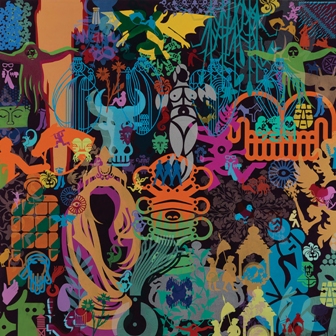

Ryan McGinness, Art History Is Not Linear (VMFA) 6, 2010, Acrylic on panels. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond. National Endowment for the Arts Fund for American Art. © 2014 Ryan McGinness / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

By Betsy DiJulio

“Ryan McGinness: Studio Visit” is a uniquely seductive concept for an exhibition, as visitors are made to feel as though we are walking through his studio space. Organized by the VA Museum of Fine Arts in Richmond, MOCA’s installation of the components makes it work beautifully.

McGinness, a native son of Virginia Beach who road is skateboard—figuratively speaking—to the big time, now works as a highly sought-after artist from his beautiful and meticulously-organized NYC studio. In the gallery, two wall-size photographs of his scrupulously-arranged materials and supplies provide a backdrop for work tables that appear as though the artist has just stepped away mid-project.

Immediately adjacent, a conversational grouping of three tomato-red contemporary sofas and a pair of low coffee tables—on which McGinness’s books like Flatnessisgod are arranged and exhibition invitations and professional correspondence are visible under the glass tops—invite viewers to sit down and watch a large-screen video of the artist working with his studio assistants. The video is a bit slow and monotonous; you know, like real life.

Elsewhere is installed a timeline of McGinness’s work beginning in childhood and continuing through “Chart of World Art,” a piece many feet in length that he created on lined notebook paper in response to a class assignment while a freshman at Carnegie Mellon University in Pittsburgh.

The rest of the exhibition is devoted to the work for which McGinness is best known: several of his exuberantly-colored, hyper-layered and overlapped, “icon”-driven acrylic-on-panel screenprints, each one containing hundreds of individual images; an embossing and a series of black-and-white cyanotypes with not only the color, but the layering and overlapping, turned way down; and several mini-installations that document the artist’s creative process by which an object is transformed into a flattened, simplified, and silhouetted logo-like iconic representation. The end-result may be simplified, but the process is anything but. For each and every icon, a systematic progression of gradually morphed and tightened hand drawn images is ultimately refined as a computer vector drawing.

As a teen, unable to afford the highly brand and logo-intensive skate decks and t-shirts that were—and are—all the rage, but from a family that encouraged creativity, McGinness began making his own versions which his friends coveted. This experience coupled with formal art training in college and knowledge of the work of the early 20th C. German artist, Gerd Arntz, a “Cologne Progressive” who set about to create an easily recognizable system of symbols, fed into the evolution of McGinness’s highly individual and recognizable visual language.

Lest McGinness’s work appear one-dimensional—no pun intended—from the particular pieces selected for inclusion in “Studio Visit,” a quick trip to his website (www.ryanmcginness.com) will dispel any such notion. What is revealed there is that McGinness possesses extraordinary clarity of vision coupled with an immense capacity for the transformation of interior spaces.

Not only does he manipulate the work itself—the color harmonies; the iconography of geometric shapes and sweeping calligraphic flourishes; and the visual and conceptual interactions of the imagery within each piece—but the ways in which the individual pieces are installed. Working flatly, McGinness nonetheless shapes three-dimensional space, creating striking rhythms and changing emphases in ways that are stylish, visually exciting, and complex, yet ordered.

New Waves 2015

Now in its 20th year, MOCA’s “New Waves 2015”—though not without its standouts—was, overall, somewhat underwhelming. From some 2,000 entries, juror Lisa Dent, director of Resources and Awards Programs for Creative Capital, chose 26 pieces by 22 artists.

Beautifully installed, as always, the show nonetheless suffers from a number of works that appear sophomoric. This perspective was confirmed when a fellow visitor was overheard mentioning that she had made a piece similar to one of those on exhibit when she was a freshman in art school. Still other pieces seem to be based on more individual concepts, though awkwardly realized.

That said, there are some stellar works, not least among which is 15 year old artist and scientist, Michelle Marquez, and collaborator, Patrick Gregory’s, 2014 video “The Emotional Dimensions of the James River.” This ambitious and beautifully otherworldly film is, alone, worth the price of admission.

Nearby, 48 bronze castings comprise Erika Diamond’s “Handshake Collection (A Year in Richmond),” from 2013. Together, these “personal fossils” create an “ongoing catalog of the people in my life,” according to Diamond, for they are the impression left in a malleable material when she shook hands with people she met during her first year in Richmond. Again, the same visitor provided insightful commentary, calling the castings “the spaces between.”

A very different take on hands touching, Catherine Day’s “Absence: Hands, Lifting Up” also from 2013, is a poignant and ephemeral photographic image of the artist touching her father’s hand on his deathbed. Printed on several suspended layers of filmy, translucent black fabric, it seems, ironically, to bring to life the phrase “beyond the veil.”

Throughout, photography is exceptional, notably, Shannon Lee Castleman’s, “Cotton Candy Bike, Hanoi, Vietnam;” Sam Hughes’ “36°54’52″N_75°59’34″W;” Howard Rodman’s “No TV Necessary;” Peter Toth’s, “Dugout in Fog-Nepal;” and Andrew Watson’s, “Rust and Bone,” 2014 (a dye sublimation print of a hand-built diorama). Though each piece is dramatically different from the others, there is about all of these pieces a kind of visual lushness imbued with a vaguely discordant undercurrent.

Ryan McGinness: Studio Visit and “New Waves 2015”

Through April 19

Virginia MOCA