the most part, and I was looking around to see what we could save.”

Thanks in large part to Father Green’s many efforts, along with Denise’s full-time work as project manager for the renovation campaign, 8.3 million was raised to restore, renovate and re-open the Attucks Theatre. The renovation took 3 years.

“We broke ground in September of 2001, and then we had the grand opening in October of 2004,” says Denise. “Once it all came together, and we had the grand opening, it was just extremely exciting and gratifying that all of that hard work had been for a great cause, and came to fruition.”

Father Green tells me later that evening, “of all the things that I’ve done, while I was on the city council, the Attucks is the project that I’m most proud of.”

The new Attucks Theatre, which officially opened in October 2004, was christened by a concert performance of the Preservation Hall Jazz Band, from New Orleans. Since then, the gorgeously restored venue—with its 624-seat capacity in its performance hall, including 24 box seats, a green room, dressing and meeting rooms—has played host to numerous high profile concerts and theatrical productions, including Audra McDonald, dance company Urban Bush Women, and the MLK play, The Mountaintop. The venue is owned by the City of Norfolk, and managed by SevenVenues.

Hampton Roads native Vincent Gardner, a trombonist and composer with the Jazz at Lincoln Center Orchestra, which is led by Wynton Marsalis, played the Attucks back in 2015 as a member of the esteemed jazz orchestra. “I was very proud to play there when I finally got there, and was able to get into it, and feel what the space felt like,” he says by phone, a couple days later. “Older theatres are my favorite places to play.”

That same day I’m called by Jasmine Guy, who brought her excellent Harlem Renaissance production, Raisin’ Cane, to a packed house at the Attucks on April 11th, 2014. Jasmine is best known for playing Whitley Gilbert on A Different World, The Cosby Show spin-off, which lasted for six seasons on NBC. I adored both shows―and Whitley, a black southern belle from Virginia, is one of my favorite TV characters of all time. Jasmine has since gone on to star in popular TV shows like The Vampire Diaries and K.C. Undercover, as well as numerous roles on stage, and in film.

“I remember how beautiful the theatre was,” she says. “And I love old theatres that are renovated as opposed to spanking, brand new facilities which are just a little colder and uniform.” During our conversation we also chat about the Harlem Renaissance, and the Governor Northam controversy, which is still ongoing. “It is evident and clear that people don’t know the history of minstrel shows, and the history of blackface.”

We move on quickly from that though, and Jasmine expounds on why theatres like the Attucks are still important to the culture. “I think theatres like the Attucks, because of their size―they were built for intimacy―are great ways to educate and to introduce people to live theatre…” she says.

“The Attucks is a part of a community, and it brings that legacy― by standing there. And it needs to continue to stand. I’m so glad they renovated that space. It’s such a theatre of pride for the community―for everyone in the community.”