By Jeff Maisey

The proof is in the shot.

Sometimes one single image captures the heart and soul not only of the viewer, but of the subject itself.

Often such images happen by chance — being in the right place at the right time.

The photographer must always be at the ready. For two or three fleeting seconds an opportunity presents itself, and then it is gone.

Norfolk photographer Mark Atkinson seems to have captured people from India and Haiti to Virginia in the most serendipitous of moments, snapping iconic works of art as intriguing as masterpiece paintings hanging on the walls of galleries worldwide.

As a commercial picture-taker, Atkinson’s true skill as a portrait photographer is evident.

The shutterbug’s “greatest hits” will be displayed April 13 through July 22 at the Hermitage Museum in an exhibit titled “Proof: The Retrospective of Photographer Mark Edward Atkinson.”

Atkinson describes the exhibition of work spanning over 30 years a “memoir of images.” His images have appeared in publications ranging from The New York Times and Newsweek to the National Enquirer.

Before moving to Norfolk in the 1980s and ultimately opening the award-winning agency Otto Design + Marketing, in 2000, Atkinson worked first as a journalist at Raleigh, North Carolina’s daily paper, News & Observer.

Atkinson’s body of work certainly tells a story, just like the man himself in this following interview.

Can you share with us the thought process of making this exhibit a retrospective of your career as a photographer?

The Hermitage invited us to do a show about a year and a half ago. We love the space and the surroundings. I’ve shot over there on a number of occasions.

As the thinking evolved for putting together a show the people I work with said if we are going to go through the trouble of doing one let’s do a retrospective. Let’s look back from when we started to today, and try and get a mix of images that reflect a body of work, and also tell a story about starting here and going there.

We also — in the process of it — realized the Hermitage space — because it’s a house — we decided the stuff that we can’t put in the show we’ll turn into a book. Concurrently, while working on the show, we designed a book that’s 328 pages — a coffee table book. It’s nice to have both at the same time.

If you would take a moment to self-analyze, overall, how would you say your approach and technique to photography evolved over the past 30 years? I’m sure you don’t use film as much these days.

I finished school around 1980. Everything was film up to 2000. It was a different game.

I loved shooting film. I loved a lot of thing about it. We thought of ourselves as great black and white printers, and really kind of honed that as a craft.

Once digital came it was good and is becoming much better.

I don’t miss standing in darkrooms with trays of chemicals. I think the opportunity to really hone your craft and play with images…it has never been a better time in this craft than now.

Is it easier to be a photographer? I tell people it’s harder. It’s easy to get into, but it’s also a very competitive field because everybody’s in it now.

I see some of the most beautiful iPhone and phone pictures that you can imagine. Every time I look at all the social media stuff, I go, “Wow, that is really killer.”

It has allowed people to explore and do great imagery. On the professional side with people like myself it kind of pushed people to make sure you’re upping your game. So that’s been inspiring as well.

It’s changed quite a bit. I’m happy I lived through both of those periods.

Do you think it’s more challenging now for college art students seeking to make a career in photography after graduating now that digital photography has made things easy for those who would not otherwise produce good work?

The short answer would be, yes, I do.

The cameras are so good now in terms of exposures and focus. The things we struggled with in the film days when you had to make sure your exposures were on the money and that you were not going to see your results until your film was developed, it separated people a little bit. It was more daunting for folks wanting to get into it.

Well, it’s not now.

Even if you’re using auto focus and automatic exposure, you’re going to get a good picture nine times out of ten. So, it’s easy to get into and it makes it more challenging to go out and make a career of it. You really have to establish yourself. I’ve got to be willing to work really hard. You’ve got to be a smart business person. You’ve got to promote. You’ve got all these things that go along with separating yourself from the crowd that don’t necessarily have anything to do with photography that are going to be more and more important.

I grew up in the newspaper business. I started as a writer for the Raleigh paper and then I was a photographer for the News & Observer in Raleigh. I have a great journalistic fascination.

If you look at what’s happened at The Pilot (Virginian-Pilot) with the shrinking photo staff, they’re asking Pilot photographers to shoot video at the same time. They shoot stills. They shoot drone work. You’re really having to multitask in a way you never did before. It’s a much more competitive and demanding field to get into.

Consequently, day rates for commercial photographers have dropped dramatically.

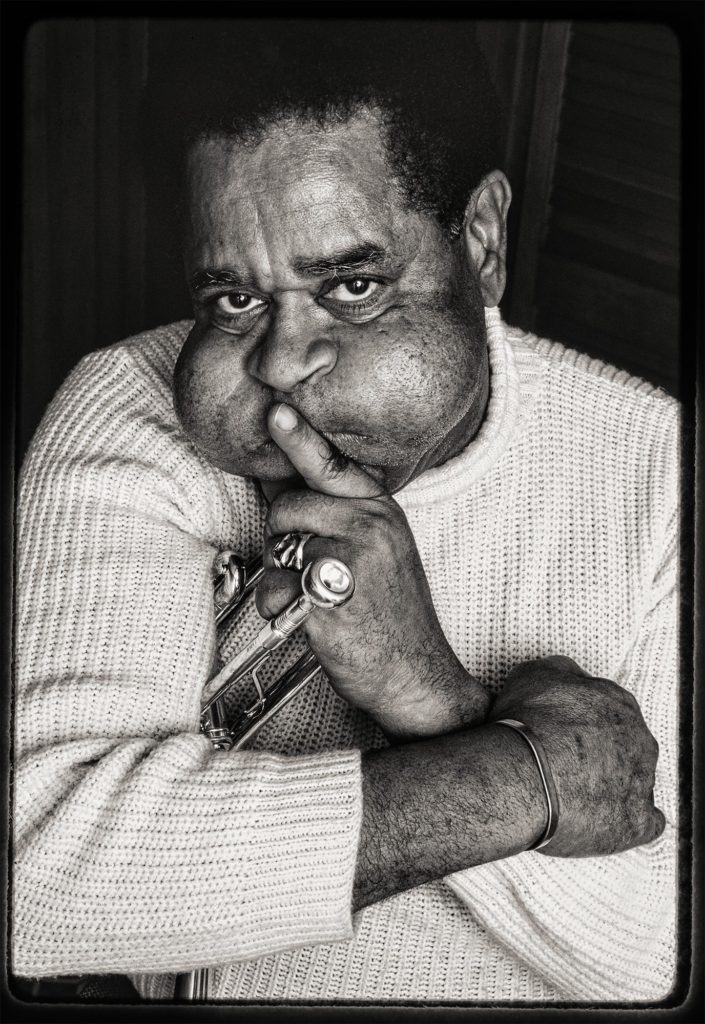

Let’s talk about some of your captivating work in the exhibit. One is a great, tight portrait of jazz legend Dizzy Gillespie. How did you get that photo shoot and what was it like to work with such a master artist himself?

I shot Dizzy in the mid-‘80s for a magazine out of North Carolina. I shot him in Brooklyn at his house on a Saturday. He was one of the nicest guys I’ve ever met. We played pool in his basement. His wife was there. It was just very down home, very sweet.

The day before I shot Martina Navratilova at Flushing Meadows at the US Open. She was a complete diva. She was just rude. She kept me waiting.

I finally had to say to her and her people, “You know, you could have said no three days ago. I flew up here. You agreed to this. You’ve kept me waiting for four hours. We’re either going to do this or we’re not.”

I went from that experience thinking, “wow, this is how famous people act” to spending the afternoon with Dizzy and playing pool with him.

We ended up shooting our cover shot in his laundry room.

In terms of lighting and aperture, when shooting film, were there tricks of the trade and adjustments for shooting portraits of people with different skin tones and hues?

You know I used to have colleagues say if you’re shooting an African American person you’ll need to open (aperture) up a little bit.

To me your skin tone is your skin tone. If it’s darker or lighter, you shoot to that as long as you got detail in it. That’s what you wanted to have.

We’ve shot Pharrell as well. Pharrell’s skin tone and his (Dizzy’s) are obviously very different.

I’ve shot people who were pale as can be.

To me it was different in the film days because we were shooting transparency film, like color slides and things like that. It didn’t have the latitude that digital has today. It’s much more forgiving.

Can you contrast your portrait with Dizzy to the one of Pharrell Williams sitting on a stairway?

The difference between Dizzy and Pharrell…let’s start with the fact that it was the ‘80s (when shooting Dizzy). Nobody had cell phones or social media. People weren’t online.

We had to setup things in advance. It wasn’t like he (Dizzy) was at a point in his career where he was checking his social media or had any handlers. There were no interruptions or things like that.

With Pharrell, he was camped out at a hotel on an awards weekend in LA. He had been in this place for, like, a month, he said. He had come off a night before that was kind of late.

We were supposed to be able to shoot him at noon for an hour. By 12:45, he still hadn’t showed up in the lobby.

He came down at ten ’til one and was a little lacking in sleep, shall we say.

We shot a couple things in this spot at the hotel where I had picked out. Then we moved to this bar at the hotel. All the time he was getting texts from folks saying we’ve got to move on. He had a handler with him.

As he was leaving, he said, “We’ve got to walk back here and get the car.”

There was this staircase leading up to the parking deck across the street from the hotel. I said, “Let’s just sit here for a second before we get out of here.”

So literally the last two or three minutes of the shoot took place there on his way to get the car.

The whole shoot was probably 20 minutes.

You do a lot of travel and work while on the road. Can you give us some insight into the photo titled “Ganja”? How did you come across this guy and then photograph him?

I shot that in Varanasi, India. It’s a holy city on the Ganges.

When you go down to the water there there’re all these holy men. They gather there. They paint their bodies up and smoke.

I went down there at sunrise a couple of mornings. I got this one image that was kind of iconic. We’ve used it to help promote the show quite a bit because it’s colorful and interesting.

It’s definitely a fascinating place.

(Girl at the Red Doors, Port-au-Prince, Haiti, 2015)

There’s another image you shot on your travels. The one of two giant red doors with a little girl looking out through the narrow opening. How did that moment come about that you captured so well?

That’s in Haiti. It was a couple of years ago.

I took my son, Walker, with me. He’s 22, and for a couple of years he said, “Dad, when are you going to take me on one of these trips?”

I wanted him to be old enough to where he could travel and be responsible because most of the places I went to weren’t always the safest of places. And it only got worse in the last decade.

So, I took him to Haiti.

This was one morning where we were walking from one place to another. I always like to be out early in the mornings or late in the evenings when the light is better.

We passed this door and as we were passing all of a sudden this little girl was there peeking out.

I shot a couple pictures with my real camera. I shot a couple iPhone pictures.

I couldn’t have staged the cuteness of this girl and the little dress she was wearing, and the red doors.

I tell people who ask me how do you get good pictures that part of it is just showing up. Part of it being present and going out every day. You’re not going to get great stuff if you stay at home.

It was good for Walker to see, because all of a sudden there it is in front of us and we’re getting this iconic image that I love.

He said, “Well, there’s no science to this, dad.”

You shared a great story about the Dizzy Gillespie shoot. Is there any other sort of best experience you’ve had as a photographer?

I’ll tell you an interesting story.

Years ago, in the early ‘80s, I was doing a story for Commonwealth Magazine on Private Is (private investigators).

I had three or four people I shot for this story. It ran. A couple years go by and I’m down in Florida shooting sailboats.

This TV programming stopped for a news alert. Basically, they were reporting the FBI arrested this guy in Washington who was passing off secrets to the Russians. It was Johnny Walker.

Sure enough, I get a call from The Virginian-Pilot saying, “We understand you shot this picture of Johnny Walker and we were wondering if we could use it.”

The picture of Johnny Walker is him at a conference table with all this electronic eavesdropping equipment in front of him that he used.

I said, “Sure, you can use it this one time, but you can’t put it on the wires.”

The great thing about it was they took him up to Baltimore; they locked him up in jail; the jail was connected to the courthouse.

I had the image that made him look like a spy.

I tell people I stopped working for the rest of the summer and just answered the phone. We sold that image for two or three months to everybody worldwide.

I became very adept at understanding how much things would sell for and how to base your pricing. It remains today the biggest selling photograph we ever made — Johnny Walker, a criminal.

We cannot throw out all these files now because we never know who’s going to turn out to be a criminal.

WANT TO SEE?

“Proof: The Retrospective of Photographer Mark Edward Atkinson”

April 13 through July 22

Hermitage Museum & Gardens