Ubuhle Women: Beadwork and the Art of Independence.

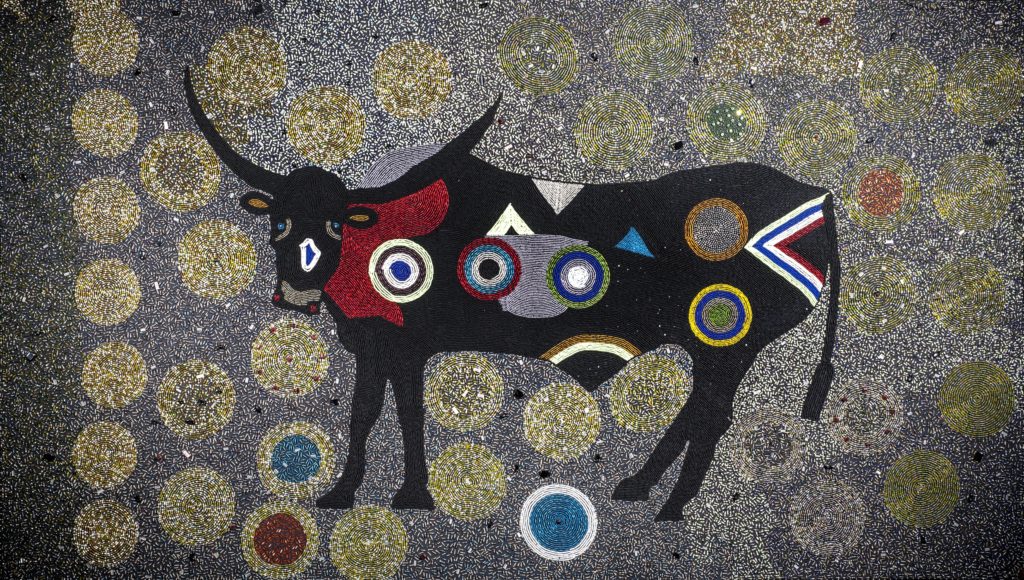

Bongiswa Ntobela (South African, 1973?2009)

Funky Bull, 2006

Glass beads sewn onto fabric

The Ubuhle Private Collection

By Betsy DiJulio

This is the story of how thread—and beads—became a lifeline.

In 1999, Ntombephi “Induna” Ntobela and Bev Gibson, the former with a traditional education and the latter with a self-described Western education, formed the Ubuhle (oo-buk-lay) collective on a former sugar plantation that they call “Little Farm” in South Africa. There, Zulu and Xhosa women from the Eastern Cape and KwaZulu-Natal provinces parlayed a generations-old bead art tradition into a contemporary expression called ndwango or “cloth” and created a market for it. Ubuhle means “beauty” and indeed, both the spirit of these women and their artistic output is beautiful.

Male flight from country to city in search of cash salaries caused traditional agrarian social systems to erode, including the breakdown of family life. Through the commercialization of ndwango, the Ubuhle community provided local women artists with a private income stream and a route to financial independence.

Far from commercial in appearance these intricately beaded ndwango—glass Czech beads stitched onto black fabric that shimmer like water—are instead quite spiritual in nature. Many serve as memorials—since 2006, the Ubuhle community has lost five, or nearly half, of its artists to HIV/AIDS and other illnesses—and, as such, provide a form of therapy to the surviving six makers.

Gods, gardens, heaven, and earth pervade the ndwangos. Trees figure especially prominently in the textile motifs. Trees are rooted; and they reach. Archetypally, they have been significant to many cultures. In one panel, a peach tree is a memorial to the artist’s impoverished mother who used to take her sewing machine out under their peach tree to work beneath the branches ablaze with blossoms in spring. In another, flowering cherry trees are associated with Little Farm. In the work of Zandile Ntobela, the cherry blossom has become disassociated from the tree and appears in all of her ndwangos as a decorative pattern.

Another common subject is cattle; bulls are a traditional form of wealth in South Africa and help form the economic basis of traditional Xhosa and Zulu society. The animals’ bold shapes and handsome patterns represent one artist’s grandmother, another’s father, and a reference to the Zulu king.

The exhibition begins in the glass gallery, continues with two pieces at the top of the stairs off Huber court, and concludes with the monumental “African Crucifixion,” in the Baroque galleries. This tour de force was commissioned by the Anglican Cathedral in Pietermaritzburg, the capital of the KwaZulu-Natal province. A nearly year-long collaboration by seven Ubuhle artists was driven by Induna’s suggestion of trees as a lens through which to consider and tell the Biblical narrative. Working together, the women generated the idea for a “Tree of Destruction” to embody Jesus’s suffering, while the “Tree of Life” embodied his resurrection. The crucifixion itself was conceived as the “Tree of Sacrifice.”

A 15-minute video accompanies the exhibition and, though technically seamless, it leaves narrative holes. Still it is worth the time it takes to watch for context. But it is a statement by Carolyn Swan Needell, Ph.D., the Chrysler’s Carolyn and Richard Barry Curator of Glass, that provides the most powerful summary of this work’s significance for the artists, “Each ndwango is a site of deep personal meaning for the artists—a place to dream, a place to mourn, and above all, a place to remember.”

This exhibition was developed by the Smithsonian Anacostia Community Museum, Washington, D.C., in cooperation with curators Bev Gibson, James Green, and Ubuhle Beads, and is organized for tour by International Arts and Artists, Washington, D.C.

WANT TO SEE?

Ubuhle Women: Beadwork and the Art of Independence

Through February 24

Chrysler Museum of Art