By Montague Gammon III

Once upon a time – and a very bad time it was too, to be male, alone and Black, and subject to Southern Police scrutiny – novelist John Ball picked up a Mystery Writers of America Edgar Award for Best First Novel with In the Heat of the Night, his 1965 whodunit about what happens when Pasadena’s ace homicide detective Virgil Tibbs, an African-American, passes through the small South Carolina town of Wells just as a prominent White musician and music promoter is murdered.

Found waiting for a departing train at the town’s railway station with substantial cash on hand, Tibbs is arrested. (Surprise surprise!)

Hollywood turned Pasadena, CA into Philadephia, Pa; Wells, SC into Sparta, MS; and the musician into a manufacturing entrepreneur for the 1967 film. Sidney Poitier played Tibbs, Rod Steiger played racially prejudiced local police chief Bill Gillespie, and the movie, about how Tibbs and Gillespie reluctantly teamed up to solve the murder, won 5 Oscars, 3 Golden Globe Awards, and a whole passel of others.

The flick is coming to the Roper Theatre in Downtown Norfolk for a matinee showing February 15 – and as a recognized classic its arrival is most welcome – but the bigger news is the unique stage production that will visit the Roper for one evening show Feb. 20.

When the L.A. Theatre Works, which specializes in what they call “ ‘live-in-performance’ radio drama” decided about a year and a half ago to do a stage production, “Who knew,” said their Producing Director Susan Albert Loewenberg, that events like the Ferguson shooting would re-focus America’s attention on lingering racism.

Though the novel was regarded as a murder mystery, the emphasis is now on the relationship that develops between the two police professionals, neither of whom is eager to work with the other.

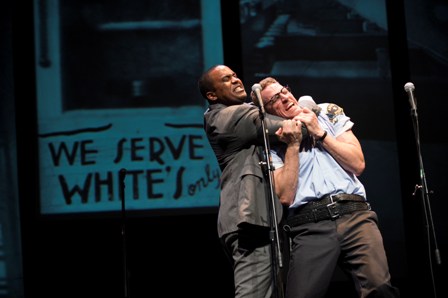

The topicality of the piece sort of jumps out at one; the uncommon approach to staging, in which the actors use big (old fashioned) stand up microphones as if recording a radio broadcast, and interact little with each other but essentially address the audience directly, will be both unfamiliar and, it seems, especially interesting.

There is a backdrop on which slides –”scenes of the town and more abstract [images] … to set the locale,” says Lowenberg – are projected, and microphones are placed in various areas of the stage to allow for some movement of the performers.

The staged “radio drama” productions use a combination of recorded sound effects and sound effects generated by the actors.

“People love watching the sound effect,” Ms. Lowenberg says, a statement which, when examined, makes the point of how very unlike any other sort of live performance “live radio drama” really is. It’s like saying “here are the effects,” she explains.

Audiences come “with no expectations,” Ms. Lowenberg says.

James Morrison, who plays racially prejudiced Chief Gillespie in the production, describes the staging as one in which “We have invited ourselves into your laps.”

“In radio [the actors] cannot hide,” she notes.

“The strength of our production is the best example of the ritualistic theater experience, where [the performers] are actually saying to the audience you are part of the equation; you play as much a part of this as we do. We would not exist without you,” he continues.

Stripping away the usual trappings of conventional stage performance, leaving the actors to convey characterization and action almost wholly with their voices, “focuses [the audience member’s] mind,” Ms. Lowenberg notes. “Makes them part of the though process,” of the performances, Morrison adds.

Both producer and actor have plenty to say about the timeliness of In the Heat of the Night’s reappearance, about how racism is America may be less open than it was when the book and movie appeared but that it is part of “the DNA” of the country.

There’s a Question and Answer period after each performance, and Lowenberg says that more than a few times people have echoed the remarks of a man who said that he had once been “one of the people in this play,” that is, the unthinking prejudiced, and that “watching this play brought that back home” to him.

It should be mentioned that the script does not pull any punches about using rough language, including the infamous “N word,” but as Morrison notes, that is the only appropriate to the context of the original work.

In the Heat of the Night

Roper Performing Arts Center (TCC)

Los Angeles Theatre Works performance

Feb. 20, 8:00 p.m., followed by a Q&A

Film: Feb. 15, 3:00 p.m., followed by a panel discussion

757-822-1450