Earl Swift takes up residence on Tangier Island—again—for new book

By Jim Roberts

Earl Swift first visited Tangier, the 1.2 square mile island in the Chesapeake Bay, in 1999. The concept of global warming was just an ember compared to the firestorm it is today, but he saw the effects of climate change first-hand.

“It was pretty clear that nature was taking aim at the place in a pretty steady fashion—a pretty relentless fashion,” the author said during a recent interview with Veer Magazine. “I grew very attached to Tangier during that stay. It’s difficult not to. It’s a place that gets into your pores.

“Over the years that followed,” he continued, “I lived on the Lafayette River in two different places, and it seemed that with each storm—and it really didn’t even matter how severe the storm was—that the water would come up higher. … It got me thinking: Gee, if it’s this bad in Norfolk, it’s got to be exponentially worse on Tangier. So I kind of put it in the back of my mind that I needed to get back out there and to revisit.”

Swift has since relocated to the higher and drier clime of central Virginia—living first in Charlottesville and, for the last three years, in Crozet—but he decided to go back to Tangier late in 2016—just as he was finishing his last book, “Auto Biography.” At the same time, a Scientific Reports study revealed that the island had lost two-thirds of its area since 1850.

“The view was alarming,” Swift said. “When that report came out, that just seemed to underline the thinking that I was already doing about the story. Nine days later, I was on the island. … I showed up on Christmas Eve for a reconnaissance trip. I made another reconnaissance trip in February of 2016 and then moved to the island and established residency in May of 2016.”

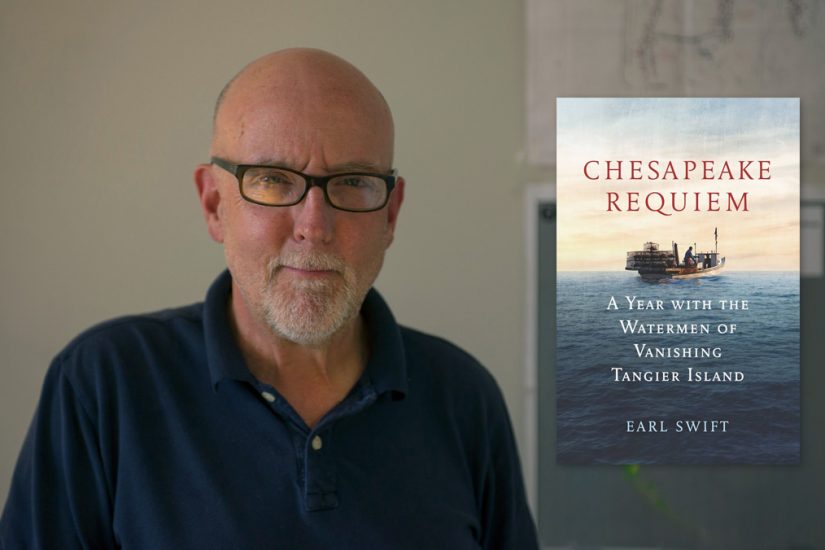

The result of that stay is “Chesapeake Requiem: A Year With The Watermen Of Vanishing Tangier Island.”

“It’s a book about climate change on the one hand,” Swift said, “but really it’s a book about where we’re going if we don’t take heroic measures to save it. … It’s going to be most likely the first place that we lose to climate change. People need to know what it is that we’re going to lose because we’re going to lose something really special if we lose Tangier.”

With the exception of the long-form feature stories Swift wrote for The Virginian-Pilot back in 2000, “Chesapeake Requiem” is unlike anything else that’s ever been written about Tangier. The key was his long-term residency.

“Most tourists show up just before noon or just after on a tour boat, and they get back on a tour boat mid-afternoon to go back to the mainland,” he said. “They have three, four hours on the island. That’s enough time to take a golf cart tour of the place, narrated by an islander. It’s time to have a meal in one of the five restaurants—four of which are open only in the summer. And it’s time to buy a souvenir or two. You know: a Tangier ball cap and a T-shirt. But it doesn’t give you a lot of time to really absorb the culture of the place.”

Even journalists’ visits are stereotypically short. “For 100 years, Tangiermen have had reporters visiting them,” Swift said. “They’ve gotten accustomed to most of them showing up, spending a day or two and then leaving again. Consequently, the stories that have been done about Tangier over the years have a certain sameness about them.”

Swift differentiated himself not only by renting a room on the island and staying for 12 months, but by fully integrating himself into island life. That meant going to church and town meetings with its 400-some residents and even working on some of its renowned crabbing boats.

“This book really was the product of relationships,” he said. “I was fortunate enough to be accepted by the islanders and to be embraced by them and to become part of island life for however brief a time—to pretend I was a Tangierman. Playing fly on the wall depends on people trusting you. I hope I repaid that trust. My energies were directed toward capturing the island—its micro history, its micro character—as accurately as I could.”

He said he knew even before he showed up on the island that he had a compelling story. “You’ve got to really put yourself into it, but if you do your due diligence, if you do your homework, the situation was such that I would have had to mess up pretty badly not to get a story of some sort out of it. It might not have been this book, but a compelling story.”

In June—two months before “Chesapeake Requiem” was released—Outside magazine published “The Incredible True Story of the Henrietta C.,” Swift’s 8,000-word feature about a crabbing boat that was lost off Tangier Island in April 2017.

Jason Charnock, the captain’s mate, was rescued, Swift said, “only because virtually every able-bodied man on the island jumped in their little boats and headed out into a storm that had already claimed—for all they knew—one of the most experienced captains around.”

The captain—who didn’t survive—was Charnock’s father.

“That incident just defines Tangier for me,” Swift said. “The idea that these guys would drop what they were doing—without a second’s hesitation—put themselves into harm’s way. I mean in serious harm’s way. The waves that day were nuts. Tangiermen said afterward they had never been in water that was acting the way that water was acting. It was confused and anarchic.”

The Outside story is not a straight excerpt from the book, but the timing of the two projects allowed for some creative cross-over. “When I got the manuscript back after the editors had gone through it the first couple of times, I substituted pieces from the original with pieces from the magazine,” Swift said. “Actually, you could argue that Chapter 22 of the book is almost an excerpt of the magazine piece. Chapter 22 of the book does cover the same ground in different styles. It’s got a different feel to it.”

“Chesapeake Requiem” was just released on Aug. 7, but it has already received bushels of critical praise. Jack E. Davis, the author of “The Gulf: The Making of an American Sea,” wrote: “Earl Swift is as much a master of crafting words on the page as capturing the instructive voices on this shrinking Chesapeake island. He has written not a farewell but a commencement, not an insular but a universal story, one we all should know, of challenge, forbearance and possibilities.”

Swift said it was a thrill to get the blurb from Davis, a 2018 Pulitzer Prize winner. “I was in the process of reading his book when he blurbed it,” he said. “I had no right to expect that he’d blurb it at all. And to get Bill McKibben? Good golly. That guy’s a rock star of environmental writing. I was super excited about that.”

So what’s next for Swift?

“I am concentrating on spending 2018 not writing a book,” he said. “It’s the first time in 12 years that I have not been writing one—or not been working on one in some regard. I’ve resolved to myself that I would spend a year doing magazine work. … So far, it’s worked out OK.

“The beauty of writing for magazines,” he said, “is that I can see the conclusion of the project right from the very beginning, and with a book you can’t. It’s so far off—just so distant. Writing a magazine piece is like climbing the Half Dome at Yosemite. And writing a book is like having to build base camps and all that in preparation to climb Everest.”

To extend Swift’s analogy, one could say he solo summited with “Chesapeake Requiem.” But there’s a catch: He knows how his book ends, but no one knows when—or how—Tangier’s story will end.

“I don’t know,” he said, taking a long pause. “I don’t think anyone on the island has thought that far ahead.”

For more information about Earl Swift and his books, visit: www.earlswift.com